The new Fourth Edition with 44-page Index

Joining the War at Sea 1939-1945

- Draftees or Volunteers

- U.S. Military Draft and Pearl Harbor

- Warship Building

- World War 2 U-Boat

- Collision at Sea

- Operation Torch

- Sea-based SG Radar

- Attack Transports Sink

- Assault Landing

- Tiger Tank

- Darby Rangers Setback

- Eisenhower Needed Seaports

- Rohna Sinks; 1000 Soldiers Perish

- Death, Survival, and Leyte Gulf

Rohna Tragedy Tops Transport, Destroyer Toll

300 warships/transports in "Joining the War at Sea" listed alphabetically

Tiger Tanks at Salerno, Italy, in World War II

German tanks duel U.S. warships at Salerno in direct fire. 88mm supersonic gun fails to match Navy ships' rate of fire

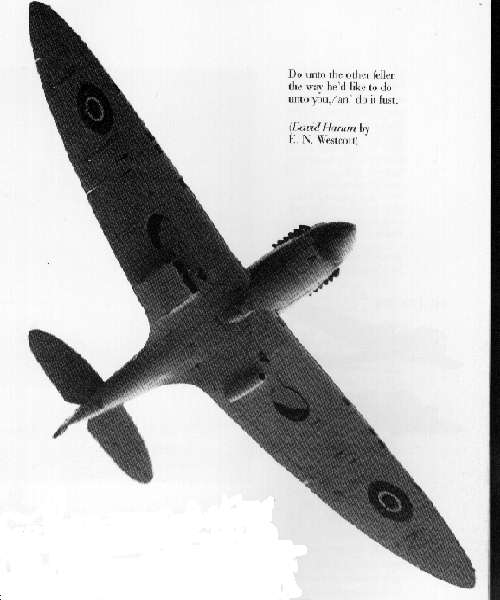

Spitfire was our only high altitude cover at Salerno where Luftwaffe used remote control standoff weapons extensively.

Copyright 2012 Franklyn E. Dailey Jr.

Part I - Allied Strength Up; Strategy in the Mediterranean War at Turning Point

When A Destroyer's Ammo Is Expended

I need to cover just one detail on the subject of ammunition available. The cruisers and the battleships routinely reported the number of rounds expended as part of their daily reports. Occasionally, my destroyer, the USS Edison DD-439 made an ammo report when queried by the Squadron commander or other higher authority. But Edison did not routinely make ammo reports. We looked in the magazines after a concentrated firing period and, eye-balling the space, estimated the rounds fired since the last "inventory". When appropriate, we made it a point to tell the skipper that we did or did not need ammo. He was, therefore, always informed as to the essentials and included an ammunition report to higher authority when relevant. We just did not routinely report the "score" on ammo as was the established practice with fuel. Ammo in reserve became a more important factor in these next three action campaigns of the USS Edison, Salerno, Anzio, and Southern France. At Salerno, the ammo level dictated passage through that narrow channel between life and death for one U.S. destroyer!

Contested Priorities

Salerno was another step in the strategy to penetrate the soft underbelly of Europe. The U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) increasingly wanted to give its priority to a cross channel invasion of western Europe. Prime Minister Churchill wanted to demonstrate the vulnerability any defender of Central Europe would have in attacks from the south, originating from Italy eastward. He had taken this route in WW I campaigns and though defeated then, anticipated that the WW II Allies could accomplish decisive war objectives with the appropriate disposition of Mediterranean-based forces.

Prime Minister Churchill was not opposed to the cross channel invasion but it was not a 1943 priority for him. Increasingly, U.S. commanders got the impression that it might not even be a 1944 priority for the PM. Moving up the Italian peninsula, therefore, fit Churchill's idea of the strategy that should be employed. Interestingly, the Southern France invasion of August 1944 found the U.S. and England switching sides on the importance of the Mediterranean. The south of France did not fit Churchill's soft underbelly focus but it did fit the U.S. concept of leverage once the cross channel invasion of France had begun.

Trident and Quadrant

There were two conferences subsequent to the Casablanca Conference that dealt with Mediterranean matters. The first was the Trident Conference and it took place 12 May 1943 in Washington DC. It got off to a good start with word of the Axis surrender in Tunisia. The U-boat picture in the Atlantic had eased somewhat. The Germans on the eastern front had retreated under Russian pressure to the Donetz River basin. The U.S. was about to step up the war against the Japanese in the Solomons. While all the highest level people who attended the Casablanca conference were present at Trident, neither General Eisenhower nor any of the other field commanders could come. Weary from fighting in North Africa, the active force commanders were attempting to meld their field experience into HUSKY (Sicily) plans.

Churchill's persistence won the immediate argument and an invasion of Italy went into planning. Landings at the Gulf (or Bay, as it was often referred to) of Salerno, Italy, just below Naples, would be the target. It was authorized officially on 26 July 1943. The Quadrant Conference in Quebec in August 1943 confirmed the decision. The operation's code name was to be AVALANCHE. What would happen after Salerno was not determined.

Salerno; More Than A Combat Landing Operation

Although the U.S. subscribed to the Salerno decision, and later to what became the Anzio siege (it was not supposed to be a siege), key commanders and key invasion forces at Division strength began to show up on lists to go to England and make ready for the Normandy operation. One who was an early nominee for such a move was British General Montgomery. Another important move in the offing was a change in General Eisenhower's responsibilities. When the British General Alexander took over overall command of ground forces on the Italian peninsula and General Mark Clark was successfully ashore as commander of the U.S. Fifth Army in Italy, the command structure in the Mediterranean sector changed. "Ike's" dual role, for active prosecution of the Mediterranean effort and for the planning and build up effort for Normandy, ceased. He would become actively and continuously dedicated to preparations for the cross channel invasion.

Insofar as Italy was concerned, after Salerno, Ike became a negotiator for talents there that he felt he needed in England. For Salerno, however, Ike was a negotiator for larger forces for that operation as he was still the senior military commander with operational responsibility in the Mediterranean. The U.S. Army First, Third, Ninth, 45th and Second Armored Divisions had already acquired valuable experience and after Sicily, some got a rest. The U.S. 36th Division was to get its baptism in the Salerno assault operation with the U.S. 45th Division in immediate reserve.

Salerno was a pivot, militarily and strategically. Salerno was the last Mediterranean operation where the soft underbelly strategy edged out the cross channel in priority. Casablanca, Sicily and Salerno were a phase; Salerno and Anzio were a phase. But at their common juncture, Salerno, the important force and command changes outlined above were about to take place that put cross channel into active planning for calendar 1944! This was not done, even at the most private and secret war conferences, with any clarion statement. It was just that key divisions and key leadership would begin to leave the Mediterranean. The Mediterranean war went on, but these changes foretold a pressure role for the Allied presence in Italy rather than a breakout strategy. Finally, as executed in August of 1944 almost a year later, the invasion of Southern France was part of the cross channel invasion strategy. The invasion of Southern France at last found Churchill and his U.S. Allies agreed on how that operation fit the overall picture even while Churchill disagreed that it should occur at all.

Aftermath of Sicily

Palermo fell on 22 July 1943. Mussolini told the Italian King (Victor Emmanuel) on July 25 that he, Mussolini, was all through. Marshal Badoglio was appointed to head the Italian government and its armed forces.

Beginning on 10 August, across planned water routes and in planned stages, the Germans got 200,000 men out of Sicily and safely across the Straits of Messina. This included a number of near intact Panzer Divisions. Although many Italian soldiers had surrendered to the Allies in Sicily, the Italians, too, evacuated many units intact. With 350,000 men available in Sicily at the beginning of the Allied invasion, and with the reenforcements they had moved into Sicily from Italy, the Axis had made a major commitment there. Sustaining that commitment was predicated by the German high command on success in the field. With the fall of Palermo, Syracuse and Augusta in the early stages of the Allied effort in Sicily, the German high command had one goal, to extricate their forces and make their stand in Italy. Their plan to extricate had been made as part of their plan to commit.

