The new Fourth Edition with 44-page Index

Joining the War at Sea 1939-1945

- Draftees or Volunteers

- U.S. Military Draft and Pearl Harbor

- Warship Building

- World War 2 U-Boat

- Collision at Sea

- Operation Torch

- Sea-based SG Radar

- Attack Transports Sink

- Assault Landing

- Tiger Tank

- Darby Rangers Setback

- Eisenhower Needed Seaports

- Rohna Sinks; 1000 Soldiers Perish

- Death, Survival, and Leyte Gulf

Rohna Tragedy Tops Transport, Destroyer Toll

300 warships/transports in "Joining the War at Sea" listed alphabetically

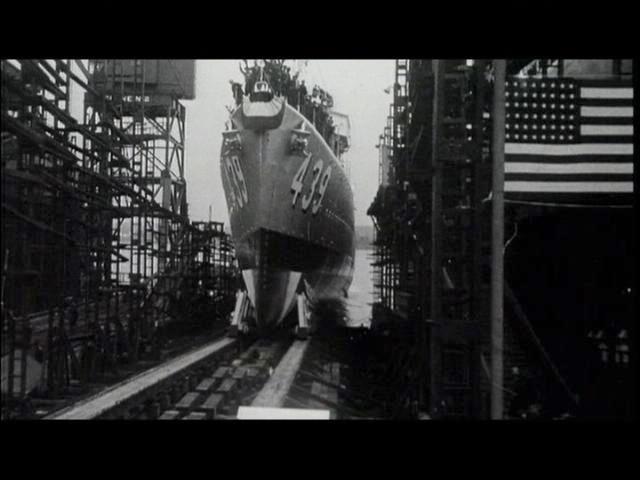

Launch of USS Edison, DD-439, Nov. 1940 at Federal Shipbuilding and Drydock, Kearny, NJ

: Thomas Edison's widow,& NJ Gov. Charles Edison do launch honors

Part I, Edison Begins Her Ship's Life (just below)

Then, in Part II., USS Edison, near the end of an active ship's life, makes a port visit to Nagasaki, Japan. This visit, which I learned about after writing the book pictured at left, also brought me back to a ship that meant survival in a bitter war for those who served aboard her. The photo also reunited me with some of the officers that had served with me in the Atlantic and Mediterranean sea ASW and five amphibious landings.

Copyright 2012 Franklyn E. Dailey Jr.

Part I, Edison Begins Her Ship's Life

Machinery: The coin of the realm in WW II was called "materiel", favoring the less ambiguous variant derived from the French of the word "material". It was materiel, authorized in the U.S. Lend/Lease programs of WW II, when it arrived at U.S. seaports and was loaded into and onto freighters, which were then formed, ship behind ship in six, eight or ten columns, in convoys stretched across the Atlantic. Steam locomotives and aircraft were lashed to the main decks of many freighters. On arrival at an overseas port, these were just one or two maintenance steps away from service and combat. The U.S. literally drowned its adversaries in materiel. Getting it there was a major effort and will be discussed in important episodes in this story.

The machinery at the heart of this story was called materiel when it was on its way, much of it on railroad flat cars, to the shipbuilding yards of the U.S.. After shaping, assembly and welding, this materiel became ship's hull and machinery. A warship was then launched and commissioned. In Edison's case, the champagne bottle was launched by Charles Edison's widow, with her son, Gov. Charles Edison (later Navy Secretary) of New Jersey looking on.

(In crediting Edison News as the source of information in this Chapter on details of the destroyer, USS Edison DD-439, it is appropriate to provide an insight into the "staying power" of her crew. This staying power served Edison well in convoy operations, in submarine and aircraft defense, and in shore bombardment, especially during the complex phase of getting landing craft to their debarkation point, onto the shore, and into defensible, expanding perimeters against resourceful, battle tested, enemy forces)

Edison's shorebombardment served in five landing assaults, Casablanca, Sicily, Salerno, Anzio and Southern France, receiving a star for each. As her last Gunnery Officer for heavy shore bombardment at Southern France, I can attest that Edison was regunned three times and likely fired as many (or more) 5"38 cal. shells as any destroyer in World War II.

Edison's armament configuration changed rapidly after launch at Federal Shipbuilding & Drydock, Kearny NJ, November 1940

In our page entitled "U.S. Military Draft and Pearl Harbor" seawar1.htm , the photo of the USS Edison underway showed no main battery gun mounts at all. Launched in late November 1940 at Federal Shipbuilding and Drydock in Kearny, New Jersey, Edison was commissioned at the Brooklyn Navy Yard on 31 January 1941. She made short shake down cruises in February and March 1941 and returned to the Brooklyn Navy Yard for a six weeks installation of her main battery of five 5"/38 cal. DP guns.

Edison had five war paint "appearances" during her active war life. The first was plain gray. Then came a North Atlantic wavy camouflage paint job, followed by one of Mediterranean medium gray over dark blue. Her fourth, and most used, was a Mediterranean/North Atlantic "zigzag" camouflage. She finished her duty in the Pacific painted in the dark gray used there.

The number of different Edison "appearances" has not been restricted to wartime paint jobs. The Edison underway photos reveal three different main battery configurations, namely no guns, five guns, and four guns, in that order. In a letter which appeared in the Edison News' 20th issue in September 1971, her first Commanding Officer, (LCDR USN, while he was Edison's skipper and later, Adm. Albert C. Murdaugh USN (Ret.), provided information not available in official records.

