The new Fourth Edition with 44-page Index

Joining the War at Sea 1939-1945

- Draftees or Volunteers

- U.S. Military Draft and Pearl Harbor

- Warship Building

- World War 2 U-Boat

- Collision at Sea

- Operation Torch

- Sea-based SG Radar

- Attack Transports Sink

- Assault Landing

- Tiger Tank

- Darby Rangers Setback

- Eisenhower Needed Seaports

- Rohna Sinks; 1000 Soldiers Perish

- Death, Survival, and Leyte Gulf

Rohna Tragedy Tops Transport, Destroyer Toll

300 warships/transports in "Joining the War at Sea" listed alphabetically

Operation Torch

French Navy Resists as Jean Bart Duels U.S. Battleship and Cruisers

This page includes a good tactical overview of the beginning of the U.S. effort to regain initiative after the low point of Pearl Harbor.

Copyright 2012 Franklyn E. Dailey Jr.

Author Franklyn E. Dailey Jr., Capt. USNR (Ret), appears in three episodes of the History Channel series, "Patton 360:" He is the author of "Joining the War at Sea 1939-1945," which provides detail on World War II invasions at Casablanca and Sicily plus Salerno , Anzio, and Southern France. (Early Feedback: A growing number of readers have signed on to this story. A person who lives near me saw an article in a local paper which contained my website URL. He looked up my name in the local telephone directory and called me relative to the chapters on the "Torch" invasion aimed at Casablanca. He did not tell me his name but did offer that he was not a participant in WW II. His call was that of a quietly indignant person who questioned whether the Jean Bart could actually have been firing on U.S. warships. He drove home this point, that the French "were our Allies in WW II", so it was inconceivable to him that the activity described in the story could actually have taken place. I attempted to re-cast those events for him but it was clear at the end of the call that I had not convinced him. FEDJr. 12/16/97)

A New Phase

I am aware that there are times in this narrative, especially when it shifts from present tense to past tense and then back again, that the reader may wish that I had stuck to one perspective or the other, "being there", or, "looking back". As a participant, I did not at the time have some of the perspective that I gained from reflections in later years. For example, the preparations for the landings in North Africa opened a new phase in the Edison's life, and mine. I had many questions then about tactics in the North Atlantic, not I must say of any coherent sense of how things might have been different, but just half-formed puzzlement. The human has the capacity to set questions aside, to submerge them slightly, and move on. Going into the next phase of Edison's seagoing operations, I had no sense then that it even deserved identification as the "next phase" in the war history of the Edison. It was all new to me, and I, like my shipmates, just raced to keep up with challenges of new responsibilities.

U.S.S. Edison's Progress

The Edison (DD-439) went into October of 1942 with no change in radar. The SC radar was our long range aircraft detection system. Its antenna, atop the mainmast, reminded one of the wire grid formed by the two frames of the grilling basket that enclosed hamburgers for grilling, with our mast replacing the handle. Scale that hamburger wire frame up about five times and you had the SC radar. We used it constantly, but I do not recall that it ever detected enemy target aircraft where that detection made a sufficient difference in Edison's war history to be noted as such. Occasionally, it confirmed what we already knew was supposed to happen with respect to our own planes.

That knowledge often came from operations plans. Positive confirmation of aircraft identity with an electronic tool like IFF, Identification, Friend or Foe, was not available. Later in the war, our aircraft were outfitted with transpondors which would respond to our ground or ship-based radar query signals, but I do not believe that SC radar systems were ever upgraded to this capability. My own impression of SC radar was that it was just one step beyond the CXAM, an experimental radar (the antenna looked like bedsprings) which was carried by one of our battleships on the 1940 USNA midshipman youngster cruise. Midshipmen of 1940 were too low on any priority list to be "cut in" on what CXAM was all about. Somehow, we knew that the X was for experimental.

Edison attempted, as did other destroyers, to make use of the Westinghouse FD, fire control radar, for detection purposes but I do not recall any success, and was left with the impression that there was little enthusiasm even for the AA efficacy of early designs of the FD radar. It could sharpen bearing and range information on prominent objects but was certainly not designed for detection purposes, and had to be constantly justified in the eyes of the Chief Fire Controlman, Jackson, for gunnery purposes in competition with optics. Edison did not fire on aircraft under "instrument" conditions. We had no way of knowing, even if we could hear them above the cloud cover, if they were friend or foe. And even with enemy aircraft, on clear nights when the FD might compete with our optical systems, firing at an enemy aircraft would immediately give our position away to them. That was a tradeoff that Edison would not make. We fired one night off Italy when an enemy aircraft silhouette was clearly revealed by moonlight. This aircraft was not only visually identifiable as an enemy aircraft, but that identification was confirmed because it was in the act of dropping torpedoes pointed where Edison was heading. (We did not hit him. Thanks again to our lookouts, we made an emergency course change, and he did not hit us.)

The sonar was constantly being improved, one small step at a time, in every yard availability period. The greatest difference here though, took place as the result of training. The British and the U.S. agreed, with emphasis on "agreed", that training in sonar and sonar tactics was vitally important. In UK ports (the British called it ASDIC) or in US ports, Edison officers and men went to sonar schools at every opportunity. Junior officers went if there was a slot available, but to its credit, the Navy demanded that its senior officers and most proficient sonar operators, be constantly improving their ability to get more out of the equipment and to use the equipment tactically to greatest advantage. By senior officers, I mean the conning officers, the CO or XO at battle stations, and the qualified senior watchstanders underway. A depth charge attack, with good information available, was best executed quickly, so the watch crew often executed the first attack, before the ship could get to battle stations.

Later, during the heat of the Mediterranean campaign, our sonarmen could find the edge of a minefield, a really fantastic bonus resulting from the honing of their skills, one that I believe saved Edison on more than one occasion. It also permitted us to penetrate a minefield and engage in close support shore bombardment.

By the end of October 1942, Edison was not advanced greatly in gunnery proficiency from when I first came aboard. Her baptism here was yet to come. But since I brought up the question of mines, let me anticipate the landings in North Africa by stating that mines advanced to co-equal status in my mind with submarines, as deadly menaces in our operations in the Mediterranean. I am sure that minesweeping had been accomplished in our approaches to rivers and harbors in the UK at the end of a convoy trip, and even at our own bases in Iceland. But I did not see the minesweepers do their thing. Usually, we entered at night and I did not see much of anything, except to marvel that the Captain, the Navigator and the Quartermaster could find their way around in some very complicated water passages in the western part of the British isles.

The U.S. Navy's high command anticipated mines in the Mediterranean and its North African approaches. We had two classes of U.S. Navy sweepers, an all metal hull "fleet minesweeper" class and a smaller wooden hull class. At North Africa, I can remember the USS Raven, USS Auk and USS Osprey of the "fleet"class. One of these was commanded by LCDR Joseph Stryker, who had been a watch officer at the Naval Academy when I was a midshipman. Later, deeper into the Med, we were helped by British and French sweepers and by a large, motley, fleet of boats of mixed Mediterranean origin newly equipped with sweeping gear and pressed into service. Keeping the Tunisian War Channel clear of mines required round the clock sweeping. Moored mines, found in large fields in enemy waters in the Mediterranean, were swept by paravanes, one on each quarter of the sweeper, which streamed out from the sweeper and supported "cutters" which would cut the cables to the moored mines; most of these mines would rise to the surface, and float, still a menace but one you would occasionally see. (Those lookouts, again.) The minesweeper's service did not end with the end of the conflict in Europe. Mines, as ever present dangers, survived the end of the war in both the Atlantic and the Pacific.

The Pacific; A Situation Brief

In Chapter Fou of the book, we delved quite deeply into convoy hazards in the North Atlantic in August of 1942. In the Pacific, the great sea battles of the Coral Sea, a defeat (counted by some a strategic victory, but we lost the carrier USS Lexington), and Midway, a victory, took place in this crucial year in the same months in which the Allies debated their first big move in the Atlantic. But, the Pacific events that I most bracket with North Africa as the beginning of US counteroffensive operations, took place on Guadalcanal in August of 1942. Here, U.S. Marines took ground from the Japanese. It cost the U.s.Navy many warships.

