- Barnstomers and Early Aviators

- Budget Flying Clubs

- Aviation Records

- VFR to IFR

- Early Airline Development

- Flight Across the Atlantic

- P-40s to Iceland

- Alaska Based Navy P2Y-1's

- Buckner Goes to Alaska

- Ship-to-Ship Battle

- Naval Flight Training

- NAS Instrument Training

- Aleutians Anti-Submarine Warfare

- Search & Rescue

- Gyros and Flight Computers

- Baseball Team Lost in Flight

- Tomcats and Boeing 777s

Part 1. An Early Airline (and some planes it flew)

Boston &Maine (B&M) Airways' 'early success began with Stinson Trimotors, then turned to Lockheed 10 & 12 Electras. Those Electras had the new Sperry gyro flight instruments that enabled flight in clouds. B&M renewed its competitive vigor by naming itself Northeast Airlines, then acquired its first Boeing 727, and became the last trunk line to be authorized in the U.S. It was then bought by Delta.

Prominent backers of Boston & Maine Airways included Senator Thomas Gore (Kansas), and Eugene Vidal, with Amelia Earhart on its Board of Directors. All covered in greater detail in book at upper left.

In Part 2. below, how Frank Gannett's Gannett Newspapers' pioneered Corporate Aviation in the 1930s. Plus, a very brief look at Live Oak Bank and Corporate Aviation in 2013. About halfway down the page.

Copyright 2013 Franklyn E. Dailey Jr.

It took a special breed of pilots to "sign on" as the first cadre in the creation of a successful airline. When this took place during aviation's own formative years, the stories left behind are remarkable indeed. These are stories of men, and in some instances, women, who were involved in the decision to create something new, and who then took the responsibility for putting form and substance into the creative ideas.

This page owes much to "Adventures of a Yellowbird," a classic book on aviation, by Capt. Robert Mudge.

Northeast Airlines did not fit the mold of other early startup airlines. It did not partake of the rail-air, rail by night and air by day, experience. And contrary to a substantial segment of executives in the passenger rail hierarchy that saw no threat from air travel, Northeast was founded as Boston & Maine Airways by rail executives, and supported by their railroad, the Boston & Maine (B&M). B&M was a relatively small railroad serving northeast states so perhaps their management were "out of the loop" of major railroading and could be excused for their boldness.

As a source of airline experience, Northeast, the last trunk airline to be formed in the United States, teaches what it took to be successful in the passenger-carrying air transport business, despite murderous competition. This airline was also among the first to be bought out (by Delta) in a consolidation that is still going on in the U.S. airline industry. Northeast Airlines' aviation learning years occurred just a few years before my own first years as a pilot, and took place in a region whose flight conditions were comparable to my initial operational tour in flying in the Aleutians. Northeast's pilots had made the transition to flying by Instrument Flight Rules (IFR), less than a decade before I took that step.

In a number of places, these pages owe recognition to a wonderful book, Adventures of a Yellowbird, by Captain Robert W. Mudge. In 1969, Branden Press, Inc., a Boston publisher, published the copy used for reference here. Branden's arrangement with author Mudge was terminated many years ago and the book is out of print. It is a persuasive inference that "Yellowbird" is the unofficial name that stuck because of the somewhat ghastly paint job on Northeast Airlines' then new Boeing 727 aircraft.

In his book, Captain Mudge tells the story of his airline with compassion and detail. His commercial flight enterprise ("carrier" is an appropriate generic term) came to be known as Northeast Airlines after shedding its earlier name, Boston and Maine Airways.

For basic perspective on the birth years of U.S. airlines, particularly on the achievement of instrument flight, the narrative in my book (see cover above) cites some of the experiences related by Mudge, who joined Northeast in 1941. He chronicled a number of events in which pilots who had joined Northeast even earlier than he, had made aviation history. Those pilots treated the events as all in a day's work. To them, their experiences were the ordinary things one had to do to make one segment of aviation into an economically successful enterprise. Their efforts did not make headlines. In fact, daring exploits in the air, in connection with a scheduled airline, were not conducive to attracting passengers. We can be thankful for pilot-authors like Robert Mudge who have left us some account of airline building.

Robert Mudge did not write as the historian might write. He did write passionately, accurately, and in sufficient detail to hold a reader's interest. It is surprising that no historian has yet come on the scene to do for aviation what an Alfred Thayer Mahan did for seapower. Mudge's book will be essential for the historians who do undertake such a challenge for aviation.

Mudge's title, "Captain," reflects the position he held with his airline, a "left seat" pilot. Left seat pilots did not exist from the beginning. The 1933 aircraft fleet operated by Boston and Maine Airways, the predecessor venture to Northeast Airlines, were Stinson Trimotors. This three-engine plane carried 10 passengers, but just one pilot, who sat in the middle behind the center engine in the nose. In my youth, I had seen pictures of Fokker Trimotors and there was even a Ford Trimotor, but I had never realized there was a Stinson Trimotor until reading Captain Mudge's book.

A photograph of this aircraft in Mudge's book shows its interior passenger cabin. Two struts, in the shape of the letter "A" without its middle bracket, were used to stiffen the interior fuselage. One had to crouch down to pass under these struts when moving fore and aft in the cabin.

Paul Larcom, who granted permission to use the archived photos in this page, is Curator of the Beverly, Massachusetts Historical Society. The Stinson Trimotor photo in the next illustration is from the Walker Transportation Collection of the Society. Close examination of this photo reveals that there are chains on the tires of this aircraft. Chains fit the airplane-as-transportation picture in the northeast winters of the 1930s.

Stinson Trimotor; B&M Airways; these got the airline going. (Stinson's interest in trimotors did not stop with this aircraft)

When reflecting on the piloting assignment in the Stinson tri-motor aircraft, it became a minor curiosity to determine if the single pilot was called "Captain" or simply, "Pilot." Both Paul Larcom at the Beverly Mass. Museum, and David Graham, an airport and air safety consultant and former Navy multiengine patrol plane pilot, are sure that the man in control was called "Pilot." Robert Mudge's "Captain" title derives from twin-engine Lockheed Electra 10 passenger planes, Boston & Maine Airways' second generation of planes. In twin-engined aircraft, the custom as originated called for the command pilot to be known as "captain" and fly from the left seat with a "co-pilot" in the right seat. The next illustration is a view from behind the pilot's seats. Perhaps, the American car and its road customs triumphed over the British motoring experience.

That lone Stinson Tri-motor pilot had a lot of eyeballing to do. In general aviation as well as in commercial air transport flying, "see, and be seen," became the motto for safe flying insofar as aircraft to aircraft collision avoidance was concerned. Cockpit visibility was never good enough for full reliance on that nostrum. Jet-age speeds further cut into its value. Though not sufficient to eliminate the possiblity of mid-air collision, "see and be seen" is still necessary.

The early Stinson pilot had poor visibility. The number of aircraft in flight at any one time, except in the immediate vicinity of airports where pilot training was being conducted, did not put as heavy a burden on cockpit visibility as flying does today.

The pilot had to be an acute listener. It was listening that informed him of the health of his engines long before engines were fully cockpit-instrumented. In the very early days, sound was also the principal indication of low airspeed and the approach of a stall.

To complete the tri-motor availability, there were Fokker Tri-motors and Ford Tri-motors. Navy pilot Malcolm Barker, who flew in FAW-4 out of NAS Whidbey Island, Washington, just before I did in 1946, provides a beautiful photo of the Ford Tri-motor below:

Ford Tri-motor

Rare photo of three 1930s high wing Trimotors, Ford Trimotor on right, Stinson Trimotor at center, and Fokker Trimotor left rear

(Photo courtesy of Bruce Sorensen, retired Northwest/Braniff pilot.)

We now move very briefly from early airline passenger flight aircraft, to an airline's capability to move passengers on days when instrument flight was required. At first, (see my book whose cover appears at top left for the time when arlines flew their pasengers by day and put them on the train for the night)

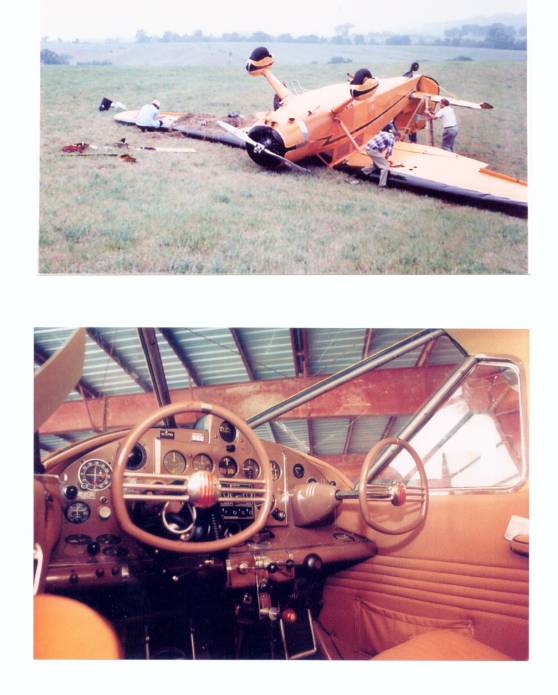

This next illustration shows the instrument panel of an early Lockheed 10 Electra. Again, the source is the Beverly, Massachusetts, Historical Society.