"I was ordered to the Edison from duty at the Naval Gun Factory in Washington, DC. The first thing I did, on getting the word unofficially, was to hand-pick a main battery. Meanwhile, the Federal Shipbuilding Corporation, seeing a war coming on and wishing to establish a good performance reputation for the sake of future contracts, decided to deliver the Edison six weeks ahead of schedule. A classmate who was superintending construction at Kearny, tipped me off. I hastened to get the guns shipped and found, to my consternation, that F.D.R. had given them to one of the small British AA cruisers in the Mediterranean, who were then hard-pressed. Next, I went to BuPers (Bureau of Naval Personnel), who simply didn't believe me. (that Edison would be ready early) Finally, I persuaded them to look into it, and they ended up by ordering the Edison detail (officers and men who would put the ship into commission), which I had just begun to assemble. Some of the men arrived for commissioning with only three weeks of boot camp. Fortunately, in desperation I at last reached a sympathetic ear at OpNav (Naval Operations). They, in effect, told us (the ship and its crew) to go and get lost for six weeks. Things couldn't have worked out better. The recruits learned far more aboard ship than they would have at Newport (the Navy's torpedo station). We were able to concentrate on basics and when the guns were finally installed, gunnery technique was quickly mastered, as the record shows."

"On the question about the number on the bridge wings in the old photo (the "old" photo he referred to is the one which follows), my recollection is somewhat hazy after so many years. The circumstances were somewhat as follows. Few people, except specialized historians, now know that on 1 September 1941, Admiral King (Ernest J. King, Commander-in-Chief Atlantic, later Chief of Naval Operations) issued an operation plan setting up regular convoy operations in the North Atlantic. Presumably, to delay full realization by the Germans of what was happening, orders were issued to paint out bow numbers and put them on the bridge wing, like the British and Canadians. Many ships were just too busy at the time to get around to it. The order reached us in the Navy Yard, where compliance was easy. After Pearl Harbor, the numbers were put back in the accustomed place."

This next picture with guns installed shows Edison still without "war paint". The five 5" 38 cal. guns installed at the Brooklyn Navy Yard after her launch and commissioning are shown in this photo.(Print halftones do not reproduce well)

The 5"/38 cal. gun on the forward edge of the after deckhouse behind the second stack was removed soon after this picture was taken as compensation for other topside weight to be added. Edison's war history was compiled with four 5"/ 38 cal DP guns as her main battery. The high superstructure on the after deck-house would be removed at this same time and a lower profile 36-inch searchlight inserted in its place. It could reasonably be assumed that this high superstructure aft had been originally intended to give the after conning officer a high visibility platform in situations where the bridge, pilot house and forward conning structure had become inoperable due, for example, to battle damage. But, topside weight considerations eventually dominated all modification decisions. U.S. Navy destroyers had capsized in storms. Boards of inquiry decided that one source of concern was too small a margin of metacentric height (a linear measurement representing the difference between the center of gravity and the center of buoyancy). In a ship's roll, a sufficiently positive measure of metacentric height provides the lever arm in the restoring moment to bring the ship back level. Later additions to Edison and her class were two 40 mm Bofors AA gun mounts to complement the 20 mm Oerlikon guns already installed. Torpedo directors were also added, one on each wing of the bridge. The cylindrical object on the after quintuple torpedo tube mount aft of the second stack just forward of the after deckhouse was also removed.

USS Edison DD439; Build, Commissioning and Outfitting Data

Keel laid 18 March 1940 at Federal Shipbuilding and Dry Dock, Kearny, New Jersey. Built alongside her sister ship, USS Ericsson DD440. Launched 23 Nov. 1940. Named for Thomas Alva Edison, famed US inventor. His widow wielded the champagne bottle. Governor Charles Edison of New Jersey, his son, was present at commissioning. Ship construction details were 1630 tons displacement, 348 feet at waterline, 36 foot beam, just under 12 foot draft. There were two Westinghouse, 25,000 shaft horsepower, steam turbines, driven by four Babcock & Wilcox triple drum boilers, rated 600 psi, 750 deg. F. Rated top speed was 37 knots. She was of the Benson/Livermore class, two stacks with a foc'sle deck. Commissioned 31 Jan. 1941 at the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

Her armament: Four 5"/38 cal dual purpose guns controlled by General Electric Mk 37 (amplidyne drive) Director, Sperry stable element (gyro), and Ford Mk 1(mechanical, analog) Computer; two quad mount 40 mm AA guns; eight single 20 mm AA guns.; ten 21-inch torpedoes in two quintuple mounts; two racks (tilted, for roll off) of 600 pound depth charges on stern, and 6 K-guns for 300 pound depth charges, three on each side from midships aft. Edison's complement varied from seven officers and about 100 men at commissioning in 1941, to 24 officers and over 250 enlisted men when the U.S. finally got its military manpower at war strength in 1944. Sonar and radar: High frequency sonar transmitter and echo detector in a faired dome on the hull. SC long range aircraft detection radar, antenna on main mast high.. FD fire control radar, with antenna on top of MK 37 Gun Director, azimuth controlled by training director, elevation control independent of director. Used "lobe switching". Not very effective. When the number of ship's officers became too large for the number of bunks in the officer's quarters, I was shifted to Division Commander's cabin (we had no DivCom aboard) and slept next to the FD radar magnetron. I was directed to wear a bite-wing (dental) x-ray patch pinned to my undershirt. Good intentions for sure, but no one ever checked it to see if radiation had affected me. Also, the spare magnetron for the FD radar ("maggie") was stored under the FD radar cabinet and only Holmes Bridges, Edison's Chief Radioman, who had gone to the Bellevue Laboratories Radar School in Washington DC, knew it was there. But, I discovered it. I have not told anyone until writing these lines. Radar was very secret in early WW II. In late 1942, after the North African invasion, the Navy Yard installed the Raytheon SG radar. The SG radar's PPI-Plan Position Indicator-a large oscilloscope with the main glass up and the gun down, was installed in the pilot house next to the binnacle. The SG radar's horizontally rotating antenna was installed on the main mast under the fixed SC radar antenna. More about how the huge technology advance of the SG radar meant changed everything comes in later chapters. SG radar was one of a very elite number of U.S. wartime tools that made the crucial difference in WW II. We had it. They did not.