The Allies had no strategy in making to prevent this. The opportunity was there. While uncertainty existed in Allied minds concerning the war intentions of Italian surface Navy forces, the Italian Navy was for the most part absent from Axis defense activity. Britain and the U.S. had the naval forces for interdiction of the Axis retreat across the Straits of Messina. The one-operation-at-a-time syndrome infected Allied planning and many felt that a major opportunity had been missed. Germany successfully executed an important, controlled retreat and would have her forces available for another day. Even if Allied commanders had generated an ad hoc plan, the fact that their own air forces, both U.S. and British, were "out of the loop" pursuing their own war, meant that the complete echelon of the top Allied commanders, land, sea, and air were not even comparing notes. Our forces had made a successful landing in Sicily. Allied land forces went on from there with little variation from the originally planned routes and fought brave and clear to the Straits of Messina. The U.S. Army and U.S. Navy almost nightly conducted locally conceived leap frog attacks along the north coast of Sicily on the road to Messina. Toward the end of the campaign in Sicily the Axis forces were moving out faster than we were moving in. A major foray into the heart of the Axis evacuation across the Straits of Messina was never conceived, let alone executed.

Worlds Apart, Salerno Was More Like The Pacific

This is not to say that Salerno and Tarawa were the same. Fortress Europe was a continent. Roosevelt and Churchill, though at issue on specifics, never deviated from the manpower priority given to the defeat of Hitler. Even with his monumental misjudgement of June 1941 in turning on his "ally", Russia, Hitler still extracted a horrible death toll in his defense of Europe. The U.S. cemetery at Anzio is just one reminder of German effectiveness in defending Italy and keeping Allied forces there from sweeping up into Europe proper.

The "Japanese Empire" had no continent. It was a string of captured islands, some large, some small, with a limited continental stronghold or two thrown in where needed. The contest to dislodge the Japanese from these islands was first a strategy to terminate the expansion of Japanese hegemony, and then one by one, and very selectively, to gain or gain back the key points the U.S. needed for the final assault on Japan itself. The carnage in most every landing the U.S. made in the road back was particularly horrible in terms of the percentage casualties to the numbers of troops involved on both sides. The U.S. was not dominant numerically in the beginning and the critically important U.S. tactic was to interdict by sea any attempt the Japanese undertook to bring in reinforcements.

Up until Sicily, a main challenge for the Allies against Hitler was long supply lines. For his part, Hitler was still facing a large potential number of attack points that the Allies might choose. In North Africa and at Sicily, the Allies put ashore numerically stronger forces than the defenders could commit directly at the beachheads; the Allied attackers then tried to work fast enough so that the defenders could not move their defense-in-depth troops or armor fast enough to gain local superiority. By Salerno, the shorter perimeters of the defenses began to work more toward the German advantage. The uncertainties faced by the German high command of where we would attack became less. At Salerno, the land forces available at the points of attack moved toward parity. The defenders still had more air bases, though the Allies had captured enough of them to give a good account of themselves in the air. It was in surface based sea forces that the Allies had the major advantage. The Italian Surrender just added to the uncertainty element present in all military strike operations.

Although the strategic balance was shifting toward the Allies, at Salerno the German defender enjoyed something of the tactical parity that Japanese defenders of the Pacific islands enjoyed at the point of engagement. In troops and in armor, the defenders at the beaches of Salerno in the early hours had a superiority. This would be the advantage the Japanese held in almost all the early contested landings in the Nimitz/MacArthur rollback campaign in the Pacific. The differences were important. The Japanese could not "fall back" to some mountain stronghold. This undoubtedly increased their acknowledged ferocity in combat. The Japanese Navy could, and did, contest the combat sea forces that the U.S. employed in getting its assault forces to the beaches. The Japanese won their share of those sea battles but in no case did they prevent the U.S. attackers from gaining and holding the beachhead. Learning from Guadalcanal and Tarawa, the U.S. increased the intensity and duration of pre-landing bombardments. That lesson took longer to sink in in the Mediterranean. Hitler's U-boats took a heavy toll of Allied warships in the Mediterranean but in no case did this prevent the Allies from establishing and controlling the beachhead that was their initial objective.

At Salerno, the D-day toll in lives lost by soldiers and seamen was high, especially high as a percent of those engaged. Despite the fact that Salerno was in doubt all day on D-day, and the operation's immediate objectives in doubt until D+6, the Allied land forces fought their way in foot by foot, and eventually achieved the breakout from the beachhead that is the objective of any such concentrated effort. The Edison played a key role on D-day at Salerno.

The Toe and The Boot

The foot of the Italian Peninsula is characterized as a "toe" and a "boot". The Allies put in progress important tactical operations there in early September 1943. The British Eighth Army of British General Montgomery was entrusted with the move, which took place on 3 September. Landing craft, under cover of a heavy cross-strait British bombardment from sea and land, went ashore north of Reggio on the Italian peninsula's toe. A leapfrog operation up to Pizzo at the narrowest part of the foot engaged the tail end of the 29th Panzer Grenadiers moving north. This occurred on 8 September, the day the Italian armistice was announced. Admiral Cunningham, mindful again of the Italian "fleet in being", an important segment of which was at Taranto, had suggested to General Eisenhower (according to Samuel Eliot Morison in Volume IX of United States Naval Operations in World War II in which he credits Admiral Cunningham's "A Sailor's Odyssey) that he would supply the ships if Ike would supply the troops for the occupation of Taranto. He did supply all the ships except the USS Boise which was recruited away from D-day at Salerno to return to Bizerte and embark the last contingent of the British 1st Airborne Division which was committed to the Taranto occupation.

This was an interesting play, this "borrowing" of resources. Theoretically, Eisenhower "owned" all the resources. So he "loaned back" a British Division for Taranto. Cunningham, who was the overall sea commander, under Ike, in the Mediterranean, had to "borrow" a U.S. cruiser, which he had ticketed for the Salerno invasion, back from Ike, in order not to leave about 800 officers and men of the British 1st Airborne at Bizerte. Boise's aircraft were off loaded to provide space for nearly 100 jeeps. So, with British cruisers and minelayers pressed into service, supplemented by the USS Boise, the force sailed to Taranto on the evening of 8 September just as the AVALANCHE force gathered off the Bay of Salerno.

Cunningham brought along the British battleships HMS Howe and HMS King George V and a six destroyer screen just in case the Italian warships objected. On the afternoon of 9 September, two Italian battleships and three cruisers stood out of Taranto. No shot was fired. The Italian fleet passed the British fleet and proceeded on its way to designated surrender ports. While planes pass in seconds, ships pass in hours. During those hours, a German observation plane might have taken an air photograph which would have provided German air intelligence officers any number of scenarios.

The British cruisers entered Taranto harbor at dusk on September 9th, and took pilots aboard, according to Morison's fascinating story of this event. Those Italian ship pilots must have had a busy day, one fleet leaving, and another coming!

"Buon giorno, pilota. Mi permetta di presentare il capitano de Fregata, il signor Thebaud."

So begins and ends my two years study of Italian at the U.S. Naval Academy. It was designed for just the situation that Boise encountered at Taranto, but alas, I was up at Salerno unable to assist Captain Thebaud of the USS Boise in his dialogue with the Italian ship pilot.

The Taranto occupation was comparatively peaceful and Allied troops went on to occupy nearby Bari, an important Italian port on the Adriatic side of Italy, later the scene of one of the worst ammunition conflagrations of all time. Montgomery's Eighth Army made ready to move northward, out of Calabria as the general area is called. The Allied cruisers then departed Taranto, proceeded through the Straits of Messina, and joined the battle for the beaches at Salerno, already in progress.

