The new Fourth Edition with 44-page Index

Joining the War at Sea 1939-1945

- Draftees or Volunteers

- U.S. Military Draft and Pearl Harbor

- Warship Building

- World War 2 U-Boat

- Collision at Sea

- Operation Torch

- Sea-based SG Radar

- Attack Transports Sink

- Assault Landing

- Tiger Tank

- Darby Rangers Setback

- Eisenhower Needed Seaports

- Rohna Sinks; 1000 Soldiers Perish

- Death, Survival, and Leyte Gulf

- Annunciator Speaks!

- World War II Sinking

- British Rescue Ship Toward Sunk

- Self Inflicted Wounds

- No Abandon Ship for USS Ingraham

- Rohna Tragedy Tops Transport, Destroyer Toll

- Four Chaplains

- U-73 speaks from the depths

- 300 warships/transports in "Joining the War at Sea" listed alphabetically

Troop Convoy AT-20: USS Ingraham, DD-444 sinks. USS Buck DD-420, oiler Chemung damaged, troopship SS Awatea disappears.

Navy Logs, USS Chemung Court of Inquiry fill Record Gaps; stories received in 2011 tell of survior's life challenges

Copyright 2012 Franklyn E. Dailey Jr.

Part I Background:. Convoy AT-20, a fast (15-knot) convoy with a heavy troop load and priority supplies, left Halifax, Nova Scotia for Greenock, Scotland during the 04-08 watch on August 22, 1942. In a five-minute period in heavy fog on the 20-24 watch that same day, two modern U.S. destroyers were rammed. One (the USS Buck DD-420) had her stern almost sliced off and eventually lost both propellers. Her after steering engine compartment personnel became casualties. The other destroyer (USS Ingraham DD-444) blew up and sank. Only 11 survivors were recovered. Transport SS Awatea with 5000 Canadian troopers bound for England disappeared but later turned up back in Halifax. A U.S. Navy tanker (USS Chemung AO30) was left on fire in her forward bos'n stores hold. No enemy action was involved. What occurred during this event was first recounted in my book, "Joining The War At Sea 1939-1945." I was a just-graduated Navy Ensign and Convoy AT-20 was my first experience at sea in World War II. My book was published in late 1998 and has now seen several edtions. More details on this tragedy have since been adduced from ship logs and from the report of the Court of Inquiry examining the collision role played by the Navy tanker, USS Chemung. Book buyers are invited to download this page as some of this narrative has exapanded beyond the scope of the book.

(Note: For those not accustomed to naval time, 0400 is 4 a.m. in the morning, 1200 is noon, 2000 is 8 p.m. and 2400 is 12 p.m or midnight. Watch officers shortened their initial time entry for each watch period by leaving off two zeroes.)

The battleship USS New York and the light cruiser USS Philadelphia provided the Ocean Escort for Convoy AT-20. Embarked in Philadelphia was CTF 37, Rear Admiral Lyal Davidson, commanding the entire operation. Captain John Heffernan USN, as ComDesRon 13, led a destroyer screen consisting of a full destroyer squadron of nine of the newest U.S. destroyers. Heffernan had his flag on the USS Buck, DD420. USS Woolsey DD437, USS Ludlow DD438, USS Edison DD439, USS Wilkes DD441, USS Nicholson DD442, USS Swanson DD443, USS Ingraham DD444 and USS Bristol DD453 completed the ASW screen. Buck was a one stacker of the Sims class. The rest were Benson-Livermore two stackers with elevated foc'sle decks. Davidson's Task Force had been assembled to make sure that neither Germany's subs nor its surface forces could interfere with AT-20's passage. Chapter Four of the published book addressed the events of the night of August 22, 1942. An important addition to this Appendix is the cruising disposition of Convoy AT-20 on the night of August 22, 1942. It is Exhibit 6 of the Court of Inquiry Record and was furnished to me by Robert McBrayer. In the 12-ship convoy with New York and Philadelphia were just ten other ships. These ships bore vital resources. Heavy in troop transports, AT-20 was conveying approximately 50,000 soldiers to the British Isles. Its tanker conveyed vital oil and aviation gasoline and its supply ships bore essential components for infrastructure in a massive manpower buildup for Britain. Few convoys merited a battleship and cruiser. Earlier convoys would have been wonderstruck at a screen escort of nine new destroyers.

Part II-Official Navy Records on Convoy AT-20: In 1985, I visited the National Archives on Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington DC to re-acquaint myself with the logs of the USS Edison, DD439, on which I served from July 1942 to October 1944. Many of Edison's logs were written in my hand. My notes taken during that visit furnished the basis for some of the events covered in my story. That story is now available in book form. In its summary of the sinking of the USS Ingraham, DD444, a screening destroyer assigned to Convoy AT-20, one naval website mis-identified the ship that struck her. Understandable! Fog was the first enemy encountered after the convoy's departure from Halifax. Fog hides facts. Then, I received e-mail feedback from the book Some e-mails addressed the very same matter in which that one website erred, specifically, in mis-identifying the ship that struck the Ingraham causing her to explode and sink. As a result, I went into greater detail on the website www.daileyint.com, in an Appendix D (see "Self Inflicted Wounds" in the left column) to the original draft version on the web. Up to this point, there was substantial agreement as to what had occurred in terms of damage and losses on that fateful night but there was little public information as to why two collisions occurred in this powerful convoy. I was drawn back into this tragic episode and felt that further insight might come from examining a number of ship's logs for the 2000-2400 watch of August 22, 1942, and for as many subsequent watch periods as seemed fruitful.