The Japanese decided in May 1942 to build an airstrip on Guadalcanal. (That decision led to the sea battle of the Coral Sea.) Ninety miles long and thirty miles wide, this island in the British Solomons' Islands had it all-mountains, jungles, quagmires and bugs and daily rainstorms. Admiral Nimitz determined that a base from which the Japanese could raid Fiji, New Caledonia and even Australia, must be denied to them. On August 7, 1942, under General Vandegrift, 11,000 Marines began to land on Guadalcanal and 6,000 on Tulagi right alongside. On Guadalcanal, a small U.S. perimeter around the airfield was secured by nightfall. The Japanese mounted an all out suicidal assault on the Marines on Tulagi on the night of August 7. The U.S. warships supporting the amphibious landings were driven off that night by a superior Japanese force. The U.S. forces ashore were cut off from supplies and reenforcements and had to dig in each night against a series of attacks which lasted until December, 1942. After furious sea battles between U.S. and Japanese ships, the U.S. finally got the upper hand locally and Army reenforcements began to come ashore in late 1942 and early 1943. When the last Japanese evacuated in February 1943, the Marines and the Army could tote up severe losses in dead and wounded in proportion to the number of men involved. From Guadalcanal in 1942 to Okinawa in 1945, the losses would be heavy. The U.S. did not hold a decisive edge in power in the sea and land effort in the Solomons in 1942 - they eked out a victory over a stubborn foe. And the foot soldiers labored under the physical strain of weather and terrain foreign to most Americans, and under the mental strain of being outnumbered on land and at times cut off from their lifeline, the supply and reenforcement train. Nimitz made a fateful and courageous and correct decision about where to take a stand during a period in which the War for Europe would take priority. The epitaph a Marine etched on a mess kit placed on a buddy's grave in Guadalcanal's "Flanders Field" says it all.

"And when he gets to Heaven, To St. Peter he will tell: `One more Marine reporting, sir--I've served my time in Hell.'"

The Atlantic: A Situation Brief

We have dealt with actions at sea in the North Atlantic and touched on how the German submarines extended their reach to all parts of the Atlantic. The War on land in Europe was a disaster for the Allies in Western Europe. Rommel's Afrika Corps began to roll the British back toward the Suez from Libya in North Africa. After the capitulation of the French armed forces in France in 1940, a neutral French government was set up at Vichy, France, under Marshal Petain, a World War I hero. The Vichy French and the North African French, in Algeria and Morocco, and the West African French at Dakar, began a long slow dance with Germany, Britain and the US, and with the free French nationals in Britain. US military forces became involved in the Mediterranean part of this slow waltz. The French Naval Base at Toulon was under the nominal control of Vichy. It was kept in a non-threatening role to Hitler, yet its French Fleet units did not emerge to fight for him. Dancing together were French leaders who favored the Germans, leaders who tolerated the Germans, and leaders who waited for any opportunity to fight back. DeGaulle emerged in Britain as the leader of the French who had not surrendered and would not cooperate with the Germans and who would take part in covert and later overt operations against Hitler's forces in territory that Hitler actively controlled in France. The British identified with DeGaulle's objectives, to remove Hitler from his occupied territory and defeat him. But in a way too complex to cover in this story, DeGaulle was actually an impediment in the strategy the Allies practiced with "neutral" France.

When Hitler opened hostilities against Russia in mid-1941, he could no longer make territorial subjugation of French interests in North Africa a prime objective as long as these forces appeared to stay neutral. The US and Britain, after the fall of France, began a "good guy, bad guy" relationship with the French. The US was the good guy, and for the balance of 1940 and all of 1941 up until Pearl Harbor, trafficked with the French under the eyes of the Germans. For most the period there was no doubt insofar as North Atlantic convoy operations were concerned, that de facto hostilities with Germany had already begun. Roosevelt was the consummate strategist in this matter, and Churchill went along. Roosevelt, almost alone among his advisers, wanted the second front that Stalin was begging for to either begin in Western Europe in 1943, or failing that, in Africa in 1942. When the British made the strongest case that the invasion of Western Europe could not commence in 1943 and would have to be put back to 1944, the leadership discussions, political and miliary, came back to Roosevelt's idea to begin a second front in North Africa.

(Some of the reading I have done for this story suggest that North Africa was just as much Churchill's idea. Churchill knew that the top US military leaders, who favored direct assault across the channel at the latest in 1943, would argue to shift their forces to the Pacific if forceful action in the Atlantic theater did not seem to be developing. Churchill agreed with the direct assault, but in the light of previous continental defeats suffered "on his watch" with insufficient forces, wanted to wait until the cross channel effort could be made with overwhelming forces. So Churchill may have made it appear that he was `giving in' to Roosevelt by approving the North African invasion. The capture of Tobruk by Rommel probably tipped the scales finally. It was good that political leaders could argue things out and then proceed. Compared with World War I, the second great war was a model of cooperation by the Allied leadership.)

The Discussion Period Is Over

The decision to proceed on this plan was made in July 1942. Roosevelt's decision to send modest relief supplies to help both Europeans and native Africans in North Africa, cut off as they were from most manufactured goods and some commodities by commerce which emphasized military supplies, paid off. Roosevelt's courting of French political and military leaders in Africa paid off. They were a mixed bag as to their persuasions and their loyalties, but just knowing the players found the US succeeding in a role that often confounded it. Frenchmen with names like Darlan, Laval, Weygand, Boisson, Nogues and Juin appeared in important roles. I have sliced through an enormous amount of political intrigue here and would refer the reader to the early pages of Chapter I of Morrison's Volume II, Operations in North African Waters. This Volume is the second listed in the History of United States Naval Operations in World War II but actually was written before Volume I since Morison himself was embarked on the USS Brooklyn for Torch, the code name for the North African landings by the Allies. Morison likely did not want to set aside his first hand thoughts before returning to the geographically more challenging Volume I on The Battle of the Atlantic.

When France fell in 1940, Roosevelt sent Admiral Leahy as his Ambassador to the Vichy regime. After Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt recalled Leahy for "discussions" and then made the Admiral his Chief of Staff for the balance of the war. Both Morison in Volume II of his History and Anne O'Hare McCormick in the New York Times, complimented Roosevelt for buying precious time (my words) . I wonder how the press and the Congress would react if a US President today made such an ambassadorial appointment as Leahy's to the Vichy French. Would the US manage to sound one voice (almost one voice, because some isolationists were still being heard in 1940 and 1941) as our people did 55 years ago?

For, Against, and Neutral

Summarizing, the Vichy government was in control of Tunisia, Algeria and French Morocco. There were no German occupation forces in these countries and no evident DeGaullist core group. Libya, the Italian colony between Tunisia and an Egypt still under British control, was the scene of land warfare between forces of Rommel and the British General Auchinleck, who checked the Germans at the First Battle of El Alamein on July 2, 1942. Southern France, including the French Naval Base at Toulon was neutral under Vichy. Spain, with its Spanish Morocco, astride the Straits of Gibraltar, was neutral. Malta, after its heroic defense, survived to remain a critical base for the Allies. The British naval base at Gibraltar was the western anchor of Britain's Gibraltar-Suez lifeline, a lifeline that had been virtually closed since 1941. Italy, the Balkans, Greece, Crete and Libya were under Axis control. General Eisenhower would be the overall commander of the North Africa operation, with Admiral Cunningham RN as Allied Naval Commander. November 8, 1942 would be D-day.

U.S. Amphibious Forces

After a hiatus between wars, the US began a renewal of training exercises for amphibious operations in 1933 with the creation of the Fleet Marine Force, with the 2nd Marine Brigade stationed in San Diego and the 1st Marine Brigade on the Atlantic Coast. Each year from 1934, a training operation was conducted at Culebra Island east of Puerto Rico. This training included naval gunfire support. In 1941, Adm. E. J. King, CincLant, was in charge of this exercise. For the first time Higgins landing craft were used in lieu of ships' boats. In his Volume II of History of US Naval Operations in WW II, author Samuel Eliot Morison records:

"No special landing craft for tanks and vehicles had yet been constructed, but their prototype, a 100-ton steel barge with an improvised ramp, propelled by four Navy launches secured one to each corner, transported to the beach tanks swung out from the ships' holds."