Uncertainty

As had occurred with French Admiral Darlan in North Africa, secret negotiations between General Eisenhower's representative and a representative of the Badoglio government took place before the Allied landings at Salerno. I am struck now by the bravery of these emissary/ negotiators who took enormous personal risks to pass through contested territory across "enemy" lines to conduct discussions. Also, those who did this on both sides never had a full hand to deal from. Anyone who wants to surrender wants to know that the other party has an irrevocable resolve to invade, and wants the essential detail on where it will take place. General Eisenhower's emissaries, Walter Bedell Smith for Italy and General Mark Clark for North Africa were not delegated authority to reveal this information. Irrespective of any agreements negotiated, therefore, the ideal was not reached in either case that would give the tactical commander of the invasion forces any sort of knowledge-certain about predisposition of "enemy" forces.

And, who was the enemy, anyway? An agreement of sorts was reached with Badoglio on September 3, 1943, after which, in effect, Italy was out of the war. Surrender? Armistice? U.S. General Maxwell Taylor of the 82nd U.S. Airborne Division was also involved in a spinoff negotiation with the Italians about a paratroop drop on Rome, but this was called off due to uncertainties on both the part of Eisenhower's representatives and Badoglio's about whether each side was telling all that it knew. General Eisenhower chose to announce the original deal at 1830 September 8, 1943, and, forewarned as to time and frequency, many on the invasion ships listened to his broadcast. While the desired result of "coming over" to the Allied side by intact units of the Italian Army and Air Force did not occur, the German hold on the peninsula being so strong, the Italian Navy did carry out the terms of the Armistice. The land bound units of Italy's armed forces just sort of "melted away", according to Samuel Eliot Morison. The Italian Navy, sortieing from northern Italian ports and from Corsica and Sardinia, to designated Allied surrender ports, took a fearful beating from the Luftwaffe in which a number of ships were lost, with great loss of life. The Allies, occupied with the Salerno landing, could give them no help.

Allied Force Structure for Salerno

The naval force structure had not changed. Reporting to Eisenhower, Admiral Cunningham, RN, headed up the overall naval forces structure. Admiral Hewitt, now in a fully equipped flagship, USS Ancon, had the responsibility for all amphibious forces and for Royal Navy covering forces-the big ships further offshore. The Northern Attack Force was led by British Commodore Oliver RN and the Southern Attack Force aimed at its assigned beaches at Paestum was led by U.S. Rear Admiral Hall.

Aboard Ancon was General Mark Clark, commanding the newly designated U.S. 5th Army. This Army was to be put ashore in the U.S. sector, which was southeast of the British sector. An important new U.S. Army division, the 36th was in the assault wave. Clark had been picked by Eisenhower and reported directly to him once established ashore. The British X Corps for the Northern sector was commanded by LGEN McCreery who had replaced a British General wounded in a Bizerte air raid just a few days earlier. Major General Dawley USA led U.S. troops in the Southern sector.

Montgomery's British 8th Army would be fighting northward to make a juncture with the Fifth Army. Their progress was not fast enough to bring them into position to interfere with the German decision to make an all-out defense at the beachhead in Salerno.

The JCS (U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff) had given back to Admiral Cunningham one of his British carriers and four of his British converted-hull escort carriers. This gave the Seafires, the carrier equivalent of the Spitfires, adequate time on station over Salerno. The land based Spitfires had 180 miles to fly from Sicily, giving them just about one half hour over the attack area. For the first time, a fighter-director team under a U.S. Army Air Forces Brigadier General was embarked on the USS Ancon with Hewitt and his staff.

Company Overhead

While we had seen the scouting planes from the U.S. Navy cruisers and battleships, occasionally at Casablanca, and from just the cruisers at Sicily, the air combats had taken place mainly out of sight of Navy ships. At Salerno, we became more aware of what was going on upstairs. The Luftwaffe furnished their brand of entertainment to the ships at sea, delivered for the most part by Junkers JU-88s and Dornier DO-217s. These delivered bombs and torpedoes, and the latter launched a new version of "guided" bombs. A JU-88 is pictured in an earlier chapter. (I was not able to get a good picture of a DO-217 for this chapter.)

Airborne "friendlies" became much more visible. For high cover, the Supermarine Spitfire, with an elliptical wing readily visible in good weather at 20,000 feet, was a most welcome partner. Spitfires provided our principal high altitude air cover at Salerno. One is pictured below.

Next to be pictured is a U.S. Navy recognition shot of a Spitfire. Labeled the Spitfire XII, it has had its wings clipped and would have been much harder for a sailor to identify at 20,000 feet without that beautiful elliptical wing.

The Spits and the British Hawker Hurricane were powered by the Rolls Royce Merlin engine, of just over 1,000 horsepower. This in-line, liquid cooled engine was a breakthrough in engine design and provided nimble, fast ,single-engine aircraft performance for the British.

Legions of workers on the U.S. home front provided not only the steady supply of new warships needed for the ambitious Allied counteroffensives, but also mass-produced, competitive aircraft. Here is a picture taken from Little Friends, a beautifully written and illustrated Random House publication. This young lady is working on a P-38 Lockheed Lightning. In the Mediterranean, these aircraft were used for low level bombing and strafing of enemy positions. In other war sectors, they escorted bombers.

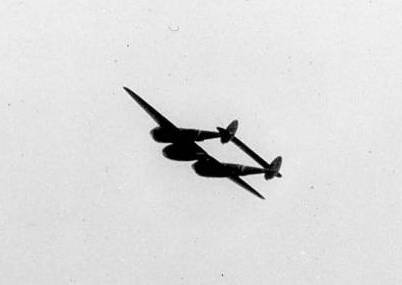

One day off Italy, two P-38s in perfect formation came roaring out of the foothills over the water making their exit from an attack at less than 500 feet and not a half mile from Edison. The wingman in the formation then made a graceful, tangential descent at high speed, finally impacting the sea and sinking immediately. We were at the spot in seconds. Roiled, soiled water was all we could find. The pilot had undoubtedly been hit by flak, went unconscious, relaxed his hand on the stick and throttle, and flew to a graceful, sudden death. Here is a U.S. Navy recognition picture of the Lightning.

Toward the end of the major portion of the Italian campaign, the U.S. Army Air Forces got another fighter into mass production. That was the P-51 Mustang, which replaced P-40 Warhawks as both a low level fighter bomber and high level escort plane. It had longer legs than the Spitfire. Apparently the U.S. Navy recognition set available to me was one made relatively early in the war. For that reason, the Mustang below is a drawing, and this was used in lieu of a photo for recognition training.

The P51 marked the end of the military reign of the liquid cooled piston engined aircraft. Liquid cooling provided high performance but also a possibility for catastrophic engine failure. The Republic P-47 Thunderbolt, which we did not see in the Med, joined the battle for Western Europe with its air cooled engine. All the U.S. Navy carrier aircraft's engines had been air cooled for years, though we did not see them in the Med either. This changeover to aircooled piston engines passed quickly as Germany introduced all jet aircraft before the end of the war. Allied air forces abandoned the piston engine for combat aircraft after the end of WW II.

The U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff

In reviewing some history to prepare for this story, it was almost like looking under the covers to piece together the role of the U.S. very high command (Joint Chiefs of Staff-JCS) in prioritizing manpower for Europe over the Pacific. Behind each move, one can see not just a JCS focus on the Normandy invasion and the consolidation of a viable Allied force position in Western Europe, but the JCS focus beyond Europe. The Churchill/Roosevelt agreement that Europe and the Axis had priority over Japan and the Pacific was always honored, but to the JCS, that commitment was also the prerequisite for getting at the Japanese. While they did not exercise overt veto power over specific actions in the Mediterranean, the JCS had the ultimate power of allocation of resources. The Chiefs grasped the strength of the U.S. as the arsenal of democracy, and they grew with this new United States as it was blossoming into a world power. In providing sufficient forces for the Mediterranean up to and including Salerno, the JCS exercised rationing control over essential systems like carriers. The JCS forced the focus back to cross channel invasion plans for 1944 by the manner in which they rationed manpower. The major persons on stage were the Eisenhowers, Montgomerys, Pattons, Clarks, Tedders, Alexanders, Cunninghams, and Hewitts, and of course Churchill and Roosevelt. But the men behind the scenes determining what future actions could be undertaken were the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff. They had Nimitz and MacArthur and the Pacific on their mind at all times. Marshall, King and Arnold were not always in the public eye, but they were tuned to these most fundamental changes in the world power structure.