Lockheed Electra 10 Cockpit

The Electra's instrument configuration can be inferred from its panel. The radio frequency controls, the engine and flight surface controls, and the engine feedback indicators present a baffling panorama to a student pilot who first sees them. And indeed, this panel, even upon initial examination by the experienced pilot, might suggest a crazy quilt growth pattern. After a period of reflecting on what is there, the more practiced eye begins to find what it needs to see. Eventually a pilot gets pretty comfortable with the location of instrument indicators in front of him or her, with further dials and levers to the side, and eventually more overhead.

In later aircraft, the grouping of indicators has been greatly improved. But, this Electra 10 panel (above) tells any pilot examining aviation's progress that the Electra instrument panel represented an important step forward for safe flight and especially for safe instrument flight. In the background of the next photo at Boston's airport, we see a Stinson gullwing used by Northeast Airlines for executive trips and utility purposes. (Robert Mudge, author of "Adventures of a Yellowbird," and an early Boston & Maine/Northeast Airlines pilot, recalls flying their Stinson Reliant, a gullwing, to take senior executives and major stockholders on special trips.)

Foreground above, a view of Boston & Maine Airways' Lockheed 10 Electra loading passengers. Photo again courtesy of the Beverly Massachusetts Historical Society. The 10 and 12 Electras, each with their own series of alphabet modifications, A's, B's even E's, were prominent in early airline development. As shown earlier, these models enabled their pilots to fly schedules that occasionally required instrument flying, a necessity if "schedules" were to mean something. Trains were still the competition and trains met schedules. Amelia Earhart and her navigator disappeared over the Pacific flying an aircraft like this. We will see her shortly, in a rare photo.

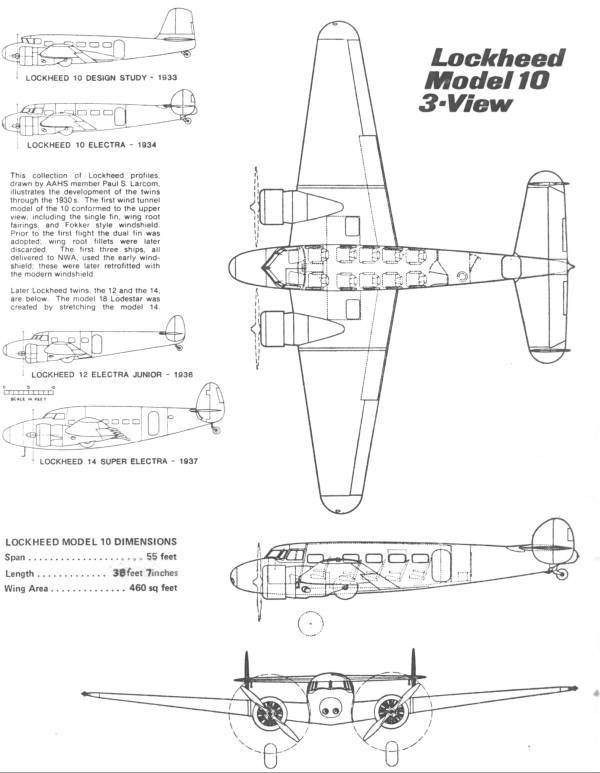

Let's take a pause here and take a quick look at Lockheed in the 1930s. First an outline drawing of the Model 10.

Above, the Lockheed 10 Electra in outline form. 1930's Electras were put in service in the nascent airline industry, and by such pioneering aviators as Amelia Earhart.

The next phase in airline growth, "revenue-positive," can be credited to Douglas, beginning with its famed DC-3. This aircraft not only had the instruments for instrument flight, it had passenger capacity, and 'boots' on the leading edge of its control surfaces, to fly through icing conditions. The 'all-weather' aircraft age had begun. (My only personal contact with Douglas hierarchy was my collaboration with famed engineer Ed Heinaman for getting the Bomb Bays of the A-3D and F4Ds configured for nuclear weapons. But that is another story for a later era.)

Here ends one fast trip through early airline developmnet with a view of some of the hardware that assisted. It took more than hardware. It took people who were willing to venture.

Here are some thoughts on the human component in airline development:

Captain Robert Mudge begins Chapter One of his story, "Adventures of a Yellowbird" ('Yellowbird' refers to Northeast Arilines' then new Boeing 727 aircraft, painted yellow, to begin trunkline service from Boston to Florida) with this compelling sentence.

"It is perhaps the world's good fortune that the road beyond our dreams lies obscure before us as we start out along the path to fulfillment."

In its "Summa Simplified", the Confraternity of the Most Precious Blood introduces the words of Thomas Aquinas as follows:

"The road that stretches before the feet of a man is a challenge to his heart long before it tests the strength of his legs. Our destiny is to run to the edge of the world and beyond, off into the darkness: sure for all our helplessness, strong for all our weakness, gaily in love for all the pressures on our hearts."

While Captain Mudge's words are his own, and my favorite quotation from St. Thomas is borrowed, I can see that Mudge and I approached the subject of flying with a respect for the unknown and faith that "a path to fulfillment" existed.

Here is a passage on "pilot judgment" from Captain Robert Mudge's remarkable book.

"Flying was news in those days. (1933) It was explained carefully (in the news) that the Boston and Maine Airways had rules of safety which forbade flying in such weather. (fog) It was comforting, of course, for the public to feel the airline was governed by such a rigid set of rules; but this was far from the truth. Rules, of course, did exist; but they were simply the rules that each pilot, individually, had learned by himself. The airline was run on pilot judgment - and that was all. Rules would come, but only slowly and as experience demanded. For now, today, the rules of operations were only vaguely outlined in the minds of Anderson and Bean. (Anderson and Bean came aboard at the behest of a pilot named Collins, who helped found the airline.) Vague though they (the rules) may have been, they worked."

Yellowbird pilots would be among the first to fly the North Atlantic rim in Operation Bolero covered in a chapter in the book pictured above. They were helping move aircraft and supplies to Prestwick, Scotland, to support the Britsh war effort against Axis powers. My own first operational flight duty occurred in the North Pacific rim. Our Aleutian pilot-teachers, the Patrol Plane Commanders (PPCs) on my initial operational tour in 1946 after receiving my Naval Aviator's wings, came from multi-engine ASW flight squadrons in World War II. Those squadrons operated from bases in Newfoundland, Labrador, Greenland, Iceland, Scotland and England (Dunkeswell, England for example) and the Azores. In school terminology, those Northeast Airlines pilots along with World War II's class of military pilots, could be viewed as being "a class ahead of me." Many of those pilots accumulated sub polar flight hours on flight schedules intensified by war. In the early experiences that characterized this period of rapid advances in aviation, there was still a lot of "learning by doing." We will shortly encounter some examples.

Yellowbird's.predecessor airline began its life in commercial aviation flying out of northeast cities like Boston, Portland and Bangor in Maine and White River Junction in Vermont. Then, returning the favor of the World War I pilot base that had inspired and instructed its pilots, Northeast Airlines, under contract, extended its air transport flight capabilities to Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, Labrador, Greenland, Iceland, and Prestwick, Scotland, all in preparation for U.S. participation in World War II. These second-generation pilots, their stewardesses, their base support crews and their investors, evolved into a globally experienced Northeast Airlines. With no little pride, I note that in the last aviation squadron to which I was assigned as Instrument Flight Instructor (IFIS), in 1962, at NAS South Weymouth, Massachusetts, a number of the "weekend warrior" reservists were regular Northeast Airlines pilots. I have saved the record of my final Navy patrol plane instrument flight-check in a P2V-5F Lockheed Neptune aircraft. That instrument flight check was conducted by N.E. Marston, a Northeast captain at the time.