" After the fall of France the 1st Marine Brigade was held in a state of readiness at Guantanamo, and expanded to the 1st Division, USMC early in 1941. A part of this division was sent to Iceland. The rest of it on 13 June 1941 was combined with the 1st Infantry Division US Army, which had already enjoyed some amphibious training as the Emergency Striking Force, commanded by Major General Holland M. Smith USMC. General Smith formed a staff of Army, Navy and Marine Corps officers and continued training. After sundry renamings and reorganizations, during which both the Marines and the 1st Division were released for other duties, this Emergency Striking Force emerged as the Amphibious Force of the Atlantic Fleet.

Amphibious Operations

There are two generic amphibious operations. One is shore to shore, which is pretty much what a substantial part of the Normandy landings turned out to be. The other is shore to ship, a transit, and then ship to shore. That describes the North African landings in 1942. In the training phase for what became TORCH, because decisions did not always "filter" down rapidly, the US personnel were training for an impending operation expected to be shore to shore. The landing craft people did not have their training objective shifted to ship to shore until late August 1942.

A further distinction occurs in loading for the ship to shore amphibious operation. The vessels can be "combat loaded" and "transport loaded". The combat loaded ships will be the first ones in action as D-day and H-hour arrived for the North African invasion. The transport loaded ships could be off loaded with boats and lighters but worked best if we secured the port so that they could go alongside a dock and unload specialty troops and cargo. Underway, moving close aboard, an escort ship's personnel could tell which ships in the convoy had been combat loaded and which transport loaded. An enemy submarine captain, through his periscope a few thousand yards away, is not likely to make such a distinction. Both types would look like promising targets.

The combat loaded ships carried landing craft, crew for the landing craft, Army personnel and the vehicles necessary in the assault phase. For TORCH, the following landing craft were used:

(1) the original Higgins boat, a 36 footer, plywood, with a a square bow, LCP (L) for Large.

(2) an LCP (R) for Ramped, 36 foot, metal; the LCPs were for 36 troops, crew of three

(3) an LCV, 36 foot, metal, for vehicles; had a larger bow ramp than the LCP (R)

(4) an LCM, for Mechanized, 50 foot, heavier metal, for one tank; an early model

The original plywood Higgins boats were holed easily on rocks and were used sparingly after the North African experience. Also, from this event on, ramps were a requirement to minimize troop exposure in the treacherous moments of hitting the beach, or shallow water, with heavy packs.

Close In Support; The Role for Destroyers

We are including only enough information in the foregoing paragraphs to cover the amphibious assault phase, which is the phase in which the destroyer played such a major part in WW II. The destroyer's role is our central theme and will be developed as the story goes along. It needs to be mentioned here that the minesweepers, in the initial phase of a landing operation, usually had a sweeping duty even closer to the enemy guns than the destroyers. Often, just to defend themselves, the fleet type minesweepers would fire back at hostile shore batteries. But their mission was to clear the area of the most substantial risk of mines so that the fire support ships could get in.

The value of the destroyer in supporting assault landings could not have been realized without the communications teams that went ashore with the assault troops. Those teams, in effect, started the computer problem for the Edison's 5"/38 cal. gun battery and its fire control systems for the four Mediterranean chapters of this tale. They furnished the initial coordinates, observed the shell impact points, and then supplied corrective spots, in, or out, so many yards, and right or left, so many yards, or mils (milliradians) if using angles.

At Little Creek, Virginia, an amphibious signal school was set up for Army Signal Corps and Navy Communications personnel. (Although it turned out that Edison fired many rounds, she was not assigned a specific shore gunfire support role in TORCH. But in covering how the communications was handled for ship to shore firing in support of troops being landed, Casablanca's successes and failures set the stage for how the ship to shore fire control party communications could be continually improved in all subsequent landing operations.) The origin of the Navy contribution came from carrier air support experience. A naval aviator, an aviation radioman, and an SCR-193 radio set mounted on a jeep constituted one naval air liaison party. There were four such for TORCH and their original task was to obtain carrier-based air support for ground forces. These teams evolved into naval gunfire support teams with a destroyer or cruiser furnishing the firepower instead of the carrier. The first radios would not stand the dousing of salt water in the "swimming" stage if the landing craft did not make it to dry beach. The jeep was a luxury too. In later Mediterranean landings, the team became mostly Army, with a spotting officer, a radioman and a man to crank the power unit to keep the radio going. When possible, an NLO or Navy Liaison Officer completed the party, These came to be called Shore Fire Control Parties, or SFCP for short.

Assembly for Torch

There were three Naval Task Forces.

The Eastern Naval Task Force, a Royal Navy operation, carried 23,000 British and 60,000 US troops, all mounted from the UK. The ground forces were commanded by Major General C.W. Ryder, USA. Object: To capture Algiers, the capital of Algeria. The Central Naval Task Force, another Royal Navy operation, carried 39,000 US ground troops, mounted from the UK. The troops were commanded by Major General L.R. Fredenhall, USA. Object: To capture Oran, Algeria. Militarily, these were larger operations than the Western Naval Task Force which proceeded to the northwest African coast on the Atlantic to take Casablanca. The Eastern and Central forces were more certain to see the Luftwaffe. They did not face a strong French Navy element though Toulon, just across the Mediterranean, contained such an element. Those interested in a full account of the part that North African operations played in World War II would want to pursue a more extensive examination of the subject than we will give here. Names like Eisenhower, Patton, Montgomery and Rommel became famous in this theater.

This story will cover the Western Naval Task Force because we were there and because the Sea Force and well as the landing forces were US operations. Landings by the three Naval Task Forces were scheduled for the same time and executed within minutes of each other.

The Western Force, to be escorted by the US Navy, carried 35,000 US troops. The Western Naval Task Force, whose duty it was to deliver the landing forces safely to the beaches, was commanded by Radm H. Kent Hewitt. Hewitt already commanded the Amphibious Force, Atlantic Fleet. From 1 September, 1942, Admiral Hewitt and his staff prepared for TORCH at the Nansemond Hotel, Ocean View, Virginia, near Norfolk. Transports Atlantic Fleet consisted of six divisions and included troop transports and cargo ships. To be embarked as personnel trained in the handling of landing craft were three thousand Navy and Coast Guardsmen from Little Creek VA and Solomons Island, Maryland.

The Western Task Force units to be put ashore would be commanded by Major General George Patton who was appointed commander of the Western Landing Force of the Army on 24 August 1942. This Force's objective was to make Morocco, with its command of the Atlantic and of the approaches to the Mediterranean an effective Allied bastion. This was also the western flank of a North Africa from which the Allies intended to expel all German forces. The core troops were initially the US Army 9th Infantry Division and units of the 2nd Armored Division. A reenforced Regiment of the 9th Infantry Division, embarked in one of the six transport divisions, was sent to Great Britain to join the 1st Infantry Division for the assault near Algiers. The 3rd Infantry Division US Army and a battalion of the 67th Armored Regiment joined the Landing Force under Patton's overall command. Intensive training at Solomons Island for day and night landings, and gunnery at Bloodsworth Island nearby were nearly every day occurrences after the first of August, 1942. Yet the time provided for this was later assessed to be about one third of the time needed.

Author Morison has summarized the challenge of amphibious operations as requiring "an organic unity rather than a temporary partnership". This was a tough challenge for the US Army and the US Navy in 1942, and very likely would be again today (1997).

I have given more space to the identification of Army units than a naval tale might require, but we will see these units as the nuclei of the Mediterranean, and later the Normandy, assault forces, time and again. The Army folk might object to my nomenclature, but these men and their leaders became the crack marines of the Atlantic/Mediterranean war.

Guadalcanal, in August 1942, was the first amphibious operation conducted by US combat forces in forty-five years. North Africa was a major jump upward in size and scope. It was bold. It was a fundamental projection of force, to have and to hold territory. The "projection" involved 4,000 miles. It also involved some "sleight of hand" efforts by three US WW I destroyers and their embarked forces to take the nature-given strengths of the defenders and turn them to our advantage.