Not exactly armament, but important in some enemy action situations, were the smoke generators. These were used on several occasions, one of which was a surprising close call for Edison at Ventimiglia along the northern Mediterranean coast of Italy. Look for a description in a future chapter.

In her total period of service, 940 officers and men served aboard Edison. Eight enlisted men served the entire period of just over five years, from commissioning to decommissioning. (This statistic on the total number of personnel who served on Edison is not found in official Navy records, but was compiled by Edison sailor Robert Cloyd in 1971.)

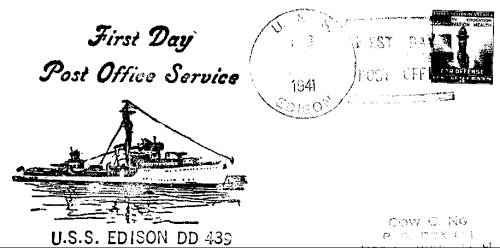

One of the longtime customs of ship commissioning is recogntion by the United States Postal Service, with a stamped envelope. These are prized by collectors. One collector, who likely found about my connection with the USS Edison, DD-439, when the former skipper of the USS Wilkes, DD-441, who was living in or near Newport RI graciously agreed to hand carry a copy of "Joining the War at Sea 1939-1945," to the Navy War College as a gift to their library, generously sent me the Post Office's recognition of the brand new USS Edison as a new ship in the U.S. Navy. The two stack Livermore class destroyers had not yet made it into the Postoffice's art collection so a single stacker of Pres. Roosevelt's Navy build plan of 1935 served in its stead.

The destroyer USS Edison has just been launched from her building ways at Federal Shipbuilding and Drydock in New Jersey. The U.S. Postal Service has taken note of her first day of postal service. That occurred late in 1941 but the date is obscured. This canceled envelope was personally delivered to Capt. Franklyn E. Dailey Jr. USNR (Ret) by Captain Herbert Rommel USN who had been skipper of the USS Wilkes, DD-441, which went to sea in World War II in DesRon 13, with the Edison and seven other destroyers. The actual "handing over' of this envelope occurred at Fall River, Massachusetts, where Edison shipmates were enjoying a reunion aboard USS Massachusetts, the battleship that both Edison and Wilkes served with at the Battle for Casablanca in November 1942.

Service Summary

Edison's main service was in the Atlantic and Mediterranean from 1941-1945. After a brief period in the Far East in the last half of 1945, Edison returned to Charleston, South Carolina in early 1946. She was decommissioned there on 18 May 1946. Her last years were spent as part of the inactive "mothball" fleet in the Philadelphia Navy Yard. In June 1965, Edison along with Ericsson (440), and Woolsey (437) were sold for scrap. Edison was sold to Lipsett of New Jersey for $87,000. She began and ended her life in New Jersey.

The Shipyard

Let me add a personal note. As the ship's welfare officer for most of 1942 and 1943, I handled large, semi-annual, money contributions to the ship's welfare fund from the workers at Federal Shipbuilding and Dry Dock who had built Edison. These funds were used for ship's parties and other "worthy" uses. I can never forget the unparalleled generosity of the shipyard personnel who built an extraordinarily seaworthy ship. If any them survive to read this, let them know that their efforts and financial generosity were matched by a dedicated crew, mostly reservists and draftees, who fought the Edison brilliantly against an unforgiving sea and a desperate enemy.

The Ship's Armament Usage

The official Edison launch data was covered above. Usage summaries are offered here which will help the reader anticipate some of the engagement activity in which the ship participated. This activity will be told in future chapters. In this way, the later pages can emphasize the flow of the action while the reader will already have an overall picture of the ship's life cycle.

The torpedo battery: The World War II destroyer evolved from the pre-war WW I torpedo boat. In WW I these torpedo boats evolved over a series of class building upgrades into destroyers. In the sea war in the Pacific in WW II, a few division or squadron-strength destroyer torpedo attacks were pressed home. No mass torpedo attacks were recorded by US destroyers in the Atlantic or Mediterranean theaters. While the Edison fired torpedoes in training, she never fired one in action against an enemy. Interestingly, the Edison was part of the destroyer detachment which screened the battleship USS Iowa with President Franklin D. Roosevelt aboard when he made the famous trip that culminated in the Cairo meetings with Chiang Kai-shek of China and Prime Minister Churchill. Edison was part of the Mediterranean screen from Gibraltar east. A different screen brought Iowa from US waters to Gibraltar. It was during that part of the trip on 14 November 1943, that the USS William D. Porter (a destroyer later sunk in a Pacific battle) fired a torpedo, mistakenly, at the Iowa. Porter was conducting a training exercise and the crew in training made the mistake of choosing Iowa as the training target. The destroyer then compounded the mistake by actually firing the torpedo. The crew likely did not know what "cargo" the Iowa carried. According to one newspaper story, reprinted in the Edison News, Iowa took evasive action and the torpedo exploded in her wake. Training exercises took an enormous human toll in the period of the author's tour aboard Edison and some situations will be cited later in our story.

The secondary AA batteries, 20mm and 40mm guns: Ring sights were used in early engagements. Later a MK 14 gunsight was added to the 20mm guns and included in a MK 51 director for the 40mm guns. The guns themselves worked fine. Profiiciency with the MK 14 gunsights came slowly and in many action firing situations, personnel fell back on the old ring sights. One 40mm "premature in the breech" due to a tracer ignition in a lot of Triumph (manufacturer) shells caused eye damage to a young Gunner's Mate. The author (then the Gunnery Officer) had just received an urgent message warning of this possibility in a given lot of 40mm shells and was consulting the magazine inventory when the ship went to General Quarters against air attack. It was then that the accident occurred. Edison, unfortunately, had that lot of 40mm shells aboard. The failure specifics were precisely as predicted. Also, Edison's first quad 40mm gun mounts had to be replaced because the drives were friction-coupled and salt water quickly decomposed the friction surfaces (sandpaper). Pouring a quart of oil into a hole marked "Oil Here" did not help. The later hydraulic drives worked fine. Edison's secondary AA batteries were in action frequently. German planes did not press attacks home like the Japanese so leading the enemy aircraft sufficiently in azimuth was usually the key to fire control success.