Departure

Major convoys with heavy escort forces began to leave North African ports as early as 3 September. The principal assault convoy for the Southern Attack Force left Oran on 5 September and included the U.S. Army's 36th Infantry Division in 13 transports escorted by Philadelphia, Savannah and 12 destroyers. Admiral Hewitt on USS Ancon, accompanied by HMS Palomares, and US destroyers Bristol, Nicholson and Edison left Algiers on 6 September.

Geography

The Bay of Salerno was like a broad letter U, opened to the southwest, with the beaches roughly on a northwest-southeast line. The American sector was to the south with four beaches, and the British were just to the northwest with six beaches. There was a gap between the assault sectors. Salerno had the finest beaches we would find in the Mediterranean campaign and the Germans knew this too. The next harbor north was beautiful Naples, U-shaped and also open to the southwest, and flanked by the Isle d'Ischia on the north and the Isle of Capri on the south. The Germans knew we would want Naples, one of the world's great harbors. The British forces moved into Salerno with Capri to their port side, and on the clear, golden sunset evening of the 8th during the approach, and on a perfect weather D-day itself, Capri was quite visible to the British.

The Human Equation

General Clark was interviewed by author Quentin Reynolds during transit of the USS Ancon to Salerno on the 8th of September 1943. We will select just a few lines of that interview from the volume, "United States Navy in World War II" , compiled and edited by S.E. Smith and published by William Morrow.

Reynolds: Are you apprehensive of what their air will do?

Clark: I'm scared stiff of what their air will do, but we hope to have two of their air fields by D plus 2 and then our fighters won't have that long pull from Sicily.

Reynolds: When do you expect to establish headquarters ashore?

Clark: If everything goes according to plan-and it never does-I may get ashore on D plus 2.

Destroyer sailors might also be interested in how Comdr. D.H. Swinson USNR, Ancon's Executive Officer, helped prepare his ship's company for General Quarters. This according to a "Plan of the day for Thursday 9 September 1943 on USS Ancon (AGC4) as reported in the "United States Navy in World War II." "Food will be brought to General Quarters stations in food carriers by men detailed from ammunition parties." ......Gun platform crews will provide three fathoms of manila line for hoisting and lowering 10-gallon Aervoid coffee containers."

Captain Headden on the USS Edison always told us, "A hungry tiger is a fighting tiger."

Who Gets There First

Since the assault waves and the minesweepers were usually "engaged" before the "backup" fire support ships went into action, I will include some comments by Commander W. J. Burke and author William Bradford Huie in their joint offering, "The Panzers Were Waiting For Us", in the compilation, "The United States Navy in World War II."

"About 0320, in pitch darkness, the rocket craft let go their barrage....They were fired in bunches, enveloping their craft in brilliant sheets of flame, then soaring high up, over and down toward the beach where thunderous explosions took place. ( Author note: This pre-landing bombardment was new, the rockets were new, and the whoosh they gave off was a terrifying sound.)

At 0330...the first waves of the assault troops landed in their small craft...followed by waves of LCVPs, LCIs and LCTs....Sometime around 0430 four German artillery shells fell into the water near our causeway. ( authors were in an LST with causeways rigged)

At 0525 our ship, with causeways rigged for `momentum beaching', was ordered to Green Beach. (This episode and the Green Beach referred to were in the British sector.) We were following the course of the YM minesweepers (the smaller U.S. wooden jobs, not as big as the metal hulled fleet AM minesweepers) when, about a mile off shore a large size Italian mine which had been swept to the surface, but not exploded, loomed in the path of the ship. The forward lookout saw the ominous round shape and a frantic effort was made to veer the ship to port, but not enough. The curved end of the inboard causeway hit and rode up over the mine before going off against the side of the ship.......There was a blinding flame, water towered up, objects were hurled aloft, then a blast of air and a deluge of water and oil fell on us....The explosion ripped into troop quarters killing and seriously injuring a number of British soldiers.

....We grounded about 0600 without our causeways, some 250 feet off the shore line and about 11 feet of water at the bow ramp....It was immediately apparent that the beach had not yet been taken. Batteries of 88s and mortars had the range of the beach and kept up the shelling all through D-day. .....We decided to retract and attempt to put our cargo ashore.....via LCTs....When we were about a half mile off the beach, a British destroyer laid a smoke screen which protected us from further fire......

Ensign M.T. Jacobs, a former TVA engineer takes up the story of his LST. We were carrying men of a Hampshire Regiment of the 46th British Division. On the tank deck we had six Shermans, with a lot of half-tracks, Bren gun carriers, and ducks .(these were the DUKWs which performed so well in all Mediterranean assaults)..It was a clear night with a million stars but no moon.

The 16th Panzers were ready for us. When the small craft began hitting the beach, the Panzers opened up with everything they had. Big guns, 88s and machine guns. Our warships including the cruisers Savannah, Boise and Philadelphia were with the Southern Attack Force off Paestum, and they returned the fire. (I doubt if the Boise had really made it back from her mission at Taranto as early as D-day.) The Savannah had pulled to within a few hundred feet our LST, and she was blasting with everything she had. German bombers started coming over, so even the guns on the LSTs started firing. God, it was hot! And right at that moment we got the order to prepare to launch the causeways.

Off to my left as we were going in, I could see another LST with her set of causeways. That was Lieutenant Commander Burke, our officer-in-charge, with Mitchell and Look. ....When we were about a mile off the beach, the causeways ridden by Look and his men hit a loose mine, and there was one helluvan explosion. ....Look and most of his twenty-four men were blown off the causeway by that explosion....

About 0620-just before sunup-we hit the beach full speed....The beach condition was such that our LST slid right on up to the water's edge..we didn't need the causeways. All we had to do was throw a few sandbags under her ramp and spread the mat...We began unloading our LST and had her unloaded by 0800....That was the best beach we'll ever see for LST operations....Shellfire from the 88s was still bothering us on the beach.....Seven or eight Hampshires decided they'd brew up a spot of tea on the beach...They lit a fire and had the water boiling when one of them called to me. "Say, chappie, come and have a spot o' tea." I started walking toward them and was within fifty feet of them when a land mine went off right under that fire. ....when I got up every damn one of those Hampshires was dead and mangled...We stayed on the beach for ten days.. the bombing, shelling and fighting continued almost constantly...".

Part II - Edison In Action

Southern Attack Force; USS Philadelphia

The cruisers were able to lend an earlier hand to the landings in the British sector in the north because some progress was being made there, despite the mines and the vigorous defense ashore. The situation in the American sector landings to the south was grave. Here, the heavily mined approaches had interfered even more with the landing craft and with the access by the fire support destroyers and cruisers. Ashore, the situation grew desperate. Many SFCPs had been wiped out and those that survived were under fire and had difficulty establishing communication with their designated ship.

In seeking yet another report from the minesweeping commander, Rear Admiral Lyal Davidson got an unwelcome answer on the TBS voice circuit, "They're popping up all over the place. There is no channel for you yet." This was midmorning on the 9th and though I could not see the Admiral say these words, I could understand his state of mind as I recall the gist of his response, "Stop talking (on this voice circuit) about mines popping up all over the place. I can accept your assessment that there is no safe channel. Just get on with your job. I am coming in." With that the Admiral directed the skipper of the Philadelphia, Captain Hendren, to move through the minefield and get inshore of it for close, and if possible, direct observation fire support.