While Germany knew that something was up, the record shows that they never figured out the intentions of the three Naval Task Forces.

The Western Naval Task Force

The Task Groups of the Western Naval Task Force assembled in US East Coast ports and in Bermuda. Once underway, Radm. Hewitt also became Commander Task Force 34. The Southern Attack Group of this force was to land at Safi which was the southernmost penetration point of the Task Force, 150 miles from Casablanca. The Northern Attack Group was to effect a landing at Mehedia, north and east of Casablanca and much closer to it. Mehedia's US ground commander did not arrive in the US TORCH planning and training area until 19 September 1942 from England, where he had been on Royal Navy Admiral Mountbattens's staff as liaison for TORCH planning. His name was Bgen Lucian K. Truscott Jr. The Northern and Southern transport groups sortieed from Norfolk on 23 October 1942. The Center Attack Group would effect landings at Fedala, closest to Casablanca. Edison was assigned to this group. This group left Norfolk on October 24, 1942. The heavy fire support warships left Casco Bay, Maine the same day. Rendezvous of these underway groups was made at sea on the 26th and the Air Group joined from Bermuda on the 28th.

Edison was part of the transport screen during the transit from Norfolk to Fedala, October 24 to November 7, 1942. Overall, there were thirty Benson class destroyers in various assignments, plus four single stackers just a year or so older than the Bensons. 4-pipers Cole, Bernadou and Dallas had special missions, and the first two had been physically modified to show no stacks at all. A detailed list showing the assignments of Western Naval Task Force destroyers is shown on page 140 of Roscoe's book on US Destroyer Operations in World War II. Battleships Massachusetts, New York and Texas, fleet carrier USS Ranger and four carriers converted from tanker hulls, and seven cruisers played important roles in the all-US Western Task Force. A minesweeping group and a minelaying group were in the force.

The USS Ranger (CV-4) and Four Converted Tankers?

In the context of 1943's Fast Carrier Task Forces, Pacific, the Ranger plus four tanker-hull converted carriers as a group sounds almost like an afterthought. It was not. Consider that the Japanese had already sunk Lexington, Yorktown, Wasp and Hornet, and damaged Saratoga and Enterprise. There were no Essex class carriers yet in the Fleet. Therefore, Ranger, Sangamon, Suwannee, Chenango, and Santee can be seen as offering the Western Naval Task Force the Navy's hard core of available carriers. Wichita, Tuscaloosa, Brooklyn, Savannah, Philadelphia, Augusta (Hewitt's flagship) and Cleveland were a formidable group of cruisers which would have been immediately welcomed by Admiral Nimitz in the Pacific. Fleet Oilers Chemung, Winooski, Housatonic, Merrimack and Kennebec were part of an important train which could fuel oil-hungry destroyers underway.

US men of war had been to North Africa's Barbary Coast shortly after the US was born. The British had dominated the navigable waters of the Mediterranean during the years of Empire.

The British Navy would spearhead the attack in the Mediterranean. The Americans would land on the Atlantic shore of Morocco. The size of the seaborne force that my eyes could see as it assembled for the convoy to Africa stretched from horizon to horizon. And, I knew from the plans, I could only see part of it. En route, Edison was part of ComDesron 13's inner screen, protecting the Center Attack Group Transports in company with destroyers Bristol, Woolsey, Tillman, Boyle and Rowan.

Define an objective and bring overwhelming force to bear.

Would the French fight? The answer turned out to be, "yes", and "no". We were to withhold fire, but when fired on, the signal "Play Ball" told us that the French were resisting. The plan has to be sound, and the leadership flexible enough to know when the plan called for improvisation. Five US subs were to reconnoiter off shore for weather and movement of local ships and forces which might impact the operations. One, the Shad was to mark the departure point for boats in the Fedala landing forces. A US destroyer sent ahead to find Shad the night before the landings could only determine that she was not there, and on the spot replaced her for this duty.

Most of these considerations never entered the mind of an Ensign on his way to Africa on a US destroyer late in 1942. They were important. Admiral Hewitt assembled 150 senior naval and military officers involved in the expedition at Norfolk on on the day before departure. Most of them were finding out for the first time what TORCH was all about. Most of the rest of us began to find out after our ships cleared Hampton Roads.

A Sea Transit Log

(Comment: At this point, beginning the escort of the transport ships to Casablanca, some with troops, some with cargo and some with oil, the author picks up an escort of his own. This is Lt. (Jg) Edward K. Meier, a shipmate in 1942, 1943 and 1944 on Edison and a lawyer from Wilmette, Illinois for the career part of his life. He is now retired in Vero Beach, Florida. Ed joined the Edison as an Ensign on 29 December 1941 and was a close friend during the time we shared on Edison. The historian's accounts of the sea journey to North Africa are skimpy and some almost completely omit the transit of this, the largest armada of its kind ever assembled for a long range voyage. Others marked the 24 Oct. - 8 Nov. 1942 trip to Casablanca as "uneventful". The reader can be the judge.

I might add that in reflecting on Ed Meier's thoughts which follow, I can see that many thoughts that did not enter my mind as an Ensign in October and November of 1942, did enter his.

All dates in this transit sequence are late October and early November, 1942. With almost no editing, then, Lt. (Jg) Meier's story.)

The 24th. Got underway at 7:30 this morning and spent the entire morning and part of the afternoon getting the convoy organized. Our group consists of about 50 ships, from battleships and carriers on down to minelayers. We have about 20 large troop transports with us, each carrying many tanks, invasion barges etc. It is the biggest aggregation I have ever seen . The Edison is patrolling the starboard bow of the inner screen and I have the mid-watch.

The 25th. A radio broadcast today reported that Admiral Darlan is now in Casablanca reviewing the French Fleet. Evidently the French have quite a sizeable fleet down there and we probably will have quite an exciting time taking the place. I have been reading an intelligence report on Casa Blanca concerning its strategic importance to the Allies, the geographical and topographical layout and defenses, the type of ships and planes to be encountered and the makeup and psychological attitude of the people residing there.

The 26th. Three large cruisers and a couple more destroyers joined our group at daybreak today. Later on this afternoon, another large force consisting of two or three battleships, three or four aircraft carriers and several more destroyers also joined us. As the picture gradually takes form, this certainly is an undertaking of tremendous dimensions. The Navy Dept. has seen to it that this is no half-baked invasion. It ought to be sufficient to overcome the resistance the French are evidently planning to make. We are all in highest hopes that we can take them by surprise and quickly overcome their resistance, but naturally it is very probable that they already have information that we are coming in which case a pitched battle will result.

We are now in the Gulf Stream and it is quite warm. I stood my watch this afternoon in shirt sleeves and the temperature in the shade was 78 degrees F. It rained intermittently, but in general it was a pleasant day.

The 27th. My thoughts are with Mom and Pop a good deal of the time and I'm hoping and praying that all is going along well with Pop. It is a week and a half now since the operation and he should soon begin to show signs of considerable improvement. But from the extent of the surgical disturbance made necessary, it is necessarily a slow painful recovery. Pop has always been so fine and regular that it is a shame that this had to happen to him, but I am sure surgery was the only way out and that he can still enjoy life despite his physical handicap.

The weather the last few days has been wonderful and the nights lovely and balmy. Station keeping in the size convoy we have is quite a trick, due mainly to the large number of escort ships and the small sectors assigned to each. Particularly at night is station keeping difficult, but fortunately we have a full moon which helps out considerably. We are now northeast of Bermuda and from information we have, a heavy force of battleships, cruisers and carriers will join us one of these days from that port.

( Comment: Ed Meier had been accustomed to the North Atlantic convoys in which three or four modern destroyers covering the entire 360 degrees around a convoy was considered a strong escort group. Also, from Bermuda for TORCH came just carriers and their screen. The battleships and cruisers had, in the main, already joined, but Admiral Hewitt's deceptive paths to North Africa required every group to make course changes designed to mask the actual destination. The groups were generally not in sight of one another, and proceeded as though each had its own destination. Author Samuel Eliot Morison, embarked on Brooklyn, stated that her pitometer log showed over 4,500 nautical miles for the 4,000 mile trip. If a cruiser's pit log showed 4,500 miles, any destroyer's log probably hit 5,000. For this reason, the "cans" fueled early in the trip and once again just before the landings so that no destroyer skipper would be feeling miserly about fuel as the action began.)