(While some formal training was given for torpedoes and for the light AA guns, most of this training was what the ship itself could work in on its own. Priority for training, with full exercises scheduled, was given to ASW and to AA and shore bombardment for the main battery 5"/38 cal guns. For the Edison, which seemed always to be selected for close-in support of the amphibious forces making landings, priority was given to shore bombardment.)

Depth charges: Used frequently against sonar targets which were classified by the sonar operator as probable submarines. Edison trained several times during each watch in setting various "patterns" for depth charge explosions. These drills came without warning to the watch standers. Setting a given pattern in less than 30 seconds was an objective. For the crew, this involved going from a lookout watch station down to the main deck, often in rough weather, and getting enough illumination and "feel, to make the setting, if at night. Any setting other than "safe" armed the charge, causing it to go off at a given, "set", depth. Edison SOP (standard operating procedure) was to leave charges on "safe" at all times except when attacking a suspected submarine. The reasons for the SOP will become clear in one of the chapters. When conditions permitted, Edison also trained with other destroyers in "creeping attacks", where one destroyer pinged with its sonar and barely kept steerage way in order to provide minimum sea noise, while the other did not ping but was vectored in by the pinging destroyer in a creeping movement to get over the target for release of depth charges. The British came up with this scheme which provided better sonar performance and kept the sub puzzled about what was going on.

Main battery, 5"/38 cal. Dual Purpose guns: Edison had to be re-gunned (new barrels) twice while the author was aboard. Very likely the ship was near the top in all US Navy WW II destroyers in rounds fired per 5" gun barrel. A gun barrel could "wear out" in several hundred rounds, with extensive firing intensively concentrated in relatively short time periods causing the most wear. The only other "wearing" components were the "bloomers" which (almost)sealed the aperture in which the gun moved in elevation in the mount, against the salt water elements. The bloomers would simply burn up during concentrated periods of fire. The early leather bloomers were replaced with canvas when the Navy figured out that bloomers had become a "consumable". This battery of guns, director, computer and when needed, stable element (gyro), experienced near flawless system performance. The Chief Gunner's Mate (Kerns) and Chief Fire Controlman (Jackson) and their men deserved much of the credit. These gun mounts had hydraulic drives. Tiny air bubbles in the hydraulic fluid were an occasional cause for a given gun mount to "hunt" in azimuth or elevation. This took some maintenance crew nursing, but could be dealt with. The extremely reliable General Electric MK 37 Director had an amplidyne drive. The director, mounted above the flying bridge, was up and clear of most of the sea spray. (Number 1 Gun mount up on foc'sle often would be bashed in due to heavy seas. One way we learned to minimize this damage was to leave the # 1 gun trained out to the starboard bow, so the sea did not have a flat surface to pound.) The range finder in the main director had both coincidence and stereo options. Chief Fire Controlman Jackson had sharply curved eyeballs and I often thought he did not need the rangefinder's stereo feature at all; he certainly used those optics with deadly effectiveness. In AA shooting he would open up in range right on the enemy plane and usually with one small azimuth or elevation spot (correction) would be able to call for "rapid fire". The Sperry gyro and the Ford computer allowed the ship to go into "automatic" fire with just small spots needed for correction. After the Raytheon SG radar was put aboard, the Skipper would on occasion have the shipfitters make a floating metal target to anchor near a beach whose shallow gradient did not give good SG radar echoes. Then, shore bombardment could proceed in "automatic" with reference to this marker, again with just small spots radioed from shore fire control parties (SFCPs). The computer would simply take into account the ship's movement and grind out the "problem". The 5" battery used "semi-fixed" ammunition, a shell, and a brass cylinder which held the "powder" propellant. These had to be mated in the gun's loading tray and a rammer pushed them "home" and then the breech could be closed. An electric plus impact primer was in the brass cartridge. On the port side about amidships was a 5" gun "loading machine". It was used constantly to train crews. Edison could fire with a Condition ONE gun crew, the battle station situation, or with a ready gun crew , Condition THREE, or a watch and watch crew, Condition TWO. These different gun crew personnel situations required a lot of men to know a a variety of jobs in firing the guns. On the loading machine, for one, two or three minute periods, the crew objective was 20 rounds per gun per minute! Edison crews achieved those rates in combat. The Germans likened our effective rate of fire to machine guns with large shells. The ship usually carried some star shells for night illumination, some armor piercing shells for special targets, some 'influence" or "proximity" shells essentially for AA, and some white phosphorus shells to help spotters move our fire to the target. We used all of these on appropriate occasions. The proximity shells, with so-called VT fuses, came with so many restrictions to their use (so the enemy would not capture a dud and learn the secrets of construction) that we never used them in action situations on the Edison while I was aboard. The preponderance of shells aboard were referred to as High Capacity or HC. These could be fired at ground or air targets. There was a nose ring time fuze, set in the fuze setting hoist, which derived its setting remotely and automatically from the computer's solution. This was the primary fuze for AA fire and also for anti-personnel fire on ground targets when seeking an above-ground detonation. There was a nose impact fuze. And there was a base detonating fuze. In other words, fuzing was redundant. After all the work to deliver the shell to a target vicinity, if the most optimum detonation did not occur, the backup objective was to make "something" occur. I was aboard when two sets of gun barrels were worn out and I do not recall a malfunction of this battery during action. If one held a contest to name the most effective piece of conventional ordnance in WW II, my nomination would be the 5"/38 cal. gun system in the US Navy.