In company with David Shonerd, Captain USN (Ret), my Naval Academy roommate for our Plebe Year (1939-40), on the 13th of November 2000, he as my driver, guide and overnight host, I visited the new National Archives in College Park, Maryland. David had telephoned the Archives that morning. The ship's logs that we needed had been pulled from the stacks and were ready for examination. I consulted the logs of the USS Philadelphia CL41, the USS Buck DD420, the USS Bristol DD453 and the USS Chemung AO30. This examination provided important details on the two collisions that occurred in Convoy AT-20 during its first night out of Halifax.

It did not take long to find what we were looking for, watch log information identifying specific vessels in specific incidents. In the paragraphs with quote marks that follow, I have transcribed ship's logs for selected watch periods. I might note here that David and I were not typical of the many doing research that day in November 2000. We were both about to be 80 years old. One of us had participated in the World War II event that we were examining. The other was a warship and wartime qualified watch officer who served in the Pacific during most of World War II. Rapid focus on the key paragraphs of the 1942 logs was achieved. I am indebted to Dave Shonerd not only for the physical transport and Archives arrangements but also for helping to pinpoint so quickly the essential log entries related to the loss of the USS Ingraham and the damage to the USS Buck.

(An important additon to official Navy Records of Convoy AT-20): Those who read these lines need to know that on March 5, 2001, I, Franklyn E. Dailey Jr., received from Robert McBrayer, a U.S. Postal Service Priority Mail pack containing excerpts from the copy of the report of the Chemung's Court of Inquiry, which met first on August 28, 1942, to examine the causes for the loss and damage incurred in Convoy AT-20. The next paragraph is substantially more complete based on those Court of Inquiry excerpts, one important element of which was the complete cruising disposition of the entire convoy and ASW screen. In my original write-up, I had the convoy in three columns when actually four columns existed, though Column 1 still remains the troubled column. Captain Robert McBrayer USNR (Ret) served on the USS Chemung from 7/55 to 7/57. Chemung was in service in the Pacific during this period. McBrayer's experiences include many rough weather refuelings including one when the oil hose parted while pumping to a carrier. He recalls, "The Chemung was hit several times by carriers while refueling them. The Bonhomme Richard was particularly a problem. She hit us almost every time she came alongside. Our gun tubs showed it. We took to putting heavy fenders over each time." Captain McBrayer is involved with the Chemung reunion group, helping with their newsletter and their get togethers. He reports that Chemung plankowner George Bird, one of the witnesses before the Court of Inquiry convened on August 28, 1942, is still active in the group, with wife Karen Bird also taking an active part. There are 274 on Chemung's mailing list and Captain McBrayer states that interest in Chemung's WW II record remains high.)

For a better understanding of transcribed mateial, let me lay out how Convoy AT-20 would have appeared on August 22, 1942 to an aircraft flying overhead. For the convoy cruising disposition, and other details in this Appendix, I am indebted as noted above to Robert McBrayer and excerpts he forwarded to me from the Court of Inquiry Record. His copy of the Court of Inquiry Record had been made available by George and Karen Bird. George was serving on the Chemung in Convoy AT-20 and was injured in the collision which occurred when the Ingraham steamed into the path of Column 1 of the convoy. (On January 22, 2011, the website author was able to add the story of Seaman 2/c Robert Francis McLaughlin USN , on watch in the Chemung's radio shack, who received major injuries in the collision. This story is added to the Chemung story below as Part III-Survivors Stories from USS Chemung received in 2011.)