The 28th. The watches were dogged today and all in all I was on the bridge 12 hours, 00-0400, 1200-1600 and 2000-2400, besides 1 3/4 hours of general quarters. We have been having GQ every day from 9:30 to 11:15 for training purposes. The weather continues to be balmy and warm and I'm developing quite a suntan. Rain squalls, however , are very prevalent and are equally unpredictable, coming up in a moment's notice even when the sun is shining brightly. We were joined today with a task group of 4 aircraft carriers, plus additional escorting destroyers. Two converted 4-stackers, carrying commandos also joined us. These ships are heavily loaded with troops, have guns and masts removed. The plan is to run these ships up the river as far as they will go, run them aground and have the troops disembark.

(Comment: The four stackers were the Bernadou and the Cole. They had the stripped down silhouette. I believe Ed meant to note that they had "stacks and masts" removed. Each had specific objectives in the Safe landings, and the Bernadou was to nose its bow onto a beach. It was the Dallas, not stripped down, at Mehedia, which pushed its way up a shallow, twisting river for quite a ways to reach its objective. Though we will stick mostly with the Edison during the fighting period of 8-11 Nov., we will also summarize the exploits of these four stackers and some other destroyers.)

The 29th. We've surely got a real fleet with us now - 3 battleships including the new Massachusetts, about 5 to 10 cruisers and about 30 destroyers plus plenty of transports and auxiliaries. Hughes said (that is Ensign Jim Hughes, from West Roxbury, Massachusetts) we should steam right up to Berlin; but even with all this stuff we may have a tough time if the French and Germans want to put up a stiff fight.

Spent quite a bit of time today studying maps and operational plans for getting our troops ashore and bombarding shore gun emplacements. We are to go within 3 or 4 miles of shore, just north of Fedala, which is some 10 miles north of Casa Blanca. We will be the central part of 3 landing groups, one of the other two forces being north of us and the other being south of us and south of Casa Blanca. The troops after disembarking will converge on Casa Blanca.

The 30th. Today I was promoted officially to Lieutenant junior grade. Can't say that I feel like an astute naval officer but I do think I'm getting the hang of things aboard and the extra $20 per month may come in handy. The Captain (Headden) has signed the promotion papers and tomorrow Dr. Kemp will give me the necessary physical examination. All the destroyers and cruisers refueled while underway today. This is a very ticklish maneuver and it was fortunate that the sea was calm.. I have just returned from watch and I can't remember when the sea has been calmer except possibly that night last February when we made submarine attacks just about all night. A couple destroyers have had sound contacts, but it is my personal opinion that they were not submarines. The chances are however, that we will run into subs rather soon.

The 31st. Took the physical examination today and everything was found to be OK so I guess I'm a full-fledged J.G. A battle station has now been assigned to me and I will be in charge of secondary control back aft. In this capacity I will have charge of No. 3 and No. 4 guns in local control. We are now southwest of the Azores on course 135 True. The plot seems to be to head directly for Dakar and then change course north to Casa Blanca in order to throw off their defenses.

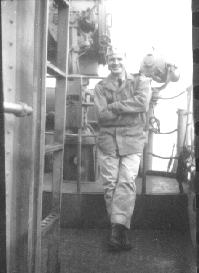

Here is a look at Ed Meier one promotion later as a full Lieutenant USNR

The 1st. Nothing of much consequence happened today and it was a beautiful warm, sunny Sunday with the temperatures ranging in the mid-70s. It was holiday routine and we did not have our usual general quarters at 9:30. Planes are constantly overhead ranging out on wide patrols during the day. At 9:00 this evening we picked up an R.D.F. bearing and on investigation by the Bristol it was found to be a Portuguese man of war operating out of the Azores. Our prearranged plan was to take neutral ships in for security, but for some reason we let this one go.

The 2nd. Stood the 4-8 watch this morning and the colors at daybreak were exquisite, ranging from deep purple thru various shades of red, blue and gray. The sea remains very calm as it has thru the entire trip. R.D.F bearings, presumably from submarines, continue to come in, and altho several of the ships have dropped depth charges, I rather doubt that any of the ships have had bona fide sound contacts.

Mail came aboard today from one of the destroyers which left the States a day after we. It was certainly good to hear from home and friends. In checking our position on the chart I find that we are considerably south of Casablanca and Fedala but only some 400 or 500 miles from the coast of Rio Diorio, Africa. Everything is going along smoothly altho hell is liable to pop loose just about any time in the form of submarines. This afternoon we took a wide sweep to starboard of the convoy to limit of visibility, returning to the convoy at dusk.

The 3rd. This afternoon we were to have towed a towing spar down the starboard side of the convoy to give the convoy target practice, but it got so rough that this was impossible. We pick up R.D.F. bearings frequently indicating that there are U-boats in the vicinity but since the bearings do not also give us range, we are helpless to track them down. We try to get cross bearings on them with other ships and in these cases we can approximate the distance and make an investigation.

The 4th. Stood the 0000-0400 watch this morning. What a grueling watch it was and the sea was plenty rough too. I had the conn at 0300 and we were supposed to have a course change from 355 degrees to 335 degrees. We changed course and seemed to be far out of position with all the other ships who had apparently not changed course. We found out later that they had canceled the change and had not notified us. It put us in a dangerous position since visibility was very poor and we had to do all our piloting by radar bearings and ranges.

( Comment: It was rare for this to occur when we were in company with an all Navy Task Force using Navy signals and communications. This did happen frequently when we were in merchant convoys using the British MERSIGS communications.

Had typhoid and tetanus shots yesterday afternoon and apparently it hit my stomach and I came very close to being sick on the bridge tonight. It is starting to get rough.

The 5th. The arm still bothers me pretty much today and the stomach to seems to be upset. I didn't get sick but came pretty darn close to it. The sea has been quite rough and this has added to my discomfort. Stood the 8-12 watch last night and the convoy came into contact with two separate Portuguese ships. Instead of taking them into a friendly port as was the prearranged plan, the boarding parties gave them instructions not to use their radios and sent them on courses so as not to interfere with our operations. I'm not quite satisfied with the way this was handled as these ships could very well give away our position and prejudice our safety and the outcome of our mission. (Author Samuel Eliot Morison stated that "one or two had prize crews placed on board to prevent their broadcasting our position.")

The 6th. We refueled this morning and now have ample fuel supply for our operations. This evening we assumed base course 116 degrees and will probably take this course right into Casablanca. I was just thinking today that 3 weeks ago next Sunday I attended Church service at the Wilmette Baptist Church with Beck and Don and day after tomorrow our assault group will attack the city of Casablanca, Africa. It's hard to step from one type of peaceful life right into the most antagonistic and offensive type, but this is war and I was lucky to get home at all. Tomorrow morning we will undoubtedly go into Condition Two watches (watch and watch, 4 on and 4 off) . From midnight on we will be at general quarters. Most of the officers and men are looking forward to this thing with a great deal of anticipation.

The 7th. We practiced our new battle stations watches all morning and at noon, the word was passed that all hands should try to get as much rest as possible before the assault. Yesterday, Dr. Kemp put out a circular letter to the effect that everyone should take a shower and put on clean clothes before a battle as a precautionary measure against infection in case of a wound. I was back in the crew's compartment this afternoon and it resembled a fraternity house before a big dance. All hands were really scrubbing down. At midnight we go to battle stations for the assault, fingers crossed.

The 8th. Boy, what a day. The first troops hit the beach about 4:00 a.m and immediately search lights were turned on by the French, but these were quickly extinguished by our machine gun fire. About 5:30 the shore batteries opened up and from then until about 9:00, our ships continuously laced the shore with heavy fire. The battleships and cruisers certainly did a job on those shore emplacements and a steady stream of fire poured from them. During this time we were out about 5 miles screening the transports. About 10:30 (a.m.) After the shore batteries had been silenced, another opened up at Fedala, which the Edison and two other destroyers silenced. We came in about 1 mile of the beach to do this. This battery had been firing on our troops just northwest of Cape Fedala and was really slicing them up.