The Edison's Engineering Plant Usage

I was involved directly in ordnance aboard the Edison and the amount of detail on ordnance furnished in this Chapter reflects that. Of necessity, officers specialized in wartime. I rarely got into the engineering spaces. Many below-decks personnel had to actually be ordered to come topside when we were in port. The sparseness of detail on engineering here reflects those wartime realities. Also, deck logs are the officially archived logs of a ship. Little information has been preserved of the record of Edison's power plant for her active years.

I can say that the Edison power plant was always on line when it was needed. It never failed. The conning officers, and I was one, often called for tremendous acceleration, well beyond the printed curves for increasing speed. The Captain at his General Quarters battle station with the con was occasionally warned by the engineering officer below, of the dire results if we changed speeds so fast, but we certainly always got the desired result. Sometimes the impact of a shell landing close aboard silenced the protests from below. Yes, we lost "suction" occasionally, but Edison's corrective procedures restored the situation immediately. These lines are written with gratitude, if not with a complete grasp of what these men contributed.

Engine Miles Steamed

| Year | Nautical Miles |

| 1941 | 43,769 |

| 1942 | 78,680 |

| 1943 | 60,875 |

| 1944 | 52,855 |

| 1945 | 51,979 |

| 1946 | 4,973 |

| Total | 293,131 |

The peak year 1942 reflects a period in which Edison repeatedly operated in escort of convoy duty. In 1943 and 1944, the convoy duty was restricted to escorting combat forces to an amphibious landing or coming back from one, and the Edison's "steaming" was prioritized toward actual landings and shore gun fire support. There were fewer trips back and forth across the Atlantic and Edison was actually home-ported at Mers-el-Kebir, Algeria, near Oran, on the south shore of the Mediterranean.

Fundamental maintenance went to the boilers which had to be "re-bricked" after extensive steaming or more frequently if there had been emergency accelerations or decelerations. Printed schedules were followed for bringing boilers on line in carefully timed sequences and shafts were slowly rotated before getting underway to make sure that the turbine-propeller systems was working properly. Edison's "black gang", as the propulsion system personnel had become known from coal-fired days, were very conservative and always let the bridge know when the (getting) underway "special sea details" of personnel in the pilot house would try to "speed things up". Edison was fueled by bunker fuel #6 with a little Diesel laced in to help keep the innards clean. Fueling at sea in bad weather was an often risky all-hands evolution. This will come up in the later chapters. One skipper of a US cruiser was relieved on the spot by the Task Force Commander because the cruiser CO was so reluctant to take on oil from a tanker in rough seas.

"Skipper" and "CPO" Usage.

This might seem an unusual category to include in a materiel-emphasized portion of this ship's story. The point of view is helpful in setting forth another toll of war. That toll is on the lives of men who are not killed or even wounded n action, but on whose lives the war took a big toll. It applies to both officer and enlisted personnel, and it relates to the age of persons enduring periods of intense vigilance and conflict. Generally speaking, the young endured physically much better than the middle-aged. This does not mean that any age bracket acquitted their assigned responsibility better than any other but reflects my own observations on what happened to these groups after the war.

The plank-owner detail of the Edison included a high percentage of experienced officers and senior petty officers. The term "high" is used in comparison with ship's company at later periods in the war. My observations in this matter are anecdotal. I did not keep statistics. In the years following WW II, I subscribed to Shipmate, a magazine for alumni of the US Naval Academy, and to an Annual Report of the Navy Mutual Aid Society, an insurer of Naval personnel, mostly officers but also of some higher ratings in the enlisted category. Both sources published death notices. My observations were that personnel of "middle age" (in the 1940s, men in their 40s were regarded as on the threshold of middle age) who had been actively engaged in combat roles in the Atlantic or Pacific theatres often died relatively soon after the war's end.

In the next table, a list of the Edison's Commanding Officers, will illustrate how a rapidly expanding wartime Navy forced down the age of its combat personnel. As time went on, the younger men were not less experienced. Experience had simply come to them faster.

Edison Skippers

| Name/ | Naval Academy Class/ | Took Command | /At age |

| LCDR A.C. Murdaugh/ | 1922 | 31 Jan. 1941 | 40 |

| LCDR W.R. Headden/ | 1925 | 1 Mar. 1942 | 38 |

| LCDR H.A. Pearce/ | 1931 | 24 Feb. 1943 | 33 |

| LCDR W.J. Caspari/ | 1940 | 1 Apr. 1945 | 26 |

Awards

Edison Combat Awards: a total of six battle stars were authorized on the European-African-Middle Eastern Area Service Medal for participating in these operations:

1 Star/Escort, ASW and special operations, Convoy ON-67; 21-26 Feb. 1942

1 Star/North African Occupation

Actions off Casablanca; 8 November 1942

Algeria-Morocco Landings; 8-11 November 1942

1 Star/Sicilian Occupation, 9-15 July, 28 July-17 August 1943

1 Star/Salerno Landings; 9-21 Sept. 1943

1 Star/West Coast of Italy Operations

Anzio-Nettuno Advanced Landings; 22-31 Jan. 1944, 2-5 Feb. 1944, and 8-11 Feb. 1944

1 Star/Invasion of Southern France; 15 August to 25 Sept. 1944

The USS Edison also earned the Navy Occupation Service Medal, Asia for the periods from 2-26 Sept. 1945 and 20 Oct. to 4 Nov. 1945.

I was not aboard for the last Medal, nor did I earn the star awarded for work in Convoy ON-67 because I had not yet reported to the ship.

The new 457-page Fourth Edition 2009 of the book, "Joining the War at Sea 1939-1945," is now available. The 44-page Index by European scholar Pieter Graf adds valuable reference pages.

A separate free 8-page index of 300 ships the Edison served with or for in WW II has been developed by Mark Henshaw. Write Dailey International Publishers, 500 Laurel Oaks Lane, Alpharetta, GA 30004, or e-mail franklyn21@earthlink.net for a free copy of this index and a companion index of aviation and army units mentioned in the book.