The light cruiser USS Philadelphia

What The Edison Did Then

Our skipper, "Hap" Pearce took all this in and made his own plan on the spot. We had made contact with the Savannah's SFCP. They had more targets than Savannah could handle. When the Philadelphia made her bold move, we were close to her. Pearce knew that his sonarmen had developed moored mine detection experience off Porto Empodocle at Sicily and he determined that the USS Philadelphia was by far the best minesweeper in sight. He gave orders to the helmsman and the engine room to have Edison fall in right behind Philadelphia. I had never seen the big box stern of a cruiser that size so close ahead. I had to look up at an angle of at least 45 degrees to read her lettering. I will never forget that scene. For the only time I can recall in the five attack landings in which we participated in at North Africa and the Mediterranean, I felt an exhilaration as Edison made her move. We both made it in and then ensued the most action-filled, harrowing, and fulfilled day of Edison's life.

Lt. Stanley Craw was usually back on the after deckhouse with me when we were at General Quarters. I was there to provide some direction to the secondary guns, the 40s and the 20s. Lt. Craw was there primarily because he would become the after conning officer if our bridge controls were disabled or destroyed. He also helped with gunfire direction. After the Edison made her move to get inboard of the minefield and get into position for shore bombardment, the ship's control officers, Captain Pearce and Executive Officer Jake Boyd knew they'd be in for a busy day. We would be dodging bombs, counter fire from the beach, and mines. Edison's radar and sonar operators were able to help define a narrow operating zone between the minefield and the shore. Navigation information would need to be refined, and be much more time-sensitive than usual. Even the fathometer became a war tool! An extra hand was needed on the bridge. Stan Craw provided another capability for a stretched out General Quarters bridge crew. He was called to the bridge and I was left alone topside aft to observe what was about to unfold.

Lt. Dick Hofer, the Gunnery Officer and his main battery gun crews were magnificent that day. But equal billing on the Edison for D-Day at Salerno had to go to the Seamanship effort. This was not just another shoot from long distance. This was an all day gunnery effort in cramped quarters, at high speed. We were not casually lying off Bloodsworth Island in the Chesapeake or even Cape Arzeu in Algeria. This was a total ship effort under combat conditions. I will transcribe below major excerpts from a typescript called "Salerno, First Day", which I wrote about 1960. The thoughts were then just over 15 years old. The action takes place in the Southern Attack Sector. The landing craft release point was about 6,000 yards (three nautical miles) from the shore, at the outer edge of the coordinates of the minefield. The sweepers worked tirelessly to sweep "channels" through the minefield.

The indented paragraphs below are taken from my 1960 typescript. They cover what the official War Diary of the USS Edison, written in Washington after the war, covers in the following eight lines of typescript. " She screened the minesweepers while they cleared the fire support area. At 0510 on 8 September (first error; should have been 9 September) DD 439's guns were trained inland for shore bombardment. Her targets were enemy troop concentrations, tanks, trucks, and artillery in the vicinity of Il Barizzo. Before leaving the area on 24 September (second error; Edison left on 10 September and returned several times before 24 September) en route to Mers-El-Kebir, two more air attacks developed though they were not pressed and all units escaped damage. All hands had an anxious moment (on 10 September) when a torpedo passed along Edison's port side only 100 yards abeam."

It was early evening on 8 September 1943 when the watch relayed the news that Badoglio had surrendered. I must say there was an immediate disposition to question just what Badoglio could surrender. As the hours wore on, however, the official broadcast made it sound as though Badoglio had been able to effect, in the name of the King, a surrender of all of the Italian Armed Forces. The degree of German military involvement in the Italian Peninsula was unknown to a Junior Grade Lieutenant aboard a U.S. destroyer. Early disbelief that anything could be won so easily gave way to a disposition to believe that matters would perhaps be somewhat easier on the morrow than had been anticipated. I believe that this statement accurately reflects the feeling of most of those men in the U.S. Armed Forces who were expecting to take part in the Salerno landings.

The beautiful weather which had made the approach so much like a War College textbook amphibious operation, certainly also provided any defender with a period of time, beginning on the afternoon of September 8th, to calculate our strength and arrange his beach defenses. The morning of September 9th commenced and it remained to be seen if the defender would fight.

Well, fight he did! Our minesweepers were the first forces in action, and they were totally engaged while dealing with the task of clearing dense mine fields. The story of our minesweeping operations in the Mediterranean Sea have never been comprehensively chronicled to my knowledge. By the time that H-Hour, D-Day, Salerno, arrived, it was apparent that the minesweepers had only just begun their task. My recollection is that some postponement of H-Hour was authorized. (Faulty. I can now find no corroboration of that.) The first waves to hit the beach (Southern Sector) were quite late.

Even in the early light of morning some casualties in the seaborne forces were already apparent. Numerous vessels were on fire and others were settling low in the water. Our own visual observation of the troops hitting the beach, later confirmed by fragmentary radio reports, showed that they were in a murderous crossfire. As the morning wore on our task force commander for gunfire support, Rear Admiral Lyal Davidson, became more and more impatient. His main concern, now that he had safely conducted his forces to the landing area, was to see that the troops got ashore. After the Admiral's fourth or fifth interrogation of the sweep commander, over the TBS, brought forth the response that the field was not swept, and that the mines were still popping up all over the place, Admiral Davidson himself exploded.......The Admiral must have been thinking of the morale effect on his ships associated with these reports of mines. He knew that most of his fire support destroyers and cruisers would have to penetrate the mine field if they were to provide effective gunfire support to the now badly off-balance landing forces. As a result, the Admiral commanded his Sweep Commander ( it should be remembered that these sweep people had been heavily engaged for many hours and had really done a magnificent job) not to report again the status of the sweeping operation in terms of "mines popping up all over the place". Then the Admiral announced tersely, "I am coming through." Admiral Davidson was embarked on USS Philadelphia, and true to his word, Philadelphia immediately started in.

The Philadelphia, the Brooklyn and the Savannah had been wonderful ships to us in the destroyer Navy. We had operated with them during convoy operations and then during amphibious operations commencing with the Casablanca landings, thence to Sicily and now Salerno. We would see them hammer away at Anzio and again at Southern France. This light cruiser class had been designed, I believe, to counter the Japanese 15-gun cruisers. Their big payoff in the Mediterranean came, however, in the fire power of their six inch guns in support of amphibious operations. AA-wise they were perhaps slightly deficient but hull integrity-wise, as Captain Cary and his crew so courageously demonstrated in Savannah just a few days later, they could take an awful wallop and survive.

A destroyer sailor who could read the word, PHILADELPHIA, across a big gray box stern, as though he were taking a visual acuity test in some optometrist's parlor, might develop quite a fright that collision was imminent. Commander `Hap" Pearce decided to put his bow within a few feet of that cruiser's stern and go in with her. It was a good time for spelling practice on Edison's focs'le. A good many years later when I learned more about the characteristics of mines (an assignment as the U.S. Navy's Undersea Warfare Development officer), I reevaluated Hap's decision and concluded it was a good one, although some might reasonably disagree. At any rate, we went in with Philadelphia and got through the field without casualty. The field had been well planned and executed, but for the type of operation which ensued, the field gave us precious sea room just short of the three fathom line. (Looking back, I figure a destroyer had a two mile band between going aground ashore and the inner edge of the mine field. For a cruiser, the fit was very tight.) So for the next 6 hours, Edison danced along a thin line.

The situation ashore was so confused that no one seemed able to establish effective contact with their assigned Shore Fire Control Party. The cruisers were doing some direct interdiction fire (at longer ranges than they would have preferred for that type of fire). This was always a little risky because of the possibility of mistaking own forces for enemy forces. I would like to make it clear that the people at sea could always see the picture a good deal better than they were given credit for by the Army ashore.