Commercial airlines maintain schedules. When weather turns violent or destinations and alternates are below weather minimums, airlines may delay flights but they rarely cancel them outright. After several decades of flights so regularly on time that they were taken for granted, many news stories told of airline flight cancellations that reached all time highs in 1999 and 2000. Airline pilots and planes in the last decade of the 20th century have been over scheduled or scheduled too tightly to allow for system delays. Weather, blame it on El Nino or La Nina, plus all time records for numbers of flights and passengers, an aging air traffic control system, and too few "gates" and runways at airports, added up to an air traffic control system that had become overloaded. Delays or cancellations were the result. But by and large, over a fifty-year period from 1945-1995, U.S. airlines have maintained flight schedules. Airline pilots and other flight crew members have not had the option to decide that flying this particular day to this particular destination is something they did not care to do.

Commercial flying has many parallels in military aviation. U.S. military reconnaissance aircraft operations and U.S. military air transport operations have also been performed to high standards of mission execution. A Flight Officer in a military aviation squadron reports to an Operations Officer for the squadron. This structure does not lightly accept excuses for not taking off on an assigned mission. In 1946, in my Aleutian flying assignments, a severe ear infection could keep a pilot on the ground. (My own piloting experience never included a pressurized military plane.) A substitute pilot or a complete substitute crew could be assigned but the mission was usually launched. I flew a deployment in Alaska as copilot for my Commanding Officer, Ed Hogan, then a Navy Lieutenant Commander. He filled half the dresser top in his room in the Bachelor Officer Quarters with ear medicines. His ears were always in pain in flight, both climbing and descending, but he never missed a flight.

The record of civil aviation that I most admire is the maintenance, with safety, of its regular schedules. Their "backup" in terms of pilots, crews and equipment set a mission execution standard that military aviation can only applaud. Both the U.S. Navy and the U.S. Army Air Corps have had transport counterparts to civil aviation. These were, respectively, the Naval Air Transport Service (NATS) and the Military Air Transport Service (MATS), the latter an outgrowth of the Air Force's Air Transport Command. Those organizations maintained schedules comparable to their commercial aviation counterparts, with the added challenge of many out-of -the-way destinations.

Military flying for patrol or reconnaissance cannot match the tight schedules of commercial transport aviation and does not match airline schedule completion norms. Operational military flying done for patrol or reconnaissance involves weapons systems and electronic surveillance demands that civil aviation does not face. Added to these requirements in military aviation is "mission creep" which often becomes "mission leap." The next mission you might have to fly would have no counterpart in aviation history. In Alaska, my squadron was sent north in 1947 to escort the ships of PET Four to Point Barrow on Alaska's north coast during its brief summer of long days. "PET Four" stood for Petroleum District Four, in the U.S. federal government inventory of its precious oil reserves. Keeping ships and their drilling platform equipment clear of ice fields meant long hours for our PB4Y-2 Privateer aircraft. The landing field at Point Barrow, Alaska, was too small for our aircraft to land on, so a temporary home base was at best hours of flying away.

Orders to perform this air escort duty came to our squadron with no prior warning. The PET Four ships were on their way. Do your duty. It was not heroic in any way but it is another example of how military aviation is different from civil aviation.

Keeping to the schedule has involved a passionate commitment in commercial airline operations. With just a few intrepid passengers to satisfy in its very early days, that schedule was the focus of everyone in the organization, and the responsibility ultimately of the pilots. Prior to the availability of radio aids to navigation on the ground and in the aircraft, an early method for holding schedule in flying required the pilot to memorize every detail of the surface over which the flight had to be conducted to reach its destination. This was an early form of "instrument flying." Such a characterization might draw a raised eyebrow from those who later participated in more rigorously defined, and more technologically implemented, instrument flight.

Pilots and planes and inflight instruments and ground navigation aids, and then, putting it all together:

Pilots of those early scheduled commercial flights used their studied, encyclopedic memories of terrain, bodies of water, buildings, farms, and railroad tracks as their radio beam. They had to maintain flight schedules before the radio beam became available to act as a precisely defined flight path in its constantly "on" condition. Instrument flight checks were not given to commercial airline pilots until 1933. The radio beam did not become the widely available definition of U.S. airways until well into the 1930s.

The radio beam was the bridge that took commercial aviation from its formative years to its growth years in which a successful point to point flight could be scheduled and almost taken for granted. The technology and its application were not available to Northeast Airlines in its formative years. Since the low frequency airways radio "beam" became the basic radio aid for aviation, and therefore the essential element on which instrument flying depended, I am going to describe it here.

From radio transmitters liberally placed about the U.S., each with a carrier frequency in the hundreds of kilcocycles, the Morse Code letter, "A," dit dah, and the Morse Code letter, "N," dah dit, were broadcast into alternate quadrants by each pair of a set of four antennae. When the pilot could hear a steady tone in the speaker in his headphones, he knew it was the merging of the dah dit and the dit dah sound. When he or she could no longer hear a discrete A or a discrete N, it meant that the aircraft was on one of the four "beams" defined by the station. That beam corresponded to a path in the sky directly over an invariant path on the ground. Further out, the path was wider, and further in, the path narrowed, until over the station itself, the path converged to a point. Those radio beams created by the set of four antennae, functioned as "memory" that would be superior to any human memory of earth features, and functioned whether or not the human could see the earth below. Illustration 12 later in the story shows these beams in graphic form.

One important facet of the low frequency radio range was its station identification. After tuning to the correct frequency, a pilot would confirm that he was tuned to the station he needed by listening for its "call letters." This consisted of a repeated Morse Code aural broadcast of three letters, a feature of all the under-550 kilocycle airways radio stations of that era whether used for communications alone, for non-directional navigation beacons, or for radio range stations with their four beams. The earliest example of a "call letter" identification that I can personally recall was Radio Annapolis, with its letters NSS. Radio Annapolis was a Navy communication station. Air navigation radio range stations would regularly interrupt their "A" and "N" sector code broadcasts to broadcast their call letters for identification purposes.

Before the installation of these early radio navigation aids, and the airways system that these radio stations defned, pilots would maintain Visual Flight Rules and detour around clouds. If flying over land or water, above which the sky was partly overcast, pilots might get only an occasional glimpse of landmarks below. That brief glimpse had to supply vital information. If that undercast had fewer and fewer "breaks" in the clouds through which ground contact could be maintained, the wise pilot would go down through one of the breaks and fly 100% in "contact" with the ground even if his aircraft's altitude became uncomfortably low. Calling to stations ahead, pilots could get weather information, one element of which was "cloud cover." A cloud cover of "five" meant an overcast in which five tenths of the sky was obscured. At five or above, the pilot would begin to seriously consider getting down below the cloud cover.

In a burst of change, much of which occurred in a brief four or five-year period, the following "aids" were given to pilots. In the cockpit, an early addition was the "turn needle," a flight control instrument with an accurate response to a flight control movement but one which required a very considered interpretation of what it did and did not tell the pilot. Shortly thereafter, that needle indicator was combined with a ball in the lower arc of the round indicator, into an instrument called "needle-ball" by some and "turn and bank" by others. The turn needle indicated if an aircraft was turning. If one kept the ball in the bottom of the instrument centered by proper application of rudder, the turn of the aircraft would be aerodynamically coordinated, that is, no "slip" and no "skid." In a flight fully obscured by clouds, where the pilot had no visual reference, the pilot could keep the aircraft from turning by keeping the needle and the ball centered. Or, one could make an intentional turn, say a "one needle width" turn, holding the ball centered for coordinated flight. A pilot trained to use this information could maintain a modest turn rate.

The needle indicator was actually the first instrument installed on the pilot's instrument panel whose intelligence was derived from a gyroscope. Its function depended on a gyro characteristic called, "precession." The pilot did not need to know that. He or she did need to understand that the use of the needle in instrument conditions to maintain level, controlled flight, required extraordinary concentration and an ability to steadfastly disregard false interpretations that might derive from what the human body might "feel" was happening.

When the "artificial horizon" instrument came into use somewhat later, the use of needle-ball as the sole aid to controlled turning, a challenging process at best, faded into history for most pilots, though keeping the "ball centered" remained good technique. In addition to its indication of the turn condition of the aircraft, the artificial horizon provided a second piece of essential information. The device told the pilot whether his aircraft was nose down or nose up, and by inference, whether it was climbing or descending. This essential information was quite difficult to obtain in a timely fashion with needle-ball flying. Before the availability of an artificial horizon, one had to use two other instruments, the altimeter, and the "rate of climb" indicator, to infer gaining or losing altitude. Rate-of-climb devices had very jumpy needle indicators.

The airspeed indicator had come earlier. It improved dramatically on the determination of airspeed, an essential piece of flight information. Before the airspeed indicator and its pitot tube sensor on the plane's forward fuselage, one method to infer airspeed was by listening to the sound (pitch) of the wind past the wing struts. And when airspeed fell close to stall speed, the experienced pilot had to quickly recognize the feel of an aircraft entering the stall condition.