Finally, obscured in the tabulation of this kind of data, it needs to be noted that while the Edison was a "small boy", a term applied to destroyers by Pacific Admirals in command of large carrier task forces, the 940 men who served throughout the life of Edison related to: nearly 2,000 parents, hundreds of wives and children, and countless neighbors; this extended family made up the 'home front", checking V-mails and public news sources every day to obtain wholly insufficient lines about what "their boys" were doing. I have a few fragments of these saved and will offer them at appropriate points. Many are in the book.

The book I have written cover's war history of the USS Edison DD-439 which served in early convoy duty in World War II (before Pearl Harbor) served as front line fire support in five invasions, Casablanca, Sicily, Salerno, Anzio and Southern France. My own service aboard ended when I was Edison's Gunnery Officer for the Southern France invasion and shortly thereaafter was detached to go to flight training at Ottumwa, Iowa. The book is not a ship's history but a war history. Here we will attend to some of the personal information that would have been found in a ship's history. I will be aided by folks who served on Edison when she went to the Pacific war zone in 1945.

Here is a photo taken during an Edison ship's party at the Ritz Carlton Hotel in New York City while Edison was still serving in the Atlantic Fleet and in the 8th Fleet in the Mediterranean. (Also part of DesMed.)

.

.

Part II. Edison in the Pacific (and finally in a Reserve Fleet at Charleston, SC)

Next you will see the officer group that took Edison to the Pacific war in 1945. While Edison's enlisted complement did not change drastically, her officer complement, limited to eight when I relieved J.J. Jackson Jr. in July 1942, ratcheted up to 22 when war demand of 'watch and watch' or '4 on and 4 off' at the height of the Mediterranean Sea War and visiting officers slept on the transoms (lengthy settees) in the wardroom while aboard. I was lucky at the fast pace of rank in those days because I got the Division Commander's cabin before it was eliminated by the CIC. (I slept next to the FD radar transmitter and its magnetron ('maggie') and wore, on orders, dental x-ray film on my chest to see if I was getting too much 'radiation.' Only problem I was detached and no one ever 'read' the film and finally I threw it away.)

Here below, the group of officers who served on Edison in the Pacific war and some of its aftermath, courtesy of Russ Rossell, one of those pictured.. The officer count is down to 17.

"The names in the picture are:

Standing: RABEN, TANNER, OLIVER, CAPT. CASPARI, OUELLETTE, LINDSAY.

Kneeling: DR. PYLE, PEARSON, TYSON, HOSTVEDT, WAECHTER, SHEPHERD.

Sitting: ROSSELL, KINNEY, DAVIS, INGALLS, WARD.

"I'm almost positive the picture was taken in Manilla, Phillipine Island. There were a lot of sunken ships in the harbor and we were anchored there. We'd take the Captain's Gig to go to the fleet landing.

You asked me one time who the XO was and it was Oliver. After he was transferred, Marvin Tanner was the XO

/s/ Russ Rossell"

Those still with us, and whose eyes are still sharp, can find officers who served in both oceans. I always hope that family members will find these web pages and add to our identification knowledge. Erik Hostvedt, son of Al Hostvedt, did just that, and with the help of Russ Rossell and Jean Whetstine, the foregoong addition to this page was made possible on July 22, 2011, or in Navy lingo, 22 July, 2011. (corrections and improvements August 9, 2011 and again on January 31, 2012) Now to a more comprehensive tale of the USS Edison DD-439 after she left the Mediterranean.

The book, "Joining the War at Sea 1939-1945," (see cover photo at beginning of this page) include WW II amphibious landings at Casablanca, Sicily, Salerno, Anzio and Southern France. The USS Edison DD-439, the centerpiece platform for enemy action in the book, was, by 1944 primarily a gunfire support destroyer, only occasionally drawn back into convoy protection duties. All of the destroyers in this Mediterranean theatre were part of DesMed, with ComDesMed, who also Commander Destroyers 8th Fleet, mostly based on the repair ship, USS Vulcan AR-5. That ship spent that part of World War II in Oran, Algeria, tied up alongside the dock at Mers El Kebir. When fire support for troops ashore at the last major landing at Southern France was no longer needed, and VE Day was in sight for our Armies in Europe, the U.S. Navy ordered every available ship that could perform war missions to the Pacific. Most of the working machinery on the DesMed destroyers had been pretty well beaten up, especially the guns, the engines and boilers. East Coast shipyards were again pressed into heavy duty service to get these combat ships restored to war readiness and then get them through the Panama Canal to join amphibious support destroyers in the Pacific. These Navy Yard refurbishments took time, so many of the officers and enlisted men were detached to ships ready to go; a change in Edison's manpower complement took place.

One of the new officers ordered to the USS Edison was Ensign Russ Rossell. He takes up the story of the USS Edison, DD-439, as she begins what would be her final wartime cruises in the Pacific war theatre. Russ's story begins here:

"Prior to being ordered to the U.S.S.EDISON DD-439, I was stationed in the Norfolk, VA Navy Yard, attending Destroyer Officers Training School, from March until June 1945. It was during that period that President Franklyn Delano Roosevelt passed, and traditional honors were observed at Navy Yards for a thirty day period of mourning. It was a sad time. We all knew the end of the war in Europe was only months away. How fitting it would have been if FDR, our former Commander in Chief, who led us during the war, had known the feeling of thanksgiving, joy and tears that we as a nation all felt, when we learned the war in Europe was over. It was now time to finish the job, and defeat the Japanese in the Pacific.