We could see that other ships had not been so successful as we in getting through the mine field. I can remember HMS Abercrombie, that grand old name which was just recently (circa 1960) stricken from the British Naval Register, very low in the water from a mine and no longer able to shoot. Other craft were similarly plagued. It is my recollection that we were the first or among the first to make contact with a Shore Fire Control Party. I believe we finally established contact with a party designated for USS Savannah. Either Savannah had been unable to contact this party or had passed the contact to us because of our better position with respect to the NLO. A word about this NLO. The term stands for Naval Liaison Officer. This man was assigned to the artillery ashore. He usually worked with an Army artillery spotter as a member of a Shore Fire Control Party (SFCP). An Army radio technician was assigned and also a poor arm-weary GI who did nothing but crank for power. These parties were unbelievably courageous and effective. In the fluid situation at Salerno on D-Day, this small party was often the advance group, deep in enemy held territory. (At Salerno, "deep" could be measured in feet or yards)

The Germans were now making a terrific counterattack on our precarious landing area. Some of the Tiger (Mark VI) tanks were actually moving southward along the beach to the beachhead. We (the Edison) were faced with counter battery fire from these tanks and other Wehrmacht gun emplacements throughout the remainder of this engagement. The flat trajectoried 88 mm shell had a unique piercing sound as it passed between our Director and the #1 stack. We had been used to the fluttery sound of larger projectiles in arched trajectories. (Like our 5" 38s, most enemy artillery projectiles were subsonic. The 88, I later learned, had a 4,000 feet per second muzzle velocity, and when you heard the sound, the projectile was long gone. At Salerno ranges, the 88 shell was in a very flat trajectory, where a "miss was as good as a mile", usually more. They had to hit you directly and hope you had enough metal to set off their fuze, which was essentially designed to be anti tank, armor piercing.)

We got right down to business with our newly adopted SFCP and went to work. From my own station in secondary AA on the after deck house, although we had a few air attacks the first afternoon, I was able to get quite a perspective on our participation in the engagement. The Skipper and the Gun Boss teamed up in a driving and dynamic display of destroyer gun power. The Exec. and Navigator teamed up in a most difficult job of high-speed navigation in restricted waters, while opening up fire lanes for the 5" guns. Some unseen bond between these two teams kept matters from getting completely out of hand. The Captain wanted to present an unpredictable target to enemy fire while maintaining our guns on firing bearings for long periods of time. I am sure the Exec. and Navigator did not actually have time to think about Rocks and Shoals (the vernacular name for Navy Regulations), as they kept us from straying back into the mine field to seaward or running aground on Salerno's shores. The engineers supplied flank emergency ahead and back in total disregard of acceleration curves.(Since we were firing almost all of the time , and the water was full of spent cartridge cases-"brass"- it needs to be added that the firing cut-out cams would take Guns #1 and #2 out of action, or Guns #3 and #4, depending on how fast we could turn in that mine safety zone and get going the other way.) All the "systems" worked perfectly. Guns and engines and boilers are stress-tested to some per cent over normal, and the Edison worked that extra percent all the time in the no man's land of Salerno. Yes, we had to be rebricked and regunned after Salerno, but the systems never failed under those punishing conditions.

On some of the early targets, we had to fire rapid continuous (about 20 rounds per gun per minute) fire for one, two and in one grueling demonstration, for six minutes at a time. Although our "doctrine" told us this could be uneconomical of projectiles (rapid "timed" fire was better) the "spot" from the NLO was "on" and the urgency in his voice conveyed to us a requirement for extreme performance. Later we went to continuous timed fire, more economical of projectiles and nearly as effective on a per unit time basis. The Army's Artillery General Officer ashore who was fighting this phase of his battle with our artillery, sent repeated messages of encouragement. Finally, in the waning hours of daylight, as we left the firing scene, he sent one of the most magnificent messages of appreciation to Rear Admiral Lyal Davidson that I have ever seen recorded. "Thank God for the fire of the blue-belly Navy ships. Probably could not have stuck out Blue and Yellow beaches. Brave fellows these; tell them so. General Lange." Later and without waste of language, he told vividly of tanks piled up in rubble and how attack after attack of the German forces had been blunted, and finally turned back, and the beachhead made secure. Again, by mail we received from this expressive and appreciative source, photographs showing the terrific damage inflicted on twelve German tanks. They were piled up like scrap iron. Many of us were truly amazed at the localization of effective blast damage from concentrated 5" 38 HC fire.

Those two dreaded destroyer shortage bugaboos may have been temporarily banished from mind, but inexorably we shot up our precious supply of ammunition and used up a significant measure of our limited supply of bunker fuel. Split plant, four boilers and those accelerations had taken a toll on our fuel. The projectile count by late afternoon (still 9 September) told its story. There were just a few high capacity projectiles left, all up in the handling rooms, directly under the guns served. We had expended about 1200 5" 38 HC shells. A few odd star shells were still available, some white phosphorus, and although my memory is rather dim on it, I believe we had a few armor piercing aboard. (We also carried and never used the VT fuzed shells, sometimes referred to as "influence fuzes." ) We had started the day with extra HC projectiles and powder cartridges over and above our allowance. These had been lashed in the handling rooms. It was forbidden by Higher Authority and we would have had to reckon with this had we encountered rough weather. (In rough seas, we had experienced loose 5" projectiles from the #2 handling room falling through the hatch over the officer's bunkroom passageway, and sloshing into the wardroom.)

Though it was not fully apparent until dark, the guns on Edison were for the first time in my experience all white hot. They continued to glow on into the night, gradually subsiding to red, then dying out though still hot to the touch. The canvas tarp covering Gun #3 to save topside weight had long since evaporated in flame. All the bloomers were completely destroyed. About mid-afternoon when we reported our ammunition state, we knew we were going to have to leave the firing area to make way for a ship which still had some punch in her. (It turned out to be the USS Trippe.) Edison was all shot out. (I used the term "firing area" when I originally put down these thoughts without realizing that this was not a firing area in any operation plan. Admiral Davidson and our Skipper "Hap" Pearce had carved out a firing area and this became by usage, the firing area.)

I can honestly say that a good many of us were just a little relieved at the opportunity to back off and light a cigarette. By late afternoon, the sweepers had marked the channels and we were somewhat easier going through the field on the way out than we had been on the way in. Darkness was beginning to set in as we were directed to assist in screening some of the attack transports which were still disgorging their human cargo.

Unfortunately, it wasn't quite over yet. We departed the Salerno area, screening larger ships astern, on the next evening (10 September 1943), another hazy bright Italian moonlight night. The number of ghosts on our radarscopes was almost beyond anything we had ever seen. And how rapidly they moved! Edison's engineering force was again put to the test as we attempted to pursue these phantoms and come to grips with them. All of a sudden, we saw that characteristic orange flash. I had seen it before with the USS Ingraham in the North Atlantic. It was the mark of a ship whose magazines has exploded and was entirely different from the muffled poof near a transport, for example, when these were hit below the water line. It turned out to be the USS Rowan, a destroyer in our force, which had also gotten in her share of shelling that day. ( I learned later there was a heavy loss of life, and one lost was Lt. (Jg) Wiley Mackie USN, a USNA classmate.) The USS Bristol turned back to assist the stricken ship. All Bristol could do was pick up survivors, some badly injured, as the Rowan was doomed. I do not know if the cause of the Rowan's loss has ever been completely determined, but most of us felt it probably had been either an E-boat torpedo attack as evidenced by the radar phantoms, or a submarine lying in wait. Or again, it may have been one of the moored mines which had been cut loose, and drifted into the path of the Rowan.