With a rate of climb or descent needle, and a conscientiously updated "setting" of the pressure altimeter, the pilot could maintain flight in clouds using needle-ball flying. A calibrated magnetic compass could help him hold a prescribed course and proceed from one point to another. Actual wind drift differing from predicted wind drift required a peek at the ground below to determine an actual "drift angle" and then apply that drift angle properly to correct the plane's heading in order to hold the prescribed course.

The ability to get from takeoff field to landing field while maintaining the aircraft in level flight improved day by day, flight by flight. Regularity of flight departures led to retention of dedicated passengers. Mail contracts, when added to passenger revenues, provided additional income from the U.S. Post Office Department. The combination gave the early airline a margin, though tight, of revenues above costs. Mail subsidies for airlines were a throwback to early transatlantic shipping days. Cunard ocean-going ships made a priority of His or Her Majesty's mail, taking passengers only when the mail requirements had been met.

The pilots who transported passengers for pay were eager to obtain the technical improvements and flying skills that would help them maintain flight under instrument conditions. They had a hands-on appreciation for how their rudimentary disciplines for maintaining flight in clouds needed to be improved. These pilots set and met their own standards for meeting a flight schedule while reducing risk to passenger, pilot and aircraft.

When the fog rolled into the landing field, the early airline companies saw to it that a telephone connection to a telegraph system operator was available at both departure and destination airports. The pilot eyeing his scheduled departure time could be notified in sufficient time to delay his departure until conditions improved. There was someone in charge in actual practice even if there had yet to appear a man with a title and all details of his responsibility spelled out on paper. The early pilots with a healthy respect for weather impediments to safe flight were smart enough to heed the order to delay. Those that were not smart enough to respond to cautionary signals became casualties. The process was self-cleansing.

Before proceeding further into the progress of instrument flying in U.S. aviation, let me mention three other challenges to safe flight that received some prime attention in the emergent period of modern aviation. The first is icing. Icing on the wings and on the propellers would lead to loss of lift or thrust and a crash. No answers were immediately at hand at the beginning of the 1930s. Icing on the wings, if not observed visually by the pilot, would quickly become noticeable on the flight controls. Propeller icing resulted in loss of thrust and its effect was additive to the effect of wing icing. Concentrated attention to the flight controls would not provide an answer. Changing the rpm (revolutions per minute) of the propellers could help throw off the ice. Maintaining higher airspeed by adding engine power was an initial recourse for the loss of lift due to wing icing but eventually the loss of lift could become a problem that no amount of skill with engine or flight controls could overcome. The answers to icing challenges came in four "systems" over a period of time. For the flight surfaces, these came firstas wing and vertical stabilizer leading edge deicing systems andthen wing heat over the whole surface. For propellers, first came alcohol deicers and then electric propeller heat. Where relevant to a flight situation encountered later in the story, these solutions will be covered in a bit more detail.

The next two challenges each resulted in an emergency landing by a Stinson Trimotor belonging to Boston and Maine Airways in its founding year of operation. One shut down all three engines and the pilot made immediate and successful preparations for an emergency landing on a farm. The culprit was carburetor icing. It can occur in clear air on an ideal day and in any and all forms of cloud condition. There was in Boston and Maine Airways' formative years no answer for carburetor icing with the Stinson Trimotor aircraft. The ultimate solution for Boston and Maine Airways was to add an important requirement to the list of "must-have" features required of any new replacement aircraft. That was the feature of "carburetor heat."

A second emergency landing brought to light a problem that caused a B&M Airways Stinson to lose two of its three engines. In this incident, another farmer witnessed a bumpy, but safe, landing. The diagnosis: contaminated fuel. These pioneer scheduled airline pilots knew where their pay came from. These men were money savers. Their sustained employment depended on keeping revenues above costs. The pilots often saved money by running aviation fuel from the main tank for takeoff, and switching to automobile fuel from other tanks when leveled off in a cruising flight condition. In this emergency landing incident, there was no way to determine where the contaminated fuel had come from. The airline immediately instituted a new practice. The two full containers of aviation fuel kept in the red painted barrels at each of the served airports were dumped and refilled every six months.

"The Lamp" is a publication of ExxonMobil. The Spring 2001 issue contained some eye-opening numbers. Exxon supplies one fifth of the world's consumption of aviation fuel on any given day. 700 airports in 86 countries. 25 million gallons sold every day. From 45,000 gallons of jet fuel in one Boeing 747, to 5 liters of aviation gas in a 1909 Bleriot for an air show. A picture caption on page 6 of that issue of The Lamp was quite revealing. "Crew Chief Mario da Silva runs a fuel-quality test at Guarulhos Airport in Sao Paulo, Brazil, the busiest airport in South America. He matches a color code on the card with the color of a jet fuel sample." In the photo reproduction, the colors being compared all look gray in the illustration supplied. The color swatches on the card look, respectively, more gray, less gray, and hopefully, just the right gray. This is the end of a sophisticated fuel delivery chain, so the crew chief was really looking for an outlandishly wrong color. Still, I would have expected a far better method than color swatches in the 21st century. The other data in the article are more reassuring, such as "less than 1 milligram of solids per liter" and "less than 30 parts per million of water." Those are measurable contaminants without depending on any one human being's color perception capability.

In the early days of jet flying, the airline industry and the military services operated a mix of prop planes, requiring aviation gasolines of various octane ratings, and jets that required jet fuel, a close relative to kerosene. Instances of aircraft being fueled with the wrong fuel did occur and a crash was the usual result. Even a prop plane could be fueled with the wrong grade of aviation octane gasoline.

One day in 1952, I was assigned to fly an F8F Bearcat to NAS Niagara Falls New York on hurricane evacuation. Weather in the northeast was poor and the F8F was not an instrument flight certified plane. So, I flew north using ground references, cross checking with radio beams in poor visiblity areas by using my low frequency radio range receiver. I recall passing over the Chemung County airport near Elmira, New York and then turning west to Niagara Falls. Upon landing there, I discovered that the Niagara Falls Naval Air Station did not stock the 115/145 aviation gasoline that my particular model of the Pratt & Whitney R-2800 engine required. I had about a half tank of that "hi-test" fuel left in my main tank. I filled the belly tank with 100/130 octane fuel and resolved to return to Chincoteague by using the unadulterated hi test in the main tank for takeoff, without crossfeed. Then, when I got leveled off at altitude, I would shift to the belly tank with crossfeed and let the lower octane mix with the higher octane gas remaining in the main tank. Two days of waiting for the storm to pass ensued, and then I took off for home on a Sunday morning. Locally, the Niagara Frontier had about 10,000 feet of solid overcast. I obtained a flight plan for "five on top" which meant I could fly back to NAS Chincoteague in the clear, 500 feet above any overcast. The F8F climbs pretty fast (it held the world record to 10,000 feet early in its career) and I was relieved to break out on top a few minutes after takekoff. Then I shifted to the belly tank which would give me just over one hour of flight in the level cruise condition. The weather was such that I could fly airways on a fairly direct route home. Alas, I had not done all of my homework. Near Philadephia, the undercast disappeared and then while I was almost directly over the Friendship Airport in Baltimore (now, BWI for Baltimore Washington International) my engine quit cold. On our over water, drone control flights in the F8F, we were warned to manage gas so that we did not risk losing power at low altitude because the R-2800 engine used up a bit of altitude while the prop windmilled the engine to a re-start. Lucky that my "five on top" had put me at nearly ten thousand feet. I dropped nearly four thousand feet getting that engine going again. Part of the time was used figuring out what I had done wrong. Which was simply, that the belly tank was not only running the engine, but was filling the main tank at the same time. The F8F did not glide very well. I did not have the contented hour-plus minutes at cruise altitude that a belly tank would have given with a full main tank, but a very abbreviated, hour-minus minutes before the belly tank was empty. There then ensued a few anxious moments before the engine was re-empowered. I looked around to see if anyone had been looking and made my way without broadcast of any kind back across the Chesapeake Bay to NAS Chincoteague, Virginia. Early Sunday mornings in 1952 were still good times to be flying. Not too many folks around. The importance of fuel management was brought home to me.