About this time we received word that the French Army did not wish to fight. The Navy however was a different story and at 11:00, the Brooklyn, Augusta, two other cans (if it has not come up before, destroyers were also "tin cans" usually shortened to "cans") and the Edison, lit into a French cruiser and two destroyers. Our fire severely damaged them all and we came out unscathed. But about 4 other of our destroyers were damaged by shell fire from the beach.

Several shells hit quite close to us and shrapnel hit our port side. One shell sent a pillar of water skyward not more than 500 yards from our port bow. This afternoon, our cruisers severely damaged one more French cruiser and sunk or beached two destroyers. One French corvette was sunk by one of our destroyers.

We're all hoping that all goes well for our troops ashore and that they have already taken the Fedala airfield. Additional U.S. planes are due here tomorrow. Tonight we are screening the troopships which are moving close in to shore. The French Fleet has put up a gallant fight and for a while we had a real engagement.

The 9th. One French cruiser attempted to get out of Casablanca Harbor this morning and two of our cruisers drove her back in with gunfire; but other than this there was little excitement. The French Army has expressed a very cooperative attitude, but the Navy has altogether refused to discuss any peace terms. Therefore, tomorrow morning at 8:00 our battleships and cruisers will steam back and forth across the mouth of the harbor and reduce the ship and harbor installations to a shambles. We do not like to do this, but it is necessary since we need the harbor for disembarking troops and materials.

German planes were overhead today, but made no attack. Possibly tomorrow, since we heard over the radio that they did attack our ships and troops in Algiers. We are now in watch and watch which is plenty tough physically.

The 10th. Safi and Fedala fell to our forces yesterday and radio reports say that Algiers and Oran, together with their airfields fell to American and British forces. As yet we have not taken Casablanca altho city officials have already expressed their willingness to capitulate. Probably the only reason we have not already gone in is the resistance of the French Fleet and shore batteries in the harbor and vicinity. This morning, two French destroyers attempted to get out of the harbor. Immediately the Edison followed by the Augusta and 3 other destroyers piled right in at 30 knots and made a vicious attack. All in all we fired 369 rounds of 5 inch shells at them and probably seriously damaged one of them. The Edison did most of the firing and drew most of the fire from the French ships and shore batteries. They had us straddled twice and shells were dropping in the water all around us, the nearest only about 100 yards away. It was really too close for comfort, but very exciting. Later this afternoon, the French Fleet having refused our ultimatum, our dive bombers attacked the harbor and we could see huge columns of smoke from the shore batteries.

The 11th. At 7:15 this morning I was aroused from sleep to the tune of beep-beep-beep-all hands man your battle stations. Apparently one or two of the battle scarred units of the French Fleet were intending to slip out of the harbor again. This time we were all set to finish off the fleet, shore emplacements and the whole damn harbor and harbor facilities if necessary. All ships were fully ready and were starting to group for the coup de grace when word came over the TBS to cease fire. (I cannot help but notice that Ed, with this command of prose at age 27, under fire, used the word "coup de grace" for the French finale-and how about me at 77 ready with the word "finale") No one knew why, but later on over the radio, we learned that the naval authorities had reconsidered and had thrown in the sponge and were ready to confer on peace terms. It surely was about time.

This evening about 8:00, three ships were torpedoed: USS Joseph Hewes, a transport, sunk; and the USS Winooski, a tanker, and the USS Hambleton, a destroyer, damaged. They certainly caught us with our pants down and in a very cocky mood.

( Comment: My records and my memory show Hambleton as a Benson/Livermore/Bristol class destroyer. She shows in Theodore Roscoe's "Destroyer Operations in World War II" as DD 455.)

The 12th. We escorted the Hambleton as she was towed into Casablanca today and we got within a mile of the town. It is really a very pretty place, with modern buildings all very well kept. They are all white or of a light color, hence the name Casablanca. The Jean Bart and several destroyers and a cruiser and several merchantmen could be seen aground in the harbor.

This afternoon late we went into the transport area at Fedala to refuel from a tanker and at 5:45 as we were alongside her, two of the transports were torpedoed not more than 300 or 400 yards from us. General Quarters sounded and we got underway immediately. (More on this later; we left Edison men aboard that tanker in our hurried departure.) Before we could get very far another transport was hit, right under my eyes. It quivered, shook, and nearly capsized. Within 10 or 15 seconds men were climbing down the sides into the water. One ship burned all night and sank about 3:00 this morning. (Would be the 13th.)

The 13th. Today was Friday the 13th. After the torpedoing last night the entire convoy got underway. Several other destroyers and we stayed and patrolled the Fedala-Casablanca area and this noon went out to the rendezvous and escorted part of the transports back to the Casablanca harbor. This evening we started out for the remainder and will probably pick them up tomorrow morning and bring them in for unloading.

That certainly was a pitiful sight last night to see those good ships torpedoed and sunk. Tears came to my eyes to see them in their helpless condition, but this is war and it is all part of the game. It is all a matter of give and take and we can't let it get us down. This morning the entire area was strewn with wreckage of all types and oil covered the surface. It was a disheartening sight.

The 14th. At 8:00 this morning we contacted the section of the convoy which has not gone into Casablanca for unloading. We are now some 150 miles northeast of our new base and will arrive there late tomorrow morning. (We) are hoping that as soon as the cargoes are unloaded, we will head back to the States. The Captain said today that if we all don't get leave, he will put all hands on the sick list and grant sick leave.

The 15th. Patrolling station on port bow of convoy bound for Casablanca. Early this morning a supply ship the USS Electra was torpedoed and we picked up a survivor. (This is the one who was paddling a board toward New York.) For the remainder of the day we stood by her while salvage operations were conducted and about midnight, she was towed to Casablanca.

The 16th. On our usual 180 degrees, 000 degrees patrol outside Casablanca. Early this afternoon we went into the harbor and refueled. Boy, what havoc we raised in that place during the bombardment. About 10 ships are full of holes and resting on the bottom, including at least 2 cruisers and 4 destroyers. Other destroyers were sunk by us on the outside. The Edison had a pretty good hand in sinking three, one almost single handed. The battleship Jean Bart is resting on the bottom.

The town itself seems to be very nice altho the reception granted to soldiers and sailors is still very hostile. Saw "Flight Lieutenant" tonight. We are now anchored in the mouth of the harbor and scuttlebutt has it that we will return to the States tomorrow.

8-11 November 1942 ;the Author's Perspective, and Others

We will return to newly promoted Lt. (Jg) Meier for an author escort on the trip home from North Africa, a trip which had its own excitement. But, here we add a composite of a number of different observations on the shore attacks.

No Softening Planned

In all landings subsequent to Casablanca, both in the Atlantic/Mediterranean and in the Pacific theaters, extensive pre-landing bombardments were conducted to soften up the defenses. This was not done at Casablanca in 1942. The TORCH timing was even more ticklish than for the surpassingly large force landed at Normandy in early June of 1944. Three different sea forces in TORCH had been at sea for up to two weeks, in different waters and from ports a continent apart, and were to strike a shoreline over a thousand miles long. In the last four days before the Western Task Force would go ashore, the seas made up. A minelayer dropped out of formation due to excessive roll. The fifteen foot surf forecast for Morocco on the 8th would preclude landings. This was the forecast from US and British home-based meteorologists but the weather forecaster on board the Task Force opined that the storm was moving rapidly and the seas would moderate. He was right. (Two years later, General Eisenhower received such a moderating forecast for Normandy and accepted it and was right.)

Weather cooperated. By the end of the sea journey, training had brought the signaling capabilities of the Task Force to the point that, practicing radio silence, any visual signal would reach every ship within 10 minutes. (SS Contessa, left from Norfolk late, proceeded without escort, and then made the last turn to the Southern Task Group instead of its assignment to the Northern Task Group. This was corrected in time. ) Morison noted that if landing times became ragged, that French naval forces from Dakar were only three days steaming from Casablanca. (It is interesting that 10 minutes for one figure of communications merit, and three days "steaming" for the "nearness" of reenforcing French naval vessels, would be cited as pivotal time intervals for experiences in 1942, written about in 1946. )

The three Task Groups of the Western Naval Task Force, each led by their own minesweepers, and covered by their own air groups and heavy seaborne artillery, the battleships and cruisers, took position and commenced their roles. Unloading of the combat loaded transports was scheduled for midnight on the 7th, with four hours to make up into the boat lanes before departing for the beach. Earliest to reach this position was the Northern Group precisely at midnight and latest was the Southern Group fifty-three minutes later. This dark period was essential.