Salerno's first phase, for Edison, ended the following morning (September 11th) in Oran when we tied up. The destroyerman's view of an operation, while not claimed to be as complete a view of the operation as a plans or staff man, is certainly a first hand view. The destroyer man sees the little fellow, and the big fellow, and he must work with them both. I certainly do not recall that Edison ever had a period of time in which the action was more intense, the enemy more tenacious, and the issue so starkly defined. The mine field certainly disrupted our timetable and increased our casualties. The timetable in turn caused at least one U.S. infantry division not scheduled for Salerno to be diverted into the combat area.

On April 18, 1991, my wife Peggy and I were helping one of my cousins with Dailey genealogy. I opened the suitcase my father gave me a few years before his death and the newsclip below fluttered to the floor. I had not seen it before. Very likely it came from the Rochester (N.Y.) Democrat & Chronicle or Rochester Times Union and he had cut it out some day in October 1943. It bears an Associated Press date of October 17, 1943. "News" traveled slowly in war time. The Bristol is misspelled as Briston.

Seamanship, Navigation, Engineering, Gunnery

Once Edison decided to match her fate with that of the USS Philadelphia and enter the minefield at Salerno, there were no ship formations to observe, no station keeping, and no ASW "slow weave". A sub here would have had to surface. There was no fuel economy plan. All boilers were on line. Nothing on Edison was going to be "saved" this day. Looking back, it was Edison herself that was saved. Lady luck helped a crew built on teamwork.

Don't run aground. Don't hit Philadelphia. Don't stray back into the minefield. One of the only two ships to make it inside the minefield by mid-morning to support the Southern Attack Force landings did not want to do to itself what the enemy was trying to accomplish, be put "out of action."

Rarely, if ever, is a ship pressed to the limits of its performance in seamanship, navigation, engineering and gunnery all at once. I can recall long winter convoys where an escort ship navigator could have gone to bed at the exit port sea buoy and need to be waked only at the entry port sea buoy. The Convoy Commander's ship could handle navigation and all the escort needed to do was to keep formation. This is an outrageous example to make a point. Convoy work is probably the most redundant work in the world.

Edison was either accelerating or slowing, making course reversals, dodging bombs or shells (mostly the latter), and straining eyeballs to see "floaters" as the drifting mines were called. The 5" main battery was in director automatic, pointed toward enemy beach armor at all times irrespective of the ship's course. The Wehrmacht's surviving tanks finally turned around! This was direct fire! Our Chief Fire Controlman, Jackson, had a clear view of this action in the rangefinder of his Mk 37 Director. Lt Dick Hofer, the Gunnery Officer coordinated the four gun crews as they strained to keep up the rates of fire demanded. His frequent loading machine drills paid off. No gun missed a salvo unless the firing cutout cams prevented its firing.

Subsequent to D-Day

The first day at Salerno was a maelstrom of air attacks, sea attacks, landings, and counterattacks. While Edison's principal contribution was made on D-Day, that day was by no means conclusive. In the subsequent days, the Germans organized a number of attacks which threatened the beachhead. For two days, the 13th and 14th, plans were even made to re-embark troops already ashore with the Southern Attack force to plug holes in the center between the British Northern Force and the U.S. Southern Force. This did not have to be carried out but it is revealing of the tenuous hold we had on the beachhead. Unfortunately, General Montgomery's pursuit northward of the Panzers found the latter disengaging and linking up with the German defenders of Salerno and participating in German counterattacks on the beachhead. Montgomery's units arrived on the 16th of September after the survival of the beachhead was assured. The British 8th Army did participate in the subsequent capture of Naples on October 1. This took place about 10 days late in the Allied timetable.

Morison, Volume IX; Edition with Preface Dated March 1954

Some of the following data is excerpted or paraphrased from Samuel Eliot Morison's Volume IX, pages 298-314, of the History of United States Naval Operations in World War II.

"Assault shipping was supposed to be unloaded by the end of 10 September, and except for a few LSTs at the southern beaches, that was done........Rear Admiral (John) Hall in (USS) Samuel Chase sailed for Oran with 15 unloaded transports and assault freighters, escorted by ten destroyers, at 2215 September 10....Shortly after midnight, destroyer Rowan of the transport screen sighted a torpedo wake about 100 feet distant on the starboard bow....There followed for the destroyer, USS Rowan, one of those in our group making ready to return to a rear base due to expendiuture of most of her 5" annunition, a period filled with fast moving radar targets, pursuit at 27 knots and Rowan gunfire, followed by a return to the convoy, then another radar target astern. In bringing her guns to bear on this target, Rowan was struck by a torpedo according to her action report and Admiral Hall's report. There was a tremendous explosion, probably in the after magazine, and she sank in 40 seconds. Bristol, detached from the transport screen, managed to rescue only 71 members of the crew. 202 officers and men went down with the ship. This sequence was also confirmed by an E-boat division commander after the war who thought he had, in fact, sunk a 10,000 ton freighter. (In Theodore Roscoe's "US Destroyer Operations in World War II", Roscoe states that Rowan's skipper, LCDR Ford survived the explosion and sinking, and that Ford credited a Torpedoman Mate 2/c with setting depth charges on safe in the few seconds before the Rowan sank. )

Radio controlled bombs rendered the SS Bushrod Washington on 14 September, and the SS James Marshall on 15 September, total losses.

(Our intelligence data on the USS Edison in 1943 provided us with descriptions of two distinct Luftwaffe bomb systems, both guided all the way from a "mother plane" to impact. One was an engine powered glide bomb, HS 293, which during the last part of its flight was right down on the water flying level until nosed down onto its target. We saw many attacks of this type, the favorite targets being the relatively slow-to-maneuver LSTs. Surface observers as well as controllers in the attacking plane could see the flare which the mother plane used to control the powered glider bomb, most often used in daylight attacks. The other, the FX 1400, was dropped from high altitude, and its ballistic trajectory could be altered by moving the tail vanes which stabilized the bomb. At night one could see the flare used to guide the tail vanes of the radio controlled ballistic bomb, but the bomb itself, used both day and night from high flying Dornier 217s, could only be seen in daylight in the last moments before impact.)

On page 283 of his Volume IX, Samuel Eliot Morison's account refers to radio controlled glide bombs, which I feel consisted of one basic system with two variations. It was rocket powered; one variation had a range of 8 miles and top speed of 570 mph and the other a range of 3 ½ miles but with top speed of 660 mph. Trading range for speed could have been a settable configuration of the same system prior to launch. This fits the description we had on board for the HS 293 glide bomb. This system had a warhead of about 600 pounds. This system is not the same as the trajectory alterable FX 1400 unpowered bomb that was shown in diagrams to us in 1943. Returning to Morison, on page 283, "Savannah was put out of action by one of these bombs." Radio controlled, yes, but not the rocket powered glide bomb but the far more deadly FX 1400 is what hit the Savannah, judging from the description below.

(This next sequence begins about 0930 on 11 September and culminates about 15 minutes later.)

"She was lying to in her support area, awaiting calls for gunfire support, at 0930 September 11, when 12 Focke-Wulfe 190s were reported approaching from the north. The cruiser rang up 10 knots speed, which she increased to 15 knots after a heavy bomb had exploded close aboard Philadelphia, nearby. (Philadelphia sailors told us later that this near miss lifted the entire stern of the ship out of the water.) Ten minutes later, Savannah received a direct hit on No. 3 turret. The bomb which had been dropped from a DO-217 from 18,000 feet, detonated in the lower handling room. The blast wiped out the crew of the stricken turret and the No. 1 damage control crew in the central station, blew a large hole in the ship's bottom and opened a seam in her side."

( For bomb and damage details, I am indebted to Drake Davis, the son of a Savannah sailor, who maintains a USS Savannah website. Drake refreshed my memory on the two distinct types of radio controlled bombs, which gave German "mother" planes a standoff bombing capability. Both of these bomb systems worked very well. For greater detail, Drake Davis' website http://www.concentric.net/~drake725/index_c.htm is highly recommended. The author characterized the bomb as a Fritz-x and even has a picture of it. It first opened about a two foot hole in Savannah's #3 turret, penetrated 34 inches of steel to get into the #3 magazine, where it then detonated. At Malta, in drydock, a 20-30 foot hole in the hull of the USS Savannah was exposed. The same weapon system was used in hitting a British cruiser. In this case, the bomb went all the way through the cruiser and detonated in the water under her keel!)