A Naval Academy classmate of mine, Spence Ziegler, was sent with a crew from our rear base at NAS Whidbey Island, Washington, to Arizona to pick up a rehabilitated Privateer and bring it on up to our squadron. The plane, along with thousands of others, had been parked in the open sun waiting for an occasional call back to active duty, or to the scrap heap. Based on European combat experience, these four engine planes had been equipped with self-sealing gas tanks so that a bullet in the tank would not force them down due to fuel starvation. The flight from Arizona to Whidbey Island, Washington was an easy non-stop flight for this plane and its crew. Just as Spence's plane proceeded into northern California on its flight up the coast, one engine after another sputtered and quit. Spence and his crew came over the runway threshold on an emergency landing at Redding, California, with just one engine still providing thrust. Post mortem? The self-sealing tanks had been in the desert so long that they had deteriorated and contaminated the 100/130-octane gasoline so much that the engines would no longer function. Except for leaks, inspecting those tanks in greater detail up to the time of that incident had not been on the preflight check.

Early pilots learned to be kind to their aircraft engine. Fuel of a proper, controlled, quality, needed to be used for an aircraft just as it had been for an automobile. Prudent use of the fuel, called fuel management in an aircraft, had a good payoff just as with a car. The consequences of poor fuel management in an airplane could be more punishing than running out of gas in a car. Both had internal combustion engines and both had spark plugs. Optimum firing of the plugs kept the engines running smoothly. The aircraft engine had more redundancy, a dual ignition, with "right" and "left" magnetos to check before returning the switch to "both" for takeoff.

So, here are some pre-flight checks that served well in the propeller era. Drain water from the fuel sumps until you're sure it is all gas. Check oil sumps for signs of bearing metal (shiny) or metal particles attracted to the magnet on the inside of the cover. Remove pitot tube cover. Remove battens from control surfaces. For Pratt & Whitney R-2800 engines particularly, pull the propeller through a couple of rotations by hand. The master cylinder is on the bottom and if oil runs by the rings and collects in the head chamber, the piston rod can snap, or in a less likely event the rod may go through the piston head. Both sequences are bad. The general term is called "hydraulic-ing", and refers to the incompressibility of fluids. It occurs most often when the engine is started without a manual pull-through procedure. The damage may not show itself until the plane takes off and if it shows itself during takeoff, the aircraft and its occupant(s) are in great danger.

Robert Mudge wrote in "Adventures of a Yellowbird " that Boston and Maine Airways' year of 1933-34 was by far its most crucial. There was 'a north of' Boston, south of Boston' dichotomy. B&M Airways had pledged its future to passenger traffic generation north of Boston, at first to Portland and Bangor in Maine but eventually to a comprehensive route structure serving Yankees who were willing to take some extra risk to make their time more effective.

(Part 2. Corporate Aviation begins after this next segment)

Robert Mudge's book includes anecdotes of how the new airline attracted passengers. Amelia Earhart was an important operative for Boston and Maine Airways in attracting early passengers. Interestingly, she did not fly for B&M Airways, but she did promotion for them.

In the next photo from the Beverly, Massachusetts Historical Society collection, we see Amelia with a number of ladies. She would accompany such groups on short flights over the then short routes of Boston & Maine Airways. If she got the ladies comfortable with flight, the ladies would then approve flight for the family breadwinners, the husbands. Completely logical thinking on the part of all those ladies, including Amelia whose idea it was. Incidentally, the Lockheed 10 Electra in the foreground of the earlier photo on this page is very similar to the Electra in which Amelia and her navigator were lost on the flight across the western Pacific.

Ladies fly, including Amelia

The photo was taken at Bangor, Maine on August 12, 1934. Amelia Earhart is standing at the left. Dispatcher Thomas Gore of Boston & Maine Airways is the man in the picture. The aircraft is the Stinson SM-6000, the Trimotor.

It is instructive from Mudge's story to learn how the airline kept its growing trickle of early passengers coming back. He emphasized the reliability of the flight schedule. The airline introduced delays when it was prudent to do so to await improved weather conditions but they did not cancel many flights.

The first pilot aboard was named Collins. He had earlier been a contract mail pilot. The next hire was a pilot named Anderson. Collins became the pilot in the front office and Anderson's role was to be the pilot in operations. To Anderson fell the learning, followed by the teaching, responsibility, for safe piloting and to Anderson fell the challenge to recognize change and to make the proper accommodations to change. Anderson had to confront New England weather, its land originating challenges and its sea originating challenges.

Airlines operating to the south of New England were buying new, twin-engine, all metal construction aircraft with retractable gear, landing lights, radios and flight-in-cloud instruments. Those early Lockheed Electras were rapidly entering service, configured with their advanced features.

The Stinson Trimotors flown by Boston and Maine Airways dated from an earlier aircraft generation. While the Stinson pilot's instrument panel was beginning to have part of the set of flight instruments needed for instrument flying, the ground over which they would fly had no radio aids and their landing fields had no lights. Many fields had only a grass surface. North of Boston, not even a light beacon system had been installed. This airline was a daytime operation. Its planes were configured for the environment the airline had chosen to make its own. Fortunately, the Trimotor proved adaptable to the special conditions encountered because enroute and destination weather forecasting, and the communication of existing weather conditions were both still in a primitive stage.

Captain Mudge put it this way in his Adventures of a Yellowbird: "The Boston and Maine pilots were professionals who had learned to approach New England weather slowly and carefully. At first they retreated, ....and watched and thought. Then they began to approach more closely, observing all the while, not getting too close, for it might kill them - but as close as they felt safe - to see what made it tick. They learned to probe, while in their back pockets they kept in mind a sure way of getting out if they had to......Good weather flights became practice missions for bad weather."

New pilots had to be checked out in the airline world of 1934 just as they have to be checked out today. Not many pilots got their Boston and Maine Airways check flight on a trip quite like that experienced by Stafford A. Short. He had flown with Andy Bean in an earlier flight enterprise. Bean had been the third or fourth Boston & Maine Airways pilot to come aboard and Short elected to get his checkout with Bean on a run from Boston to Burlington, VT. With 100% cloud coverage and limited visibility, Bean elected to take the Stinson Trimotor off from Boston's airport, heading east into a wind off the ocean. Short crouched just behind Bean. As the plane ascended, it flew into solid fog. The only option Bean had was to try to get some altitude

The situation now involved two pilots, neither instrument qualified, in a plane that was not instrument qualified. But, they were in the soup. As pilot, and author, Mudge described it,

"He (Bean) hung on as best he could-trying not to turn either way and keeping his eye constantly on the turn (needle) indicator in the center of his panel. He really didn't trust it very much; it was a new instrument he had never really used before; but at a time like this, it was all he had. Slowly and gently he eased the wheel back to gain precious altitude."

"Bean had concentrated intently on the new turn indicator, and managed to hold a straight course. After a rather short climb, he had broken out on top of the fog. There were no breaks in the clouds visible anywhere....Turning north, he steered a compass course toward Concord (New Hampshire) in hopes that he could find some breaks in the clouds near there. After about 35 minutes flying, he figured he should have been over Concord, but he saw nothing, so headed for White River Junction (Vermont). Holding this course about 30 minutes, still no sign of the ground. Turning right to a north heading again, he flew toward what he hoped would be Montpelier (Vermont). A few minutes after making this turn, he saw a break in the clouds and spotted a town. ....(He) recognized it as Middlebury (Vermont)..."

Concluding this flight meant dropping down beneath the overcast and making course toward Montpelier where they landed. That wind must have been pretty strong. Looking for Montpelier and finding Middlebury is a testimony to Bean's confidence in his ground recognition because while the distance covered was checking out reasonably well, the angular divergence between Montpelier and Middlebury from White River Junction is over 45 degrees! The last line of Mudge's account of this flight episode states, "Short was now qualified over the route."

On page 84 of Robert Mudge's Adventures of a Yellowbird, one finds an early tabulation of instrument flight landing minimums for Boston, and its Maine destinations of Portland, Augusta, Waterville, and Bangor. If runway lights were available, a night minimum was published. For Boston, in daylight hours, the minimums were ceiling 300 feet, visibility 2 miles and at night, ceiling 600 feet, visibility 4 miles. Keep in mind, that Boston & Maine Airways was not instrument-equipped and those numbers were for aircraft and pilots that were instrument qualified.

Andy Bean had demonstrated by his self-taught, on- the-job learning, that he was qualified for takeoff and for enroute instrument flight. He would need a better aircraft, and radio navigation ground aids to complete the destination instrument qualification. To get to a landing at Montpelier, Bean had called on his earlier skills of detailed recognition of ground features and their geographic relationship to each other.

The early days were aviation's days of 'learn by doing.' As with most human acquired skills, the idea of accumulating these experiences and putting them into a program of 'learn before doing' would soon take hold. "Ground school" was an aviation idea before the automobile driver training schools came along for automobiles. The Link Trainer evolved from the efforts of a man and his company in Binghamton, New York, to provide some feel, before actual flight, for the relationship between an aircraft's controls and its instrument's indications.