Steaming on base courses a bit south of east at 14.5 knots, AT-20 was formed in four ship columns. Column 1 would be on the port or north flank of the eastbound convoy, Column 2 would be next to the right (south), Column 3 next right and Column 4 on the starboard or south flank. (the number of a ship in the convoy will be preceded by #) The lead ship in Column 1 was the cruiser, USS Philadelphia aka #11, the lead ship in Column 2 was the SS Letitia aka #21, the lead ship in Column 3 was the USS New York aka #31, the convoy guide, and the lead ship in Column 4 was U.S.A.T. Siboney aka #41. The columns were to maintain spacing between columns of 1000 yards. Each column contained three ships. The distance to be maintained between ships in column was 600 yards. Behind Philadelphia in Column 1 came the SS Awatea #12 with the Navy oiler USS Chemung #13 next astern. Behind Letitia in Column 2 was SS Strathmore #22 followed by SS Duchess of Bedford #23. Behind New York in Column 3 came MV Winchester Castle #32 followed by SS Ormonde #33. Behind Siboney in Column 4 came SS Reina del Pacifico #42, then a 'reefer' (a refrigerator ship, AF-11) Polaris #43 in that order. Carrying the Screen Commander, the destroyer USS Buck aka #2 had an assigned screen station in an arc from dead ahead of the convoy to about relative 320 degrees from the convoy base course. USS Ingraham aka #4 was next on the port side to about 270 degrees relative to the lead flank of the convoy ships. USS Bristol, #6, had the port quarter. Matching Buck's position on the port bow, was USS Ludlow on the starboard bow as #3, next behind her was USS Woolsey #5 and on the starboard quarter was my ship, USS Edison #7. This screen patrolled from 4000 to 6000 yards from the nearest convoy ships. The remaining destroyers were ahead 7 miles with USS Wilkes #15 patrolling dead ahead on either side of the base course, USS Swanson #16 broad on the port bow of the convoy and USS Nicholson #17 broad on the starboard bow. It is understandable that the Buck and Philly would wish to maintain best visual contact for use of visual signals, especially flag hoists and blinker. Convoy ceased zigzagging at 1938 in preparation for night steaming, sunset was at 1955 and at 2035 the fog towing spars were ordered streamed for all convoy ships by flag hoist. Buck's report of an unidentifed ship on her port side steaming south sent the convoy into a ship's turn 45 degrees to starboard. When that ship identified herself as USCG Menemsha, and had passed the convoy close to port, a second emergency ship's turn of 45 degrees back to the base course of 110 degrees true was executed. Admiral Davidson noted in the Court of Inquiry Record that ship #21, Letitia, not only failed to execute the two emergency turns three minutes apart but appeared to be on a base course which brought her closer to Philadelphia and away from New York. The failure of Letitia to respond to proper course instructions given by flag hoist prompted Admiral Davidson to send the Buck on its mission to correct Letitia's actions. This put in motion the chain of events, which in an under-evaluated fog condition, led to the disasters of the evening.

During the 20-24 watch on August 22, 1942, Convoy AT-20 sailed into fog conditions which were shallow vertically, but horizontally were tantalizingly, dense and light, moment to moment! Fog became the master of the evening. The Philadelphia's 16-20 log notes that she streamed her towed spar astern (referred to in the Court of Inquiry Record as a "fog buoy.") with 400 yards of line. This was a fog-induced measure to provide the next ship in line a visual object on which to keep station. Let me introduce a personal observation about the fog of that evening. From Edison's position abaft the right beam of the convoy, no other ships were visible. Understandable, as we were 5000 yards out from the convoy. We encountered a wreathy swirling treacherous fog right down on the water. We could occasionally see the moon up above so vertical visibility was better than horizontal visibility. I now have an Navy pilot's experience in fog and I believe that all persons interrogated by the Court of Inquiry answered the visibility estimate question with honest but flawed responses. Most erred in reporting visibility at one or two or three thousand yards. One witness stated "one quarter to three quarters of a mile." Instead of the inference of uncertainty in distance from such a report, if it had been understood as "now one quarter and then moments later three quarters" the report would have been more realistic. But the interrogator never pressed the witness on how he arrived at his estimate and what he meant by it. On Edison's bridge, we used a handheld device whose tradename I believe was a Statimeter, to deduce an estimate of distance to nearby ships. One had to enter the other ship's masthead height into the device, bracket that masthead in the arms of the device by capturing it from its top to the waterline, and read out the distance to that ship on another point of the device. That night a masthead might have been seen but the waterline below it obscured. No Inquiry witness mentioned use of anything but seaman's eye in the estimates they gave. In fog, keeping station on a towing spar ahead, there would be a tendency to "inch up" to give the helmsman and OOD the best look at the spar. In column to column spacing the tendency would be to close in a bit to keep the next ship over in sight. I believe that some of the witnesses certainly did see some ships at greater distances when the fog in that direction would momentarily break, but they might easily miss a ship close aboard wreathed in fog. Only the Philadelphia bridge or flag bridge personnel might have had better visibility estimates because the Inquiry Record has a number of references to a "radar plot" on Philadelphia. We (on a destroyer) had no such plot. Nor did the other ships present. In Column 1, for activities behind the Philadelphia, conning officers and OODs had no time to react due to these conditions yet the two destroyers sent on convoy intervention missions into Column 1 of AT-20 acted as though they fully believed their own estimates of visibility. Case in point: The USS Buck attempted to penetrate Column 1 in a crossing situation and testimony reveals that she momentarily slowed her engines to avoid hitting Philadelphia's towing spar. That spar would have been 400 yards behind Philly and the next ship in line was to keep station 600 yards behind Philly. I am sure that Buck knew this, but, because of a false sense of security about visibility, and not seeing Awatea, assumed Awatea was in fact not 200 yards behind that spar but even further back. The Inquiry Record shows that Buck almost made it. Awatea sliced into Buck's starboard side behind Gun 4 almost at right angles as Buck attempted to accelerate past Philly's towing spar on her port side. The Inquiry Court noted that had Awatea turned to port (toward Buck's stern, as the General Prudential Rule would advise), Buck might have made it across Awatea's path. We are dealing with seconds now in this re-creation and making assumptions that Awatea's conning officer had a full appreciation for Buck's prior movements which he did not have! When Ingraham came into Column 1, on a mission to offer aid to the Buck/Awatea collision event, although the ship to ship final aspects to each other were quite different from the Buck/Awatea event, the misjudgments due to erratic estimates of visibility led to sudden sightings at distances so close that only emergency mitigation maneuvers could be attempted. These desperate final and unsuccessful efforts to avoid collision had their origins in the same fog problems that Buck and Awatea just minutes earlier had failed to resolve. And again in the final minute or two, if either ship had a prior plot of the movements of the other before sighting , there was a chance that the collision might have been avoided. Chemung had moved slightly to port out of her lane to port to avoid the Buck/Awatea collision. Ingraham was hit abaft midships by Chemung at an acute angle with the ships passing port to port on opposite courses. The consequences proved disastrous. One officer, Ensign Melvin Brown USN, my Naval Academy classmate, who was in the Mark 37 Director, and 10 enlisted ratings, survived the collision, and subsequent explosion of Ingraham's armed depth charges as she sank.

