U.S. Navy P2Y-1 seaplanes units reach forward from Washington State to Sitka, Alaska. First crews reach Kodiak and Dutch Harbor in the Aleutians.

U.S Navy's northwest air buildup had begun. After U.S. troops retook Attu and Kiska inWorld War II, Navy air at NAS Attu became part of the counterattack against Japan.

Update here to 1946 and FAW-4. Photos of P2Y-1s, P2Y-2. Original mainland base at NAS Sand Point Seattle WA gradually replaced by NAS Whidbey Island Washington. The Navy's early decision to move air units northward from continental U.S.to the Alaskan Peninsula and the Aleutian Chain of islands became a major factor in World War II. The U.S. Army too, moved into continental Alaska and then its U.S. Army Air Corps also established bases westwward with names like Ft. Randall and Ft. Glenn.

For closely related material, go down the left column to:

Aleutians Anti-Submarine Warfare

or just hit these links. These are all about Alaska and the Aleutians, and contain both U.S. Army and U.S. Navy stories.

Copyright 2013 Franklyn E. Dailey Jr.

- Barnstomers and Early Aviators

- Budget Flying Clubs

- Aviation Records

- VFR to IFR

- Early Airline Development

- Flight Across the Atlantic

- P-40s to Iceland

- Alaska Based Navy P2Y-1's

- Buckner Goes to Alaska

- Ship-to-Ship Battle

- Naval Flight Training

- NAS Instrument Training

- Aleutians Anti-Submarine Warfare

- Search & Rescue

- Gyros and Flight Computers

- Baseball Team Lost in Flight

- Tomcats and Boeing 777s

Context: Instrument Flight, vs.Flight

Contact Author Franklyn E.Dailey Jr.

The demanding conditions of Alaskan weather for any form of human movement have proved a challenge for flight over its spectacular but often forbidding land and sea areas. My own introduction to all-weather instrument flying ,as an every day duty, came in the Aleutian chain of islands. Though Alaska seemed challenging, and would live up to its dangerous reputation during my tour of duty, others who had preceded me had left lessons behind that would help me survive. After completion of my final operational air training in Navy PB4Y-2 Privateer aircraft at NAS Whiting Field near Pensacola, FL, I was a qualified copilot ,ordered to San Diego, CA.

At San Diego, I was re-directed to Seattle, thence to NAS Sand Point on Lake Washington, for further transportation to NAS Whidbey Island, to join Navy PB4Y-2 squadron, VP-107. It was now about June 1, 1946. I bunked overnite at a Sand Point BOQ that featured two lovely grand pianos in its spatious foyer. Never before or since did I overnite at a Bachelor Officer Quarters so well appointed. NAS Sand Point could accommodate both land and seaplanes. Its