The complete mastery of all but the cruelest weather conditions came rapidly for the newly named Northeast Airlines, successor to Boston and Maine Airways. By World War II, with their extensive knowledge of northward flight, Northeast would be a leading airline in all aspects of instrument and cold weather flight operations. As part of this experience, Northeast undertook contract flights for the military, added new planes equipped for weather and instrument flying, and became an experienced north Atlantic rim airline.

For one of the most thrilling stories of flying ever written, I recommend Chapter XIII of "Adventures of a Yellowbird," a chapter entitled "The Moments of Terror." Just thirty-one pages. The word "terror" is an understatement. The Convair 240 flight that Mudge chronicled became a triumph of man over adversity. Pilot Mudge has given me permission to reproduce it. See link labeled "Moments of Terror" at the very end of the links below, or way back up the left side of this page opposite the Stinson Tri-motor photo.

Part 2. Corporate Aviation

First installment of this Part 2., April 25-26, 2013

Chapter I.

On pages 5,6,7and 8 in my book, "The Triumph of Instrument Flight," (see cover, at top left of page) I introduced Russell Holderman, manager of the Leroy, New York, airport (its name was D.W. Airport after its patron and founder, Donald Woodward, who was then President of the Jello Corporation, located in Leroy, New York.). Holderman was an instructor pilot for WW I Army aviators. Holderman made his first flight in 1913. My first flight came in 1930, with Holderman as pilot of a Stinson "Detroiter."

Russell Holderman would accept a 'groundbreaking' offer from publisher Frank Gannett in 1934, to be Gannett Newspapers' Chief Pilot.

In 2012, Bill Benton of Batavia, NY, helped me contact Nancy Holderman Durante, a niece of Russell Holderman. She is the daughter of Holderman's youngest brother. Mr Benton loaned me a book on Stinson aircraft (that I hope I returned), and provided more information about the town of Leroy , NY, than I had absorbed as a young boy in the 1920s and during a visit to the Jello Museum in Leroy in 2003. Bill Benton also put another point on aviation history's curve: A Stinson Reliant aircraft! Benton had purchased the plane, which had been stored in a hangar in Ottumwa, Iowa; it had been damaged from a nose-over in a field near there. The aricraft's tail number identified it as an aircraft that had once (late 1930s) been owned by Gannett Newspapers.

Together, Bill Benton and I established contact with Dixon Gannett, son of Frank Gannett. Duirng Dixon Gannett's young life, he had often chatted with pilot Holderman while the two were on the ground waiting for Frank Gannett to return to the Gannett plane from a business visit in some city where Frank Gannett's expanding newspaper venture had taken the trio. Bill Benton was seeking knowledge about the Reliant's exact original color and markings.

From Dixon Gannett I learned that Gannett Newspapers had owned more than one aircraft at a time. Bill Benton determined that the Stinson Reliant's time with Cannett included the year1939, so that cnfirms at least one year for Gannett Newspaper's two-airplane ownership. (For an earlier presentation of Dixon Gannett's 2012 recollections on the aviation subject in his early years in his family, go to Early Aviators: Russell Holderman; news empire builder Frank Gannett. Leroy NY Airport; Donald Woodward; Ray Hylan & a Jenny; Lindbergh's Flight There is a return link there to get back here.

On April 24, 2013, Bill Benton informed me that he had sold the Stinson Reliant to four pilot-qualified brothers. They will do, or will contract, the restoration of the aircraft. I am hoping that Bill Benton will stay in touch with the brothers so I can determine when that Stinson flies again! (I am 92 so I hope they hurry.)

Meanwhile I have access to another Corporate Aviation story of modern times. My youngest son, Vincent Dailey's company, has acquired (~2011-2012) a corporate aviation company, after using that company's service extensively during my son's ompany's formative years.

Corporate Aviation is a huge business. An owner of NetJets is Warren Buffett. My company (1962-76), Scott Paper, owned two Lockheed JetStars. I made trips in them in the early 1970s. A four-jet speedster for the executives!

Frank Gannett and his Chief Pilot, Russell Holderman, may have been the originators of the business we now call Corporate Aviation in U.S. business and aviation history.

Everything I have read about Frank Gannett spells 'doer.' A skilled pilot, Holderman was also a doer. When Gannett acquired Holderman's services, Holderman was not only a distinguished aviator, he had helped design and manage a history-setting airport at Leroy, NY,, and was also a Stinson aircraft 'rep.' I learned later that Holderman's wife, Dorothy, was a top airplane salesman. Another doer!

See this page, www.daileyint.com/flying/flywar3.htm for future installments. Gannett, Holderman, Benton, Gannett again, and Durante, are names to keep in mind. I will shortly add to the list of names and places. Why add to the list? Surprisingly few summaries of Frank Gannett, and his Gannett Newspapers, include the word, 'aviation.' I will have to expand the search horizon.

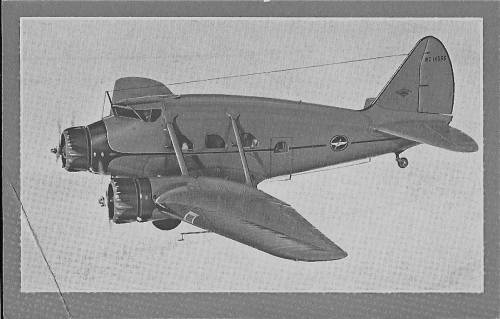

(Photo, courtesy Dixon Gannett who flew many miles with Holderman on trips in a Lodestar like this with his father, Frank Gannett.)

Above, a Lockheed Lodestar, one of many Lockeed designed-and-built twin-tailed aircraft. This is like one was piloted after World War II by early aviator, LCDR Russell Holderman USNR. This is one of several corporate aircraft over a period of years that took Frank Gannett all over the U.S., as Gannett built a national newspaper chain from five papers in New York State.

The Gannett Co. newspaper group is now topped with the national newspaper, "USA Today."

In the 1920s and 1930s, the New York Central Railroad (NYCRR) ran several crack passenger trains between New York and Chicago each day. I have personally stopped at, embarked, and/or disembarked, at the Buffalo, Rochester, Syracuse, Utica, Albany, Harmon, 125th Street and New York City Grand Cental stations in NYCRR trains. It is not farfetched to conclude that Mr. Gannett felt that aviation was a tool to expand beyond New York State.

The twin tail aricraft design served Lockheed through many prominent aircraft, including the P-38 Lightning and the Constellation (Connie). .

(Beech Aircraft offered their twin tail D-18 in several versions, one of which became an instrument training aircraft for the Navy as the SNB or JRB, in the 1940s. (I was one of those pilots in-training in the Navy's instrument flight training program.)

While the earlier trimotors (see Part I . An Early Airline. above) carried passengers, an essential plane in airline development can be credited to Lockheed and its early Electra series, which enabled the airlines and their pilots to fly passengers to their destinations despite cloud-shrouded landing fields. Pilots now had to learn to fly "instruments," and the Sperry gyro-controlled trio of artificial horizon, directional gyro indicator, and 'turn and bank' instruments on instrument panels like those in the Electra series (1930s) enabled airlines to maintain "schedules." (I was once introduced to the Gross brothers who ran Lockheed Aircraft.) The Boeing 247 was a competitor to the Electra 10s in early airline service .

Chapter II. begun April 28, 2013

I have set out here to fill a gap in history. My objective will be to highlight some contributions that publisher Frank Gannett made to the business of Corporate Aviation.

In that pursuit I had some foreknowledge but was surprised to discover that Gannett was a booster of aviation beyond his own direct interest in how aviation could help him in his business objectives as a publisher. Example: A copilot for one of Gannett Newspapers' aircraft was an aviation columnist for Gannett's Rochester Times-Union evening paper.

Gannett was able to accomplish directly, as a publisher, what Boston & Maine Airlines had to go to extraordinary lengths to accomplish in its founding years. Robert Mudge's book," Adventures of a Yellowbird," tells how the airline enlisted Amelia Earhart to be their Vice President of Operations. She would not pilot their aircraft. She would not even direct air operations. She would use her considerable pilot prestige to obtain favorable press stories. She would focus on getting ladies to fly as passengers. Then, she would urge them to then tell their husbands, "it is OK to fly."

In this discovery effort, the greatest surprise has been the lack of mention of any aspect of aviation in much of the source material available about Frank Gannett. There is Wikipedia. Their coverage borrows heavily on the one biography of Gannett, "Frank Gannett, A Biography" by S.T. Williamson, dated 1940. Wikipedia's organization of the Gannett material covers: Early Life and College Years, The Rise of Media Mogul, Rivalry with Randolph Hearst, Founding of a Corporation, Part in Politics, Later Years, and Legacy.