The aspect that I wished the Inquiry interrogator had pressed a little harder was Ingraham's speed in her convoy entry maneuver, and whether it related to any TBS orders from CTF 37. I relieved Ensign R. F. Hofer USN on Edison as JOOD underway at midnight and he told me in our 2330-2400 discussion that Ingraham has been directed to "close the convoy at high speed." A member of the destroyer Swanson (DD-443) bridge crew has stated on a web page that the TF Commander, using the TBS, advised the Ingraham to use caution in approaching a ship column in the convory. The lowest estimate given in the Inquiry Record of Ingraham's speed entering that convoy was 20 knots and many gave estimates of 25 knots. I believe that is too high. Ships approaching on opposite or near opposite courses leave an impression of higher speeds due to the relative motions. The Inquiry Record of Admiral Davidson's TBS orders, and the same orders as understood by the Ingraham watch officer on the bridge, leave us with the Ingraham's actual speed about as wreathy as that fog.

From the log of the USS Philadelphia, CL41

Log approved by Paul S. Hendren, Commanding Officer; date is August 22, 1942.

"20-24 Steaming as before. 2002 USS Edison cast off. 2015 Changed course to 115 deg. (T) Changed speed to 13.5 knots. 2020 Changed course to 110 deg. (T), changed speed to 15.5 knots. 2030 Changed speed to 14.6 knots. Strange ship entered formation, bearing 270 deg. Relative, distant 1000 yards, passed well clear. 2055 Streamed towing spar, 400 yards line. 2100 Ship sighted at 2005 identified as USCG Menemcoe. (Log should have identified her as the Coast Guard manned USS Menemsha, according to Pieter Graf of The Netherlands, who did extensive research in 2008 to enable this correction.) 2230 Destroyer assumed to be #2 (USS Buck) sighted passing astern from port quarter. 2233 Collision astern, presumed to be between #2 (USS Buck) and #12 (SS Awatea). 2235 Destroyer sighted bearing 250 deg. Relative, on opposite course. 2238 Violent explosion on port quarter. 2238 General Quarters, all hands in life jackets. 2238 Emergency turn to starboard to course 155 Deg. (T) 2250 Changed course to 110 deg. (T) 2310 Radar contact bearing 034 deg. Relative. 2334 Secured from General Quarters, set Condition of readiness " II Mike"; set material condition "Baker Plus."

H Lockwood, Lt (jg) USNR.

My explanatory notes:

(1) The "emergency turn" noted above was 45 degrees starboard. U.S. convoys used the British Mersigs signal book when steaming with mixed nationality convoys and escorts. The 45-degree emergency turn to starboard was signaled at night with flares and was executed immediately. It was a "ship's turn" with all ships turning at once.

(2) There have been some questions raised in earlier queries concerning the time of the events on the 20-24 watch on August 22, 1942. I discovered in Philadelphia's next watch period entry, the 00-04 mid-watch, that her clocks were set ahead one hour to Zone +2 time on that ship. All ships were not necessarily keeping the same local time and even when they were, clocks used as reference by log writing officers varied.

(3) The watch stander on the Philadelphia was recording Philadephia's actions and observations on his watch. CTF 37, aboard Philadelphia, gave the USS Buck an order over the TBS to "drop back" to enter the convoy. Buck's log shows that her mission on that fateful evening was to give the Letitia, leading Column 2 in the convoy, a message about where CTF 37 wanted her to keep station. Very likely a bull horn (loud voice) or a gun to shoot across a written message would be used to pass the information. Radio silence was being observed to deny German U-boats low frequency radio signals that the latter might intercept to locate convoys. The Navy vessels had TBS transmitters for voice communication with each other on higher radio carrier frequencies around 70 megacycles. These shorter radio waves were assumed to be line of sight and would not give location away. (Lack of discipline in the form of unnecessary chit chat in some convoys revealed that TBS transmissions could actually carry beyond the horizon.) The merchant ships did not have TBS equipment and relied on low frequency radio, which would bounce through the atmosphere in sky waves and in ground waves. The USS Chemung had TBY, a battery powered version of the TBS. So, to maintain radio silence, messages to and from merchant ships relied on MERSIGS visual flag signals in good visibility and flares for emergency turns at night. In fog, the only option for a vital message, if radio silence was to be maintained was to have a messenger ship go alongside, as the Buck was assigned to do, for passing information to the SS Letitia. (Why the Buck did not drop back astern of convoy and come forward between columns to accomplish her message mission, but rather chose to double back down the port side of the convoy and attempt to enter the convoy behind Philadelphia and then pull up alongside Letitia was questioned without resolve in Court of Inquiry excerpts available to me on March 15, 2001. It is possible the Buck had a break in the fog that closed in just as she attempted her maneuver.) The papers I do have from the Inquiry Record do clarify a point on what CTF 37 wanted Letitia to do. Apparently Letitia was not holding her assigned position as ship 21 in the convoy directly between 11, the Philadelphia and 31, the New York. RAdm Davidson wanted to clarify to Letitia what her assigned position was and to tell her to go there.