After many heroics, Savannah, for a time in a sinking condition without power, made it to Malta. Since the British, too, had a cruiser put out of action by a radio controlled bomb, two cruisers were ordered into the Salerno action area in relief. One of the relief ships ordered up from Malta was the cruiser HMS Penelope, with whom Edison later would put in many hours of work. The U.S. cruisers Boise and Philadelphia used 70% of their ammo during the 9-15 September period. Ammo for the cruisers was so tight, the destroyer USS Gleaves was ordered to Malta to bring back some of Savannah's 6" ammunition. And before the beachhead had really been secured, not only had the U.S. 36th and 45th Divisions been fully committed, but the 34th was to receive its baptism of fire and the 3rd was ordered up from Sicily. Important elements of the 82nd airborne also helped turn the tide.

While there were countermeasures ships at Salerno, notably the U.S. Destroyer Escorts, Herbert C. Jones and Frederick C. Davis, these were "getting their feet wet" so to speak, and I will go into some detail on what they managed to accomplish against radio controlled weapons and other German air tactics, in Chapter Nine on Anzio.

From Morison, Volume IX, page 296, a statement provided by the German Marshal Kesselring, "On 16 September, in order to evade the effective shelling from warships, I authorized a disengagement on the coastal front....."

Kesselring, though, had managed necessary withdrawals so effectively, and had shown such an intestinal willingness to dispute every inch of ground, that he was chosen by Hitler over Rommel stationed in the north of Italy to continue this dogged defense. Morison reasoned that had Rommel been under Kesselring's command during the Salerno beachhead battle, that Rommel's available divisions could have turned the tide in the German's favor and the Allies thrown back into the sea. For their part, in late September, the Allies missed many opportunities to interfere with the German evacuations of Sardinia and Corsica, where important German forces got out to help hold the Allies on a line north of Naples. Available French and Italian sea forces, under Allied direction, could have made those evacuations troublesome for the Germans.

Enemy Submarine Action

The U-boats were not finished with their favorite targets, U.S. destroyers. The USS Buck was patrolling at the north end of the Gulf of Salerno on 8 October. Pursuing an active radar contact, Buck was torpedoed by U-616 forward of her stack (she was a one-stacker). She went down in about four minutes with loss of life exacerbated by depth charge explosions. (Buck's XO was LCDR G. S. Lambert. As Edison's Gunnery Officer, "Beppo" Lambert had been an active proponent of Edison's defined policy to leave depth charges on "safe" except during actual pursuit of a submarine. My belief, therefore, is that Buck's "pattern" was set because she was on an attack run against a submarine.) Obviously, Buck had neither the time nor most likely the personnel or equipment left to send an SOS. Waterlogged survivors welcomed three rafts dropped by an Army transport at mid morning on October 9. The USS Gleaves was attracted by a Very pistol flare late on the 9th. Only 94 out of 260 had survived when the USS Plunkett and a British LCT arrived shortly after.

The photo above was furnished by Jack Dacey whose Uncle was lost on the USS Buck.

The following information was furnished in a phone call on 12/28/97 by Helmuth Timm, MM1/c, a survivor of the sinking of the USS Buck.

" It was between 11 p.m. and midnight on 8 October when we were hit. I was in the after engine room. She sank fast. I barely had time to kick my shoes off and get in the water with my life jacket on. The magazines did not go off but a 600 pound depth charge off the rack at the stern did go off as the hull sank, and caused death or severe concussion to men in the water. I watched my Chief Petty Officer, P.U. Baker, sink below the waves. After being in the water a long time, I was picked up late the next night. I was taken to the hospital at Palermo and later to one in North Africa. I was in the hospital about three months. I had a severe concussion and double pneumonia. Dugan, our Chief Water Tender was in the hospital with me. Pete Kielar, MM1/c, another survivor, has been in touch with me. I believe our skipper, LCDR Klein, who was lost in the sinking, received the Navy Cross for the sinking of that Italian submarine."

Mr. Timm recalled a Commander Durgin who was for a time the Squadron Commander of DesRON 13 during early Mediterranean duty but did not recall Captain Heffernan, who was ComDesRON 13 in the earlier North Atlantic convoys described in Chapter Four. It is quite likely that Commodore Heffernan's tour did not overlap Helmuth Timm's. ( E. R. "Eddie" Durgin (not to be confused with his brother Calvin T. Durgin, who was skipper of the USS Ranger at Casablanca), was relieved as ComDesRON 13 by CDR Harry Sanders on September 15, 1943. By this date, the DesRON 13 flag was no longer on the USS Buck but was on the USS Woolsey, DD437.) I found Mr. Timm very alert during our phone conversation but he protested, as do all of us at "our age", that he has difficulty remembering names. Mr. Timm is 82 and spoke from his son-in-law's home. His son-in-law is James Lingafelter, who assisted greatly in making this telephone call possible.

U-616

| Type | VIIC | |

|

Laid down |

20 May 1941 |

Blohm & Voss, Hamburg |

|

Commissioned |

2 April 1942 |

Oblt. Johann Spindlegger |

|

Commanders |

04.42 - 10.42 |

Oblt. Johann Spindlegger |

|

Career |

9 patrols |

04.42 - 12.42

8th Flotilla (Danzig) |

|

Successes |

Sank the US destroyer USS Buck (1,570 tons) |

|

|

Fate |

Sunk 17 May, 1944 in the Mediterranean east of Cartagena, in position 36.46N, 00.52E, by depth charges from the US destroyers USS Nields, Gleaves, Ellyson, Macomb, Hambleton, Rodman and Emmons, and by bombs from 3 British Wellington aircraft (Sqdn. 36), in a 3 day-long action. Entire crew, 53 men, survived in captivity. |

|

On 13 October, while the USS Bristol was escorting a Salerno-bound convoy off Algiers, she was torpedoed by U-371. This hit occurred near the forward stack (she was a two stacker.) and the ship buckled in the middle. Bristol had only detected the torpedo noise on her listening gear for ten seconds before she was hit. Fortunately, Bristol's depth charges were checked on safe by a Torpedoman's mate and Bristol had a little more time before she made her plunge than Buck. Even with the keel broken, if a destroyer is not hit in a magazine, she has a few minutes to abandon ship, a procedure that Navy vessels rehearse. 241 men out of Bristol's complement of 293 were saved by two destroyers. Edison shared many sea and sea combat experiences with both Bristol and Buck.

U-371

| Type | VIIC | |

|

Laid down |

17 Nov 1939 |

Howaldtswerke, Kiel |

|

Commissioned |

15 March 1941 |

Oblt. Heinrich Driver |

|

Commanders |

03.41 - 03.42 |

Kptlt. Heinrich Driver |

|

Career |

|

03.41 - 06.41

1st Flotilla (Kiel) |

|

Successes |

13 ships sunk for a total of 69,899 tons |

|

|

Fate |

Sunk at 0409 hrs on 4 May, 1944 in the Mediterranean north of Constantine, in position 37.49N, 05.39E, by depth charges from the US destroyer escorts USS Pride and Joseph E. Campbell, the French Senegalais and the British destroyer HMS Blankney. 3 dead, 48 survivors in captivity. |

|

Casualties

At Salerno, Morison's figures show the U.S. Navy with nearly 900 killed or missing and over 400 wounded. The U.S. Army lost over 2,000 killed or missing and had nearly 3,000 wounded. The British Army losses were heavier than the U.S. Army's casualties at Salerno. British Navy dead totaled 83, with 43 wounded.

Home | Joining The War At Sea | Triumph of Instrument Flight