SG Radar Navigation Fix

A northeast set of current moved the groups off position. Author Samuel Eliot Morrison's Volume II of the History of US Naval Operations in World War II informs us that a critically important SG radar on a ship that he did not identify and that all my research has failed to identify, detected the dead reckoning navigation error while still several miles offshore. As Admiral Hewitt's command and control ship for the Western Naval Task Force, that radar could well have been on the Augusta, his flagship. Emergency turns were effected in the mother ship columns, but darkness and the unanticipated maneuvers made for some confusion for the trailing transports in the Northern and Central Task groups. The two locations were close enough to each other to be influenced by the same offshore current. As a consequence, organization of the two boat lanes for the Northern Group and the four boat lanes for the Central Group took extra time.

Dim lights ashore indicated that surprise was still with the attackers. Two accounts mentioned the pungent aroma of charcoal from Fedala, a characteristic we all noted while ashore in later months in North Africa. A change of command takes place at this point insofar as the shore bound forces are concerned. In the Center Group, Captain Emmet on the transport, Leonard Wood, took over. The destroyer sent ahead to contact the marker submarine did so, found her and reported to the Task Force Commander on Augusta. Unfortunately, the man who now most needed to know, Captain Emmet on the transport Leonard Wood, did not find the sub.

The times indicated are Greenwich. Local sunrise was 0655 with twilight almost an hour earlier. There were four boat lanes for the Center Group, at the head (south end) of which, closest to the beaches, were the Benson-class destroyers Wilkes, Swanson, Ludlow and Murphy. The lanes were generally South, to the beach. Behind Wilkes in the western lane, was the Leonard Wood, first in her column to unload. Her scout boat was to head south for Red 2, the closest of the assault beaches to Cape Fedala, following her lead destroyer, the Wilkes, which would lead the landing boat column until turned away by shallow water. Similarly, with the same 0400 lead boat landing time, the T.Jefferson's boats were to head for Red 3 to the east behind the Swanson, with a lane angle from the Red 2 lane a bit to the SSE. From west to east, the Carroll's boats were for Blue 1 and the Dickman's for Blue 2, behind Ludlow and Murphy respectively. These last three lanes were parallel and avoided rocks located at the beach in the arc east of the Wood's Red 2 beach.

At the seaward end of Cape Fedala was the Batterie des Passes, two French 75s. At the base of the cape was a pair of 100 mm guns. At Chergui, 3 miles north, Pont Blondin had a heavy battery of four 138.6 mm guns which could cover an arc from the transport area to the control destroyers to the landing beaches. Down from the town of Fedala was a mobile 75mm AA battery. The beaches were in a two mile crescent open to the sea on the north The beaches were punctuated by rocks. The 138.6 mm guns had a range of over 15,000 yards, more than matching a destroyer's effective range.

At the east end of the crescent was the Sherki headland and at the west, next to beach Red which was not to be used in the assault phase, was Cape Fedala. Just behind the Cape and Red 2 beach to the south was the town of Fedala.

The transport area can be visualized by considering the transports Leonard Wood, the Thomas Jefferson, the Carroll and the Joseph Dickman on an east to west line. Just aft of a control destroyer, each was the head of its own transport column, four ships deep extending north behind them. This group, twelve transports and three cargo ships plus a fleet oiler, defined a 2-mile square, six miles north of the beaches. They could "lie to" or anchor, at their option. While the lead transports had sufficient boats for most of their embarked assault troops, each had to borrow some boats from the transports behind for complete debarkation.

The scout boats, to mark the beaches, left first. These had five men, one in command, and a mix of Navy, or Coast Guard personnel for the boat crew, and Army enlisted men. These boats had engine silencers and a special compass. There were infrared flashlights and a radio set. The men carried submachine guns and automatics. They had to mark their beach, and anchor at a specific position. At H minus 25 minutes they were to use their flashlights seaward, and at H minus 10 they were to fire flares to identify their beach. (Two red flares would mean Red 2.) The control destroyers had to be one half mile south of their designated lane by 0200, defining the rendezvous area. On signal, each destroyer began to lead the boats in at 8 knots. Two miles off shore, the destroyers would anchor, defining the line of departure. At Captain Emmet's command, hopefully at H-hour, the assault wave boats would depart for the beach. The scout boat flash lights were now their beacon. Some lanes might have armed support boats if required. At the break of morning twilight, the destroyers would mark their lane departure points with buoys and colored streamers. Scheduled arrival time for the assault wave was 0415. It would be pitch dark and the tide would be going out. The destroyers would proceed to their designated gun fire support positions.

Our Troops Go Ashore At Fedala

It will not go down as a "textbook operation". The first line of transports began unloading on schedule. The decision to use all the small landing craft and all the tank lighters (forty four) in the initial waves, led to traffic jams in the water before departing for beaches. The task of the lead transports to load over fifty boats each, while borrowing boats two or three miles away, and have them in the water at the line of departure at 0400, would have been a daunting task even with experienced coxswains. Our boat crews for North Africa simply did not have the experience that the plan demanded. Adding to the loading difficulties, the rear of the transport columns straggled to position at the tail end of the emergency turns just past midnight and could not get the borrowed boats up to the head of the column on time. Just over three fifths of the boat lanes were populated according to plan when they left for the beach. Leonard Wood came closest with all her boats in the water before 0200 but that was not enough time for men, in the dark, to get down in loading nets to the boats and be ready to go. H-hour was postponed to 0500. The General of the 3rd Infantry Division commented in Samuel Eliot Morrison's History, "Failure of ships to arrive in the transport area, as scheduled, completely upset the timing of the boat employment plan."

All Scout Boats except the Jefferson's, which had engine trouble, were ready alongside Wood and departed at 0145. With the Wood's boat in the lead, they looked over their assigned beaches and each selected its position. They did not find out about the one hour postponement so their preliminary blinking could have been sighted by defenders. On signal from the skipper of the USS Wilkes, the destroyers moved in at the head of their first assault waves to their anchor points, with Scout Boat light flashes confirming to the destroyers (no flashing the other way) that a "follow the leader boat procession" would find the correct course. The assault waves left at 0500 and were on the beaches between 0515 and 0525. Successive landing waves came in five to ten minute intervals. Thankfully, the sea waves were negligible for the boats that actually found their assigned beaches.

Except for two boats which missed the control destroyer and landed and broke up on rocks to the east of Sherki Headland, the Blue 2 boats, at the narrowest beach under the headland, did well and some of their boats retracted before it was light and got back to their transport by 0630.

At the next beach to the west, Beach Blue, the effort did not go well. There was surf created by ledge rock. The test of seamanship here was too demanding and 18 of the 29 boats in the initial attack waves were put out of commission and five more lost in the second landing here. The US, a producer nation, was put to the test by the very heavy loss of landing craft. By day's early light on November 8, this beach presented a disheartening scene to local commanders. (To the credit of people who did not give up, salvage efforts regained some of the losses. But, not until the assault phase was over.) The Scout Boat for this beach became a total loss on Beach Red 3.

The Jefferson's troops were to go to Red 3, just west of Blue. One of Jefferson's loading nets gave way and overloaded soldiers were flung into the sea. Jefferson's Scout Boat, with its engines now working, had missed the scout boat assembly at Leonard Wood, where courses had been given out. This boat went in on her own, to a beach east of Sherki, off its assigned position about 2 miles. The Ensign in charge of the first wave had the good sense to turn away from high surf there and led his small group back to the misplaced Scout Boat and all made their way west. Again, the assault wave boats lost contact with the Scout Boat in the darkness, turned east and made a rock landing at almost 0600, three miles east of their proper position. They lost two thirds of their landing craft. The next wave landing there lost half its boats. A third wave with vehicles aboard made an unplanned landing but got ashore in good shape, though out of position. The Jefferson Scout Boat finally found Red 3, and got the Swanson, which had also gone to the wrong position, to move. Wave four went to the right place but wave five went back to the wrong beach. Out of 33 boats, Jefferson lost 17. Of the 16 which made the two way trip, six needed repairs.