(4) Except for rare breaks, fog obscured the transit path of AT-20. The Philly had launched a towing spar with 400 yards of line behind her.. She saw ships only at close range and even then only in "patches" where the fog would have lifted. The Philly watch stander noted the second destroyer, five minutes later on "opposite course," proceeding, as the Buck had, down Philly's port side similar to the route the Buck had taken just before her. The Buck had been noted crossing astern after which a first collision occurred. The second destroyer barely made it down the port side, and was not noted in the Philly log entry as having crossed astern. Philly's last visual sighting of this second destroyer, noted to be on an opposite course, was followed by a "violent explosion." Fog did not obscure the flash of that explosion but did obscure the ships involved. That violent explosion was the Ingraham DD444, and though the writer of the log on the Philly ventured no collision explanation to go along with the explosion, we know from other records that it was the oiler, USS Chemung, that hit that second destroyer, the USS Ingraham. Following this collision, Ingraham exploded. These collisions were no fault of the ships in convoy. Those ships did not even have the knowledge that destroyers would be moving about in the paths of the convoy ships. For their part, the destroyers involved had orders to "deliver a message" (Buck) or to investigate a collision in the convoy (Ingraham), but could see little. The destroyers involved could not even be sure that the towing spars being used in the fog would keep ships in the convoy perfectly lined up. Current or wind could cause the second ship in column to be offset from the line of the one ahead and such an offset would become greater the further back a ship was.

From the log of the USS Buck DD420

L.R. Miller, Lieut. Comdr. USN Commanding, approved this entry.

"20 to 24

Steaming as before. 2005 formation base course changed to 110 deg., true, 135 deg. PSC 2025 Sighted strange ship on starboard bow, this ship proceeded to investigate. Convoy executed emergency turn to starboard. Ship identified as friendly, USCGS Menemcoe. (Note: The Indian name of this Coast Guard ship sounded different to the watch stander on the Philly.) This ship proceeded to overtake convoy at 20 kts 190 RPM. (Note: "this ship" is the Buck, not the stranger.) 2150 Passed close by Column 3 of convoy, leaving USS New York to starboard. 2210 Prior to reaching screening station, while still only 3000 yards ahead of convoy, this ship was ordered by CTF37 to deliver a message to the SS Letitia, stationed in main body. This ship reversed course to port, steaming at 10 kts, 90 RPM. Contact maintained with main body by radar. (Note: No ships had short wave radar such as SG. The best any U.S. destroyer in this convoy had was air search radar, the SC. It was worse than useless for penetrating the main body of a convoy in fog.)This ship on opposite and parallel course to convoy, sighted USS Philadelphia. Captain at the conn: This ship turned to port in order to pass astern of the Philadelphia, after which proposed plan was to parallel the convoy and deliver message to Letitia from between columns 1. and 2. 2222 Maneuvering on various courses and various speeds as necessary to pass close astern of Philadelphia 2225 This ship was rammed on starboard side of fantail just aft of gun #5 by the bow of the SS Awatea. Ship just astern of Philadelphia. Collision took place at 90 degree angle, the bow of the SS Awatea piercing two thirds of the way through this ship at point of collision; this ship showing turns for 20 kts, 190 RPM 2226 Explosions felt below stern of this ship as a depth charge which had shaken loose exploded. (Note: A lanyard was attached to the safety fork and to a fixed portion of the mount so that when the charge rolled off into the water, the safety fork was withdrawn and the charge exploded a few seconds after rolling off into the water. This was a violation of safety orders. The Court of Inquiry Record also reveals that the #4 and $5 projectors on Ingraham racks had their depth charge safety forks removed at dusk and were therefore "live" if they rolled off or were knocked off that ship. Again, a violation of instructions.) 2229 All engines stop. Stern of this ship clear of transport. Fantail reported damaged such that any use of engines might prove fatal to stern of ship and men trapped there. (Note: Men were in after crew's compartment.) Reported that port shaft was intact and that port engine might still be used. Damage control party investigating damages and commencing rescue work. Wounded men taken to ward room as soon as extracted; ship's doctor in charge of caring for wounded personnel. After compartments reported flooded. Watertight integrity reported to have been investigated and found to be satisfactory. Ship adrift and darkened top side as rescue work proceeding on stern."