"So it was in June 1945, that I received my orders to proceed to the U.S.S. Edison DD-439, which had served with distinction for 23 months in the Mediterranean, including fire support for the invasions of Salerno, Italy on 9 September1943 as well as that of Southern France on 15 August 1944. The Edison was now en route to San Diego from the Atlantic, via the Panama Canal. I arrived on the West Coast on 3 July 1945 and reported to the Commanding Officer, Naval Operating Base, San Diego, to await the arrival of the Edison. Upon her arrival I reported aboard to the Commanding Officer, LtCdr. W. J. Caspari USN., on 6 July. I was assigned to the Intelligence Division, with duties in Combat Information Center (CIC). The ship had struck a whale and damaged its underwater sonar dome requiring the ship to go to dry dock for repairs. Also one of the main engines was found to be inoperative and had to be replaced as well. Once repairs were completed trial runs were made and the main bearing on the starboard shaft would overheat. This was repaired to the point that on 27 July, the Captain and Edison set sail independently for Pearl Harbor, T.H., arriving 2 August.

"As soon as we left port, the "bridge gang" became very interested in the flash cards for the Japanese aircraft. Even studied them while waiting in the chow line. Prior to that, while in port, after lunch, I would take them over to Audio Visual Aids for the same recognition training, now with lights dimmed. Some would take the opportunity to rest their eyes and weary bones. (The U.S. Navy WWII ships and aircraft recognition training slide set-35mm glass slides-are prominent on this website in the www.daileyint.com/wwii folder.)

"We were part of a Task Force which was to invade Japan. Before Edison's crew could finish our specialized training in fire support for the landings, we received information that the A-Bomb had been dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The Japanese government surrendered on 15 August 1945, and our Operation Orders were changed from an invasion, to an occupation of Japan.

"On 1 September 1945, the Edison, acting as one of many escorts, departed Pearl Harbor, for Japan. While en route to Saipan, one of the Troop Transports, the USS. Dawson, APA-79, encountered engine problems and as a result could not keep up with the Task Force. The Edison was assigned to stay with the Dawson as an escort. On 12 September around 1750, I was waiting for my relief in CIC when we heard Man Overboard over the TBS radio! It was the Dawson. Immediately the Radar Operators turned on the DRT (Dead Reckoning Tracer) and got a radar bearing and range on the Dawson and marked her position. From that point they calculated approximately the site, the sea position, where the incident had occurred. Edison then proceeded to make courses and speeds to the site to begin a planned search pattern. Meanwhile, our ships crew, under Chief Bos'ns Mate Ducharme, were manning the rails to try and pick a man in the water out visually. At the time of the Man Overboard announcement, it had started to rain and continued to rain quite heavily at times, with increased wind and waves, making visibility very difficult. As time wore on, and twilight advanced, the search pattern continued to shrink. We were all concerned that our man would not be found. (Chief Boatswain's Mate Ducharme is pictured in the book referenced at the beginning, and was one of six of the longest serving Edison shipmates when this search occurred.)

"We were on our last leg of the search, some three hours later, when the man overboard was sighted off our port side, swimming in his skivey shorts. It was now 2103. Other than a slight scrape on one of his arms, he was fine and was returned to his ship when we arrived in Saipan. The Captain of the Dawson thanked us and sent over several gallons of ice cream for our crew. (This was a remarkable recovery. Most men overboard in the open sea are never recovered.)

"Saipan! I had never seen so many ships in one place, at one time. Hundreds of warships, troop transports, and logistic ships, oil tankers, reefers, ammo ships, all bound for one place, Japan.

Back to sea, we arrived off the Japanese Islands and proceeded to the inland sea of Japan, and entered Sasebo in the Hiro-Wan area on 22 September 1945. I'll never forget the floating corpses of Japanese men dressed in ceremonial white robes, who had committed Hara-Kiri, before we entered the harbor.

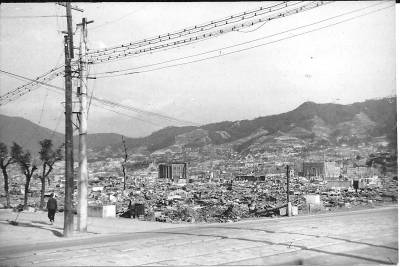

"After the occupational landings had taken place, on 24 September 1945, Edison proceeded to Nagasaki with Rear Admiral Riefsnider and Major General Schmidt as passengers. As we slowly entered the port of Nagasaki, the first thing I saw was the vast devastation of the whole area caused by the Atom Bomb. Along the waterfront were the skeletal remains of steel building supports, blackened, twisted and distorted as if by some huge unseen force. As we got closer to the center of the city, only piles of rubble remained where once stood a thriving city of people who had lived and worked in the Shipyards. The rubble had been cleared from some of the streets and there were telephone poles still standing, also trees bare of all leaves seared by the intense heat and blast of the bomb. Total destruction of everything within a 3 mile radius of ground zero.

Nagasaki 1945, after the Bomb. (courtesy, Russ Rossell, officer on USS Edison, DD-439: September 1945 port visit)

Nagasaki, after the Bomb (courtesy, Russ Rossell, officer on USS Edison DD-439 during ship's Sept. 1945 port visit)

Nagasaki, after the Bomb (courtesy, Russ Rossell, officer on USS Edison DD-439 during ship's Sept. 1945 port visit)

USS Edison, DD-439, departing view, Nagasaki, Sept. 1945. courtesy, Russ Rossell

Russ Rossell offers a deep reflection here, in italics. "In retrospect. some people feel it was wrong to have used the Atom Bomb, against a civilian population, much the same as people who criticize the massive bombing raids in Europe and England. I know that because of it, we did not have to invade the Japanese homeland, which was heavily fortified to repel any invasion attempt. Its mountainous terrain and reverse slopes made for a very long and protracted invasion, with the potential of thousands of casualties on both sides. In my opinion the decision was right at the time. Just witness the losses at Okinawa. There are legions of gallant men still alive today, who were willing to give up their lives to win the war in Japan, begun 7 December 1941 by an unprovoked attack on Pearl Harbor by the Japanese Navy."