Heavy defender firing began after 0600 and a hiatus in the assault landings ensued.

Wood's Scout Boat had been directed to mark the east end of Red 2, the westernmost beach for the assault phase. This position marked a reef and the assault boats were to leave their Scout Boat's marker position to their port as they made their way in. Approached by a "mystery boat", according to Morison's account, the Wood's Scout Boat let go their anchor and drifted away from their reef-marking position. The first Wood boat waves, taking their position from their scout boat's signals, turned SE and approached the beach on an oblique line and, with the confidence given by the scout boat's signals, ran full bore onto the rocks between Red 2 and Red 3. While some managed to retract, others left their troops to scramble over rocks with loss of equipment. According to Morison's account, 21 of 32 of Wood's assault phase boats were lost.

If one evaluates progress by survival of assault landing craft, the numbers lost in the initial waves were very high. None of the accounts I have read covers the resulting number of soldiers and sailors drowned or disabled. There is no account available on the loss of the soldiers' precious equipment, the tools for their own defense or for the attack at hand. In the Wood's case, as with the Jefferson, both scout boats and control destroyers were out of position.

The question arises, where was that SG radar? Did just one US Navy ship have SG radar at North Africa, and what was that ship's subsequent assignment after she first determined what the set in current had done to the initial positioning of the transport group? That SG fix was the vital information that provided the important first correction. The set in current persisted, and nearly led to disaster. The scuttlebutt at the time suggested that equipment like the SG radar was available on more than one US ship at Casablanca. Morison's History mentions the SG radar at Casablanca only once. A reason for reflecting on this matter will come up again before we are done with Casablanca in the 8-11 November 1942 period.

An assessment of the situation after the first hour at Fedala was that 3500 troops had been successfully landed by morning twilight, which marked the beginning of French resistance. Initial beachhead objectives had been secured. After the gun battles (which we will get back to after looking in on Safe and Mehedia), assault waves resumed landing at Fedala and by nightfall of the 8th, over 7000 US troops were ashore and had a pretty good handle on the ground situation at Fedala. (While accounts of the actions of the Eastern and Central Task Forces, attacking Algiers and Oran respectively, are not available in the detail that historians have provided us for Casablanca, Safe and Mehedia, the loss of landing craft in those Mediterranean landings were even more severe.)

Safi

The Southern Attack Group of the Western Task Force broke off from the main group early in the morning of the 7th. Radm Davidson on Philadelphia, the USS New York, the carrier Santee, and a number of destroyers with their transports headed for Safe, 150 miles down the West African coast from Casablanca. Converted WW I destroyers Bernadou and Cole had key roles. French Navy-manned coastal batteries defended Safe to the north and an Army battery of 155 mm guns defended to the south. Philadelphia and New York each took a position to get a firing line to those batteries. Three Benson class destroyers, Mervine, Knight and Beatty were the close in fire support for the landing parties. Destroyers Quick and Doran screened the transports and destroyers Rodman and Emmons screened Santee. With H-hour set for 0400, the two WW I 4-pipers peeled off for the harbor at 0330. Despite Mervine's hull being gashed by a Spanish fishing vessel at 2145 on the 7th, lights in the harbor suggested no alarms there.

Again, a little Scout Boat led the assault craft parade behind the converted destroyers. With assault companies of the US 47th Infantry aboard, Bernadou was to touch bottom at the head end of the small harbor and her force was to seize and to hold the harbor area. Cole would go alongside the mole and her force was to grab and secure the loading cranes and machinery. Cole was to set it up so that the transport Lakehurst could go alongside the mole and disgorge tanks which would form up ashore and head for Casablanca. North African coastal surf predictions precluded getting the tanks "wet" in single barge and ramp landings on a beach.

Bernadou was "challenged" at 0410 just short of the breakwater and gave an innocuous answer. At 0428 as Bernadou rounded the north end of the mole, a shore battery belched fire. French "75s" and machine guns raked the harbor and Bernadou announced a "Play ball" over her TBS. Her 3 inchers and her 20mm guns began to fire at gun flashes. Bernadou and Cole were straddled a number of times but Bernadou's counter fire and Mervine's 5"/38 cal. fire silenced Batterie des Passes 2000 yards north of Safe after six minutes of exchanges. Four 130 mm naval rifles on a commanding headland three miles northwest of Safe then started firing into the transport area. New York, Philadelphia, Mervine and Beatty were straddled but by 0715, this battery, Batterie Railleuse was silenced. The harbor work was going like a day at the local shipyard when Cole was asked to take the signal station, on the hill overlooking the mole, under fire because troop advance there was hampered by small arms fire. With four 3" 50 cal. shells, Cole silenced this sniper fire. All coastal batteries were knocked out by 1300 and the Lakehurst came alongside and unloaded tanks which were underway to Casablanca by the next morning with accompanying troops. French aircraft (there were 150 reported available to repulse the three landings of the Western Task Force; these planes were a distraction but they did not play a critical role) made a brief attack on the 9th but by afternoon Radm Davidson was confident enough to release New York and two high speed minesweepers to the task group at Fedala. By the evening of the 10th, Philadelphia, Knight, Cowie, Cole and Bernadou commenced a shore group escort for tanks and troops on the road to Casablanca. Sixty miles off shore, Santee was fired on by a submarine (could have been French or German, but my guess would be a German U-boat) which missed with two torpedoes.

Mehedia

This objective proved a tougher nut to crack. The 4-piper Dallas took Army Ranger troops aboard in the darkness before H-hour at 0400 on the 8th. Those men were to take the airfield at Port Lyautey. This field was a major objective of the Western Task Force. (The Douglas DC-4 aircraft was just coming into service, as a C-54 to the Army Air Force and an R5-D to the Navy. Using a route with Lyautey as its continental African terminus, this 4-engine transport plane could fly to the Azores, thence to Newfoundland and then on into a US base. The assault forces knew only that they were to take this airfield. It was nine miles upstream on the Oued Sebou. (The Sebou River. These rivers in North Africa were alternatively called Oued, or Wadi. I never understood the distinction.) The Sebou twisted and turned, was shallow, and a dredged, buoyed channel could not be expected. A river pilot was needed. Rene Malavergne, a Free Frenchman who knew the river well, assisted by the XO of the Dallas, took her upstream, while the Captain commanded Dallas' furious resistance to French Army, Navy and Legionnaire's efforts to sink her.

At 1900 on the 7th, destroyer Roe went ahead to find the US station submarine, and failing to do so, marked her own position by radar and became the beacon ship for the Northern Attack Group. Three beaches were defined for the assault phase, one 4 miles north of the Sebou estuary, one three miles below (south) the river mouth and one hugging a jetty on the south side of the entrance channel. By one hour after midnight on the 8th, the full activity of unloading was in progress with personnel and vehicles moving onto their assigned assault platforms. The Rangers came from the Susan B. Anthony and proceeded to the Dallas. By shortly after the original H-hour of 0400 (it had been postponed one hour here for the same reason as at Fedala) the three fire support destroyers were in position, Kearny to the north side of the estuary, Roe to the south, and Ericsson in the center where she could help wherever the extra fire power was needed. A stone fort was located in the estuary, and the south bank of the entrance was under the firing arcs of French 75s and a 138.6 mm battery.

At 0500 the first assault waves passed the support destroyers and had landed on their beachheads before the defenders were alerted. Rifle fire then came from the fort onto the landing craft with a searchlight illuminating them. A shore battery then zeroed in on the landing craft going to Green Beach and destroyer Eberle was directed to respond and did so with two minutes of rapid continuous fire from her 5"/38 cal battery. Green Beach landings continued. Roe was taken under fire about 0630 from a battery and making speed on various headings fired back at a range of 5,000 yards. After a short halt in firing, Roe was strafed by aircraft. Kearny and Eberle fired at aircraft strafing the landing boats and one was brought down.