This log was signed by C.R. Barton Lieut. (jg) D-V (G) USNR

Barton added a correction:

"Correction: this speed being made just prior to collision. When collision was seen to be unavoidable, all engines were stopped; upon stern becoming free of transport, the port engine was given 1/3 ahead, then standard, and responded to take stern somewhat clear of depth charge explosion."

USS Buck log continued:

"00-04 condition Affirm set; rescue and repair work in progress. 0211 USS Edison arrived at scene; standing by 0235 Rescue work in damaged compartments completed; following named men missing, Rowse, Louis Glennwood, 372-23-21, SC 3/c, USN; Dungan, Raymond Lee, 272-43-99, Sea 1/c, USN; Evans, Roy, 311-36-50, Sea 2/c, USN; Davis, Arthur Edward, 283-64-91, Sea 2/c USNR; Duro, Howard Arthur, 646-18-49, Sea 2/c, USNR; Nemeth, Wendell 633-88-33, A.S., USNR. 0310 Commenced maneuvering various speeds on port engine using varying amounts of rudder to bring the ship to heading 310 deg.t. 0345 Commenced lying to; port engine racing, propeller believed lost; no way on ship. Set condition of readiness two mike on gun and torpedo. On batteries.

Robert K. Irwin, Lieutenant, US Navy"

"04-08

Lying to as before. 0427 secured main engines 0530 sighted USS Chemung; standing by to receive tow line from her .0630 USS Chemung maneuvering alongside; starboard motor whaleboat lowered to transfer medical supplies to that ship and assist in passing tow line. 0740 starboard motor whaleboat hoisted and secured. 0750 Tow line from Chemung, consisting of 600 feet of mooring wire in place, that ship commencing to steam ahead slowly."

G.H. Harrington

Lieut. USNR

"08 to 12

Underway as before 0924 tow line parted, lying to waiting to receive another line 1100 tow line secured consisting of 120 fathoms of 10 inch manila and 15 fathoms of anchor chain 1135 tow line parted, lying to, waiting to receive another line."

C.M. Crouch

Lieut. (jg) D-V (t) USNR

From the log of the USS Bristol DD453: Approving these entries,

C.O. LCDR Chester Clark Wood USN

Nav. LCDR Morton Sunderland USN

Bristol's log shows that she passed through the boom at Halifax NS on the 04-08 watch on August 22, 1942 and proceeded to join the screen of Convoy AT-20 which was in the process of forming up for transit to Greenock, Scotland. Transcription from this log begins for the evening watches of August 22, 1942.

"18-20 Steaming as before 1850 Swanson (Note: USS Swanson DD443) laying depth charges. This ship (Note: meaning Bristol) drawing ahead in screen. (Note: Likely covering part of Swanson's sector.) 1940 Screening vessels returning to normal stations 1940 Sunset. Darken ship"

W.J. Lederer ,Lieut. USN

"20-24

Steaming as before. 2040 USS Ingraham reported to be resuming station. USS Bristol moved to regular station on port quarter of convoy. 2142 USS Swanson passed about 2000 yards on our port beam resuming station. 2225 Observed explosion on starboard beam, distance about 4000 yards 2226 On orders from SOPA (Note: Senior Officer Present Afloat, CTF 37) USS Bristol stood over to investigate. Picked up two officers and nine enlisted men from USS Ingraham which ship had just sunk."

Wm J. Flather III

Lt. (jg) USNR

Aug. 23, 1942

"00-04 Standing by USS Chemung and continuing search of area for other possible survivors. List of survivors from USS Ingraham picked up: Owen, Roy, Ens USNR; Brown, Melvin Ens USNR (Note; Mel Brown was a June 19, 1942 graduate of the US Naval Academy and classmate of the author. He was commissioned an Ensign USN); Scaffe, Charles PCBM USN 261-69-57; Cooper, Priest G. Jr. Cox. USN 311-26-71; Anderson, Ray M. Cox. USN 371-59-76; Woody, Coleman E. S 2/c USN 355-69-50; Wilhelm, Luther Leonard S 1/c 266-39-37; Allen, Frank Edward, F 1/c USN, # unknown; Corcoran, Thomas Phillips S 2/c USNR # 642-03-40; Kennedy, Leon L., F 1/c USN #256-36-75; Cooper, Ernest Charles S 2/c USNR #614-06-92.

0215 Joined USS Buck DD420, badly damaged by collision. Circling Buck and Chemung as protective screen. Boilers #1 & 4 in use. Ship darkened, condition of readiness three, material conditions "Baker." Medical care being given to men rescued."

T.Fraley Jr

Lt. USNR

"04-08 Steaming as before. Screening USS Buck and USS Chemung. Screened ships lying to, this ship circling at 12 knots. USS Chemung passing tow line to USS Buck. All survivors under medical care."

W. J. Lederer

Lieut. USN

"8-12 Steaming as before. USS Chemung has USS Buck in tow on course 310 deg. T. 0928 Tow line parted. Began steaming in circle screening both ships. 1015 USS Buck again in tow. Began patrolling at 12 knots area 45 deg either side of tow of USS Chemung distance about 400 yards. Base course 270 deg. T."