" On 25 September 1945 the Edison left Sasebo for Manila where she arrived on 30 September. The harbor of Manila was strewn with the sunken hulls of many freighters as we entered what was once the "Pearl of the Pacific." We anchored in the harbor during our brief stay. The result of the Japanese occupation was visible everywhere. Most every building still standing was either partially demolished or battle scarred by enemy or defending fire.

"I was on Shore Patrol there and patrolled an area that included the last bars in town before the fleet landing. Lots of fun! On 8 October we left Manila with the USS Niblack, DD-424, forTalomo, Mindanao, PI. where we arrived about 10 October. We anchored in Davao Gulf and were there for 5 days. I took the men over to the beach for a picnic and to play some softball. Of course we had some cold beer.

"While there we needed to do some paint work as the ship was getting a little rusty. We went to one of the transports there to bum some paint but the only way we could get paint was to trade our beer as they didn't have any. Needless to say we kept the beer. I remember going down the main street of Davao and the biggest store was a Singer Sewing Machine store, with a big Capital Red "S" logo in the window. The Japanese had been there as well and had an air field not too far out of town. The skeletons of Japanese aircraft were abundant around the area. We then assumed duties as escorting vessels for T.G. 54.13 which consisted of Transport Squadron FOURTEEN and the 27th Infantry Division.

"The Task Group sailed from Talomo on 15 October for the Kure-Hiro Wan Area, arriving 21 October. The ship remained in this area until 30 October when it proceeded to Nagoya, Honshu. I might add that during that period we encountered a Typhoon which was so strong, that it lifted the Depth Charges off the stern racks and we had them rolling around on the fantail. Fortunately, our men were able to go topside and secure them under very difficult circumstances. We then proceeded to Adak, Aleutians, arriving on 8 November. On 16 November the EDISON sailed with passengers for Seattle, Washington via Dutch Harbor.

"The trip was interesting in that the weather was rain, rain and more rain. To navigate we used dead reckoning and information we could glean from our LORAN gear. I was extending the base line extensions to get our "fix". It seemed to work fine as we were able to pick up Seattle on our radar and used that to get close enough to use visual aids for navigation. While in Seattle, I learned to run both an LCVP and an LSM. The latter having two diesel engines, one port and the other starboard. It was good experience that I later used to good advantage. We returned to Adak on 3 December, 1945.

"On 13 December, the EDISON was underway from Adak and proceeded to a point at 165 degrees E Longitude,. 43 degrees North Latitude, to relieve the USS Plunkett, DD-431, on weather patrol. The Fleet Tug that had been assigned to that duty left for repairs.. After 10 days of going around in a circle, 60 miles in diameter, and reporting the weather every six hours, the ship was relieved and proceeded to Adak, arriving 24 December.

"I might add that during those 10 days we were constantly having to de-ice the ship as the water from the sea and rain formed ice on the standing rigging as well as the superstructure . We would roll 52 degrees to starboard and then 52 degrees to port and this continued for most of our stay. Those that weren't sea sick, ate a lot of sandwiches. Also I remember we had two Christmas Eves that year as we crossed the International Date Line.

"That same day, 24 December, with Naval and Marine personnel aboard, the Edison was underway for San Francisco, Calif., arriving 30 December. As the Mess Treasurer, I had nice greasy pork chops served as our first meal underway. Needless to say our passengers for some reason got seasick and with one exception hardly ate anything for the rest of the voyage. The exception was a Marine Officer who ate every meal and then got sick, Since I was getting paid for their meals whether they ate or not, he said he was going to get his money's worth. And he did. Of course with the surplus in funds we were able to have very good meals at no increase in the monthly bill when we got back to the States with fresh vegetables, milk, and other fare not available at sea. At this time the ship was traveling independently.

"After a 3 day period, with liberty for all hands in San Francisco, the Edison with five other ships of DesRon 22 (formerly DesRon 13) proceeded to the Canal Zone at Balboa for transit to the Atlantic Ocean; This was my first and only voyage through the Panama Canal and it was spectacular. Going from lock to lock and having the water fill each lock to raise us to the next level until we got to Miraflores Lake, and thence on through the rest of the canal which can last from 8 to 10 hours to Colon, completing the transit on 14 January 1945. From there, the formation proceeded to Charleston, S.C., to report to ComCharlesGroup for laying up in the Inactive Fleet. Upon completion of a period of availability, the Edison was de-commissioned and thus completed its life as a U.S. Naval Man-of-War.

"I wish to acknowledge J. C. Ward's contribution to the Ships History, for the publication of the "Log of the U. S. S. EDISON" February 1946 in Charleston, S.C., from which I used the itinerary of the ship in the Pacific to its final destination in Charleston, S.C."

/s/ Russ Rossell August 17, 2011

Russ Rossell has now given us what we needed to complete the narrative of the active life of the USS Edison, DD-439.

The Fourth Edition of "Joining the War at Sea 1939-1945" takes up right from this decommissioning paragraph just related to us by Russ Rossell. We learn in the book the final disposition of the ship. We learn what her former Executive Officer, Captain Stanley Craw USN, said, upon visiting the decommissioned Edison in the Reserve Fleet at Charleston SC, before she went to the shipbreakers. Captain Craw made a solemn visit in a haunting anchorage, to the Edison. "None of the people who were supposed to be there were there." he tells us on page 363 of the 4th Edition of the book. That was the phrase that led me to write the book.

Next in the book, I offer my own poem, This can be found on page 378 of the 4th Edition (ISBN 0966625153 January 2009). These lines appear, along with an unforgettable photo, that I, the author, snapped with a Kodak 35 camera. Here is that poem:

What do old warships say,

when they've come 'longside their final quay?

"My plates are sore, but my spirit's good,

Isn't that where his seabag stood?

Move a bit friend. I need see the sea.

Sorry! You're still. You're just like me.

I see shapes, but hear no sound.

Whisper to me. Are we fast bound?"

Home | Joining The War At Sea | Triumph of Instrument Flight