Gannett was born in 1876 and died in 1957. He did not marry until March 1920, just one month before my Mother and Father, who were a generation younger. I was born in Feb. 1921 and my parents had moved back from Rochester, NY, to Brockport, a small village 19 miles west of Rochester, where my Dad had grown up. One of my first recollections is reading the Rochester Democrat & Chronicle, one of the New York State daily papers that Gannett and two partners owned. That paper was a morning daily and published Sundays. I was already helping a town buddy, Pete Scripture, deliver the evening Rochester Times-Union, another in the Gannett group, but for reading papers ,the 'Sundays' were 'where it was at.' Hearst's Rochester Journal-American, and the D&C as it had become known, battled furiously. Hearst picked up readers with a torrid series on the 'munitions makers.' DuPont was condemned by Hearst as one of the guiltiest of all munitions makers. Hearst showed photo after photo of dead bodies and dying people. All this even as DuPont had been one of the munitions manufacturers which helped the U.S. come out on the winning side of World War I. The Democrat & Chronicle stayed clear of this effort to attract readers, countering with better local coverage including my interest in sports. Hearst took a couple of beatings from the Gannett group in the State, and departed Rochester, I am guessing about 1930 or 1931.

I had had my first flight with Russell Holderman at Leroy, NY in 1929. There were some root reasons for me to be interested in Gannett, and in aviation.

Frank Gannett passed on Dec. 3, 1957. As chance would have it, I was living back in Rochester NY at that time. I have discovered a collage of photos and articles, headed "History and Highlights of the Life of Publisher Frank Gannett," in a web search I made on April 28, 2013. I will come back to a page in the "Potsdam courier-freeman" newspaper in a later chapter. But here now, the Niagara Falls Gazette.

Chapter III

Frank Gannett. Early Life. (Prepared May 3, 2013, with appreciation for the Niagara Falls Gazette of Dec. 3, 1957.)

(Disclosure: While living in Brockport, New York, 19 miles west of Rochester, I assisted in daily delivery of the Rochester Times-Union about 1930, and was a quiz contestant on radio station WHEC in Rochester about 1931. My photo appeared on the front page of the Niagara Falls Gazette in 1935. My sons Franklyn III and Michael delivered Gannett papers in the Park Ave. section of Rochester NY, 1957-59.)

Before getting further into my observation that Mr. Gannett's credits have rarely mentioned aviation, I will list here just a few subheads (*) and early highlights in Gannett's business life as these appeared in the Niagara Falls Gazette's edition of December 3, 1957. The Gazette was a Gannett paper. Frank Gannett was born in 1876.

*Began Career as a Reporter *Started in Syracuse *Purchased Ithaca Journal in 1912 "Merged two Rochester NY papers into the Rochester Times Union in 1918"

The Gazette's Gannett acquisition history list, by city, then resumes in sentences with dates: Utica 1921, Elmira 1923, bought out two associates 1924, Newburgh and then Olean in 1925, Hartford (CT) Times, two Albany papers, Rochester Democrat & Chronicle in1928, then Ogdensburg. He was not finished acquiring papers along the northern tier of New York State but paused there, and then came a telling acquisition. It was the Danville IL Courier-News, acquired in 1934. He then resumed later that year back in New York State, with acquisitions at Saratoga Springs, Massena and Ogdensburg.

(The forgoing sentences are just a small excerpt from the Gazette's article in 1957. I have taken some liberties with sentence structure to create the paragraph above.)

As concentrated as the foregoing activity seems, it was just the beginning. Frank Gannett would add TV and radio stations beginning in the 1950s. The reader can go to the web for the later acquisitions, and the birth and success of a national newspaper (USA Today) that comprise the huge Gannett Co. holdings of 2013. The properties reach over 10 million readers and viewers.

For this review, I should mark a significant date in March 1920, when Frank Gannett was married to a Rochester girl, Caroline Werner. (My own parents were married in April 1920.)

Gannett, in his postgraduate study period at Cornell, was selected by Cornell's President to act as the latter's secretary, as the two were sent in 1899 by the U.S. government to the Philippines to report on the change of sovereignty over those extensive islands when Admiral Dewey and his flagship Olympia, and a U.S. fleet supporting U.S. ground forces, conquered the Spanish defenders' Navy and ground forces there. That was the War of 1898 aka the Spanish-American War. The Niagara Falls Gazette in its reporting on Frank Gannett's death in December 1957 noted that Gannett learned early and at first hand of the expanse of the Pacific Ocean, and the world players in that part of the world. He would visit Europe extensively, fly to South America, and return to the Pacific. Like an acquisition in Danville, IL, those travels propel our story out of New York State and into the aviation aspect I intend to pursue..

"Expanse," like the Philippines in 1899. "Expansion," with acquisitions to create a New York State news chain, 1910-1930. Marriage in 1920. Newspaper acquisition in Danville IL in 1934. He began as a reporter, was a skilled writer, and had vision that few possess. He also made seemingly quick decisions; the record supports a man who was able to rapidly acquire and make use of hard data.

This brief examination of Frank Gannett's life may be the clue to answer why aviation is mentioned so little in recounts of his life........... Just no space to squeeze it all in!

I am going to try to offer enough to suggest that Frank Gannett seized on the opportunity for a businessman to fly, as a tool in the creation of a national chain of information properties. One can just wonder if he realized, that in using air transportation as a tool, he was a primary factor in creating yet another business! Remember, New York State, then Russell Holderman (1930) and Gannett's first airplane, 1934? But surely by Danville, Illinois in 1934. I'm betting Stinson Detroiter in 1934. After all, Holderman was also Eddie Stinson's salesman!

Accepting any and all improvements, comments, and corrections. (See "Contact Author" at the beginning of every page.

Chapter IV.

May 5, 2013.

Nancy Holderman Durante is a niece of Russell Holderman. Her book, "Between Kittyhawk and the Moon" informs us, in Russ Holderman's own words, that he became Chief Pilot for Gannett Newspapers in 1934. I'll be referring to that book, and also to "Wings Over LeRoy" by Brian Duddy, and Paul Moxin's "One Foot on the Ground," to see if we can discover key developments in the Holderman-Gannett relationship, especially dates of those developments.

Here is a passage from the Dedication in Nancy Durante's book that compiled Russell Holderman's writings.. This would take place before 1929.

"In the early days of aviation, Russ would try to interest people in an airplane ride. He would take a plane out to a field on Long Island (somewhere near where Roosevelt Field is today) and his wife Dot, would sell hot dogs. No one was interested in a ride. But planted in the crowd was his young brother, who was just waiting for a ride. So Russ would say to the crowd 'who wants to go for a ride?' When no one responded, he would say 'how about you sonny?' The two would take off for a short spin over th field. After they landed, and the young brother (my Dad) was so happy. Russ would then say to the crowd, 'OK folks, now who else would like to go for a ride?' And then he would finally get someone to take a ride. And so Russ was able to share his enthusiasm and love of flying."

That paragraph of Nancy Durante's is almost exactly how I met Russell Holderman. Except it was now 1929 (but later info dates it as 1930), he had someone to sell tickets and take in the money, while he, now an airport manager (DW Airport in Leroy NY) just did the flying. That introduced me to my first flight. It was with Russell Holderman piloting a Stinson Detroiter for about half an hour over western New York State. My Dad, Mom and Sis were aboard. I could see Niagara Falls! I was eight years old. Russell Holderman, gifted pilot and enthusiastic salesman for aviation, and I, would meet just once again.

The three books referenced a paragraph or two above, were all published between 1998 and 2009, Moxin's in 1998, then the Duddy book in 2008, and Nancy Durante's book in 2009. None are narratives on Corporate Aviation. I'll be looking to see if that subject comes up at all as we move along.

Nancy Durante's book is her compilation of Russell Holderman's own writings, beginning with his first flight in 1913. Brian Duddy's book is about Leroy, New York, and the D.W. (Donald Woodward) Airport there. Duddy's book is rich in photos. Paul Moxin's book has a Rochester airport base. That is where LCDR Russell Holderman would have originated a Gannett aircraft flight as Chief Pilot for Gannett Newspapers. Although the airport opened at Leroy, New York, in 1928, was, for those times, a sophisticated operation in terms of airfield design, hangars, tower, and support, it was going to become an historical curiosity. Rochester's airport facility developed later, but had a city and a city's population to move it forward aviation-wise, until airlines and air freight created 'traffic,' the mother's milk of aviation.