Wm J Flather III

Lt (jg) USNR

"12-16 Steaming as before. Patrolling station ahead of Chemung and Buck in semicircle of 4000 yard radius beam to beam. 1427 Heavy rain squall with reduced visibility 1500 Squall passed over. Chemung estimated to be on course 260 deg. PGC speed 5 knots."

T. Fraley Jr.

Lt. USNR

From the log of the USS Chemung AO-30:

Log page approved by J.J. Twomey

"20-24 Steaming as before. 2235 Collision with destroyer.

Major injuries. Commander John J. Twomey USN; Ensign Neal McEwen Craig Jr. USNR; Holland, John - Service number unknown RM 3/c USN; McLaughlin, Robert F. #642-05-58 S 2/c USNR; Minor injuries: Lieut. Ray E. Wingler USNR; Dehm, Francis A. 403-57-29 S 2/c USNR; Hymmel, Walter M. 328-49-10 FC 1/c USN; Sokolowski, John A. 311-93-79 S 2/c USNR; White, Ralph Iron Jr. 614-09-17, S 2/c USNR."

W. Barnett

Explanatory Notes

The log entry immediately above is the total mention in Chemung's logs of a collision that left Chemung on fire forward, with flames visible for miles as the fog cleared. I surmise that Commanding Officer Twomey's major injuries may have incapacitated him, possibly requiring his Executive Officer to take over. Such a change of command could have influenced the pace of Chemung's immediate damage actions and also kept the CO from supervising some of the later record keeping. In the story "Joining The War At Sea 1939-1945", I recount how the Chemung asked Edison to come alongside and put Chemung's fire out. Had their CO not been injured, I doubt that Chemung would have asked a destroyer to put her fire out when her own equipment and training were so much more extensive. With understandable delay due to their skipper's injuries, Chemung's crew did then deal effectively with the damage and with the subsequent fire.)

Another interesting event which preceded the events above by not more than half an hour was recorded in Admiral Davidson's testimony to the Court of Inquiry. He directed the Edison in the inner screen on the starboard flank of the convoy to come alongside the Philadelphia, take aboard meningitis serum, and deliver it to to the U.S. Army Transport Siboney, convoy ship #41. The fog had not yet intervened and that transfer proceeded without incident. That transfer also occurred without the knowledge of Ensign Dailey who was completely unaware of it until he read the Inquiry Record sent him by Robert McBrayer on March 5, 2001.

Epilogue: Ingraham was lost while escorting Convoy AT-20. Within 15 months, torpedoes coursing through the Mediterranean Sea had sunk the USS Buck, the USS Bristol and the SS Awatea. Only my ship, and the Chemung, of this mini-convoy back to Halifax, on August 23, 1942, managed to survive World War II. The other damaged ship from AT-20, SS Awatea was lost at sea off Tunisia. So, in the episode of AT-20 that began on August 22, 1942, shared by the SS Awatea, the USS Buck DD-420, the USS Ingraham DD-444, the USS Edison DD-439, and the USS Chemung AO-30, only the last two named, survived the war.

Part III-Survivor Stories from USS Chemung AO-30 received in 2011.

Here is the first, received 01/17/2011, reproduced verbatim:

"Dear Sir,

I have wondered for many years what happened to my father's legs in the North Atlantic. You have answered my questions.

My father was born in 1922, Robert Francis McLaughlin. In August of 1942 (the 22nd to be exact), he lost his legs in a ship collision in naval convoy in the North Atlantic. He was a radioman on the Chemung. I thought he was 19 when it occurred but I find he was just 20 when the accident occurred. I thought it was a great battle with a German ship that took his legs. He wouldn't talk about it. I was 14 when he died and we never had any of the deeper discussions that might have occurred if he had been with us longer. The only thing I remember him saying is that the other ship sunk. It makes sense to me now.

Thank-you for answering many of my questions. I am looking to buy your book and get more information about that fateful day.

Anne Marie (McLaughlin) Harris"

The e-mail above leads, directly, to a remarkable discovery. As the expression goes, we can "put two and two together," after 69 years! In the compilation of the injury summary contained in the 08/22/1942 log of the USS Chemung, we find (above, see Chemung log excerpt) one of the names after "major injuries," "McLaughlin, Robert F. #642-05-58 S 2/c USNR." It was forwarded to me and included in Captain Robert McBrayer USNR's material forwarded to me after he, McBrayer commanded the USS Chemung, from 1955-57. He had the benefit of the ship's history of the USS Chemung, including passages from her log on the night of August 22, 1942. This log was approved by Commander Twomey, Chemung's Commanding Officer, himself among the "major injuries" noted. This will come as discovery by Anne Marie Harris, who received from her father, and that reluctantly, only that he was on duty in the Chemung's radio shack when the collision occurred. I have learned from Anne Marie that her Dad mentioned "a barrel rolling around." He had left the radio shack to find out what had occurred, and while out on deck encountered a 'barrel' that had come loose, and that barrel injured one leg above the knee , the other below the knee, resulting in amputation, prostheses, and crutches for the rest of his life. (Entered 01/23/2011, based on input from Robert McBrayer, George and Sue Bird, and Anne Marie Harris.)

Robert Francis McLaughlin was born in 1922. He was in the Navy, serving in the 'radio gang' of the USS Chemung AO-30, when that ship collided with the destroyer, USS Ingraham DD-444, while both were in Convoy AT-20, eastbound from Halifax, NS, to Greenock Scotland, during the 20-24 watch on August 22, 1942. McLaughlin sustained major injuries in the collision, eventually losing parts of both legs, one above the knee, the other below the knee. It is not known when he was actually discharged from the Navy but rehab at Walter Reed Hospital in Washington DC very likely took place, since he married, and then raised a family of three children while living in a Maryland suburb adjacent to the District of Columbia. One of those children is now Anne Marie Mclaughlin Harris, an ER nurse, who has a brother, Robert Francis Harris, whose twin sister has passed. It is known that her father, despite his injury, with prostheses and crutches, held a responsible position with the U.S. Navy's civilian personnel division located in the Pentagon. He passed in 1966 and is buried at Arlington. (Entered 01/28/2011, based on information from Anne Marie Harris.)

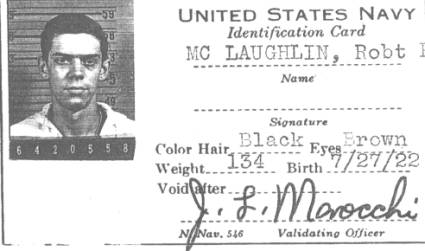

Navy ID for Robert F. McLaughlin issued just days before USS Chemung AO-30 sustained a major collision in Convoy AT-20 (received under postmark 08/12/2011, entered here 09/24/2011)

Anne Marie Harris' husband, Richard A. Harris, served in the U.S. Air Force during the Viet Nam conflict. The couple have four children, Laura Jean and Robert, twins, age 40, Sean Michael 38 and Heather Michelle 36. Anne Marie's father, Robert Francis McLaughlin married Mary Elizabeth Goodwin in Hartford Ct. in 1949. (01/30/2011, based on information from Anne Marie Harris.)

More discovery is contained in an e-mail dtd 09/19/2011 rec'd 09/20/2011 from Brian Rice:

"Sorry Frank it took so long to get this together. My dad Thomas W. Rice was in the Navy during WW2. One of the ships he was on was the USS Chemung. He was a gunner's mate. He was born in Fargo N.D. April 24, 1923. He passed away Oct 15, 2009.

My father didn't talk about the war much. I talked with him a few times when I was a kid. He told me about a collision in the Atlantic where the Chemung collided with a destroyer or cruiser on a foggy night and sank. I think it took the rear end off. The ship was on fire and he aided a medical Dr. with the amputation of a crew member's leg or legs and he dumped them overboard.

I have some pictures and I will forward them to you. Brian Rice" (He forwarded the three below/Author)

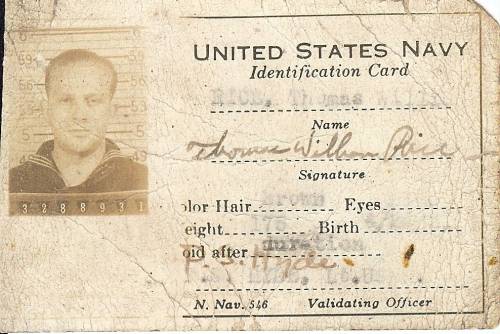

Navy ID and photo if Gunner's Mate Tom Rice

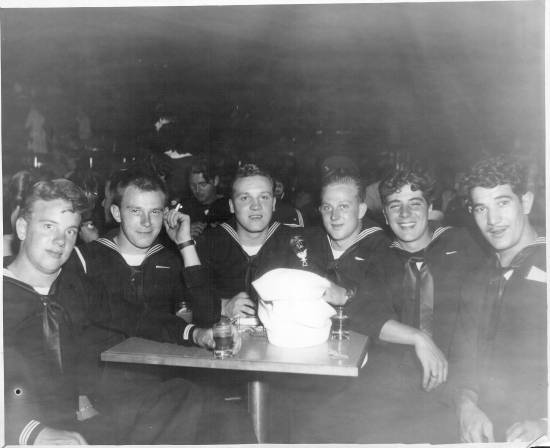

Tom Rice and shipmates from USS Chemung AO-30 in 1942; Rice is third from right

Author's Note 09/24/2011 More to follow.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The content of this web page is mainly based on feedback which resulted from the publication of "Joining the War at Sea 1939-1945." The First Edition, first printing, was published in 1998 and went through six printings. Prior to publication of that first edition, with business associate Morris Rosenthal, this website, www.daileyint.com was created about 1995. One of the first purposes for the website was to provide a place for draft editions of books to reach readers, who might then indicate satisfaction or dissatisfaction with what they were reading on the website. A second object, which proved the more enduring, was to receive feedback on the stories themselves, in amplification, and to sharpen the accuracy. The process has been quite successful as web pages like this one demonstrate. Now in its Fourth Edition, the book has benefited from improved accuracy. Website readers have benefited from extensions to the story that either were not available, or not appropriate to include in the book itself, but certainly have added to our knowledge of what happened in the Atlantic and Mediterranean in World War II.

Home | Joining The War At Sea | Triumph of Instrument Flight