So, for a few installments, this will be discovery for me as well as for my website readers. The airlines were reasonably well established by the early thirties when the relationship of Gannett and Holderman began in a serious business mode. Airline executives often went aloft in aircraft that were 'corporate,' that is, were not in the airline's passenger service, but purely a convenience for the airline executive and his or her important client. Robert Mudge is author of "Adventures of a Yellowbird," the story of the growth of Northeast Airlines, that originated as Boston and Maine Airways, to be eventually bought by Delta. Mudge told me in an e-mail that before he became a pilot in the left seat of a Northeast plane, he piloted executives of his airline, and the businessmen they did business with, in a company Stinson Reliant that was dedicated to business trips for senior personnel of the airline. For my thesis here, that 'air traffic' does not count for the business we now (2013) know as Corporate Aviation.

Prose is sometimes tiring. So, now three photos, courtesy of Batavia NY resident Bill Benton, for one (much later) period the owner of the Stinson Reliant in Gannett Newspaper's 'fleet.' The Reliant could have been the 'single engine plane' owned by Gannett about 1939. We shall see.

Ah! A misadventure on an Iowa farm field. I mentioned the upside down Reliant to Gerry Thuotte, a friend who runs the Port Townsend Air Museum in Washington State. They do aircraft restorations as one support of the museum. He immediately responded, "Yep. The Reliants were noseheavy." So, dear pilot, wherever you are, take some comforrt. We know there were no injuries. And this is surely a nice istrument panel.

Doesen't look quite so bad when she was righted and in a hangar.

Bill Benton of Batavia, New York, bought this aircraft, took these pictures, and promises to stay in touch and give us a photo when this Stinson flies again.

Chapter V. (Installment entered May 18, 2013)

Early airports, like the one at Leroy NY or one at nearby Rochester NY, were the 1920s-1930s nurturing ground for careers. I will cite just some of the careers that began on small airport landing fields in those days.

Most prominent were pilot careers with airlines. Let me thank Bruce Sorensen, a retired pilot and web friend of mine who is retired from Braniff/Northwest. Braniff is a key to one of those airline careers that was incubated at a small airport. I will be offering the example of a Rochester pilot who went on to prominence with Braniff.

But first, if piloting for a regular paycheck and long periods away from home was not to be the choice, you might start a local flying school, or, decide on aviation maintenance support, like engine and/or airframes, and fueling and even provisioning. These vocations meant you were motivated to get the hang of the many aspects of keeping an aircraft in the air. And with competence in these respects, men (and some women too) became Fixed Base Operators, FBOs in the parlance In addition to 'visit and depart' business these operators also supported pilot needs of locals who had the money to own and fly private aircraft. (A reader who is interested in how technology change can impact a city could go to Amazon.com and purchase, for $2.99, my e-book titled "The Rochester I Knew." That story is not about aviation.)

Let me note that Corporate Aviation, my principal subject here, depended on FBOs, but eventually also placed maintenance and replacement business with larger regional operators, even those in another country. Of all of these business opportunities, Corporate Aviation was last to appear in a recognized business sense.

One downside was the future for career opportunities that were first to appear in the early 1930s in a smaller town like Leroy, New York. Those opportunities were not going to survive there. The opportunities moved on and people moved with them.

A city of some size not only meant more potential flying-need customers, but also meant that the whole burden of growth could rest on multiple legs. Cross support was essential. A flying school was not likely to do its own maintenance and survive, at least in its critical early years. Let me just provide one example of the opportunity that a medium sized city's early airport provided to one pilot.

We are in the early 1930s.

On page 10 of Paul Roxin's book, "One Foot on the Ground," (pilots put a small pan of sand in their planes so the fearful passenger could have 'one foot on the ground') there is a sentence that begins, "Pete Barton of Rochester Aeronautical Corp. invited George Cheatham to fly Pete's Fairchild 24." Cheatham accepted, and a few lines later one discovers that the flight of the Fairchild 24 ends when the Fairchild lost its prop and crankshaft, and Cheatham made a dead stick landing on the Rochester Airport's runway; he and his passenger had to push the plane off the runway. Then, another paragraph of Roxin's book begins, "In 1938 George went to work for Braniff Airlines and eventually became its'......" More coming.

After an inquiry to him about George Cheatham, I received from Bruce Sorensen, retired Braniff/Northwest Airlines pilot, and e-mail friend, the following paragraph:

"George Cheetham certainly does ring a bell. I never flew with him but would see him in operations at DAL. A courteous hello was about it. He and a couple other fellows were legendary at Braniff.

"1911 - 1987 Braniff: Early Overall Seniority; Braniff 1 Hire Date: 4/28/1938 Last Crew Base: DAL; Flown West 8/3/1987 Age at Death: 76; Type Ratings: B-707 B-720 BA-111 CV-240 CV-340 CV-440 CW-46 DC-3; "Additional Type Ratings: DC-4 DC-6 DC-7 L-49 L-188.

"1st Former Employer Automobile Racing; 2nd Former Employer Flew in Air Shows; 3rd Former Employer Braniff 1 1938-1971; 4th Former Employer Gannett Newspapers Pilot

"George Cheetham, a native of Rochester, NY turned down a scholarship to Syracuse University to take a job cleaning airplanes so he could pay for flying lessons. At age 19, he was one of the youngest people to earn a transport license from the Civil Aeronautics Authority. He gained recognition during the 1930s as an aerobatic pilot and then was a corporate pilot for Gannett Newspapers."

Frank Dailey side-comment: When consulting many sources there are bound to be little questions like the spelling of George Cheetham's last name. My own name changed from baptismal certificate, to birth certificate, to social security card. I began as Francis, migrated to Franklin, then to Franklyn.

I have no certain explanation for Cheatham vs. Cheetham. George could understandably have been known to Rochester writer Paul Roxin, as George Cheatham, but then George went on a payroll at Braniff and decided to make sure that company used the spelling on his birth certificate, maybe to keep the new Social Security folks happy. Social Security began in 1935 so that would be my best guess.

Let me summarize what I'd like to emphasize in the Braniff credits for George Cheetham. He became a Braniff pilot in 1938 and moved to Dallas in 1942, when the company's headquarters moved to the city. He served as Braniff's chief pilot, director of flight, and director of flight operations and training before returning to a job as a pilot in 1965. Cheetham retired from Braniff in 1971 after logging more than 6 million miles of flying and piloting aircraft that spanned much of the early history of aviation. He flew Military Airlift Command charters into Southeast Asia during the Vietnam War and once flew Lyndon B. Johnson, who was vice president at the time, to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil to sign a treaty.

George was a member of the OX5 Club. To aviators, this is like a lady being a member of the DAR, Daughters of the American Revolution.

Back now to the subject of Corporate Aviation.

The relationship between Frank Gannett and Russell Holderman is the backbone of my story here. We know that the formal relationship of the two began in 1934 when publisher Frank Gannett hired pilot Russell Holderman to be his Gannett Newspapers pilot. I'd be pretty certain the two knew each other before 1934, with the record Holderman was building at the Leroy, New York airport that opened in 1928.

That sea trip to the Philippines in 1899, the Wright Brothers feat of 1903, Lindbergh's transatlantic crossing to Paris in 1927 and the inauguration of Clipper service to South Armerica in 1931 are just a few of the mobility events that would have stimulated Frank Gannett's busy mind.

From an article that appeared in one of his papers, we find Gannett, the publisher, going back to his news writer days while enrolled at Cornell. Ever the traveler, Gannett chronicles an air trip to South America in one of Juan Trippe's Brazilian Clippers. This could have been 1932 as that service was inaugurated in 1931.

In the newspaper clip sent to me by Frank Gannett's son Dixon Gannett, a photo accompanies Frank Gannett's article. It shows a crew of the "Brazilian Clipper" standing in front of their aircraft. The aircraft is a flying boat, a Sikorsky of the S-class, likely an S-38 or S-40. Those were the flying boats that soon after began service across the Pacific. The crew of the Brazilian Clipper numbers seven. One man is identified as an Apprentice Pilot. On the job training, OJT, was and is still an airline practice.

The Clipper crew are trim looking men, with an experience look to them. They appear in dark uniforms. Six wear white caps, with some gold on most of the cap visors. From L-R they are identified as "Apprentice Pilot H.G. Gulbranson, Pilot W.G. Culberson, Captain Edwin Musick, Flight Mechanic C. W. Wright (you could access any one of the four engines through a wing), Radio Operator Z.A. Wenkstern, Purser R. W. Kerr, and Steward Paul Schneeburger." The last named is in white shirt, short white steward jacket, and wears no cap. These men are all trim and tall, very evenly matched in height.

This Clipper crew are standing in front of their Clipper, which is behind them on a dock, on beaching gear. These are strictly seaplanes so special beaching gear had been designed to pull them up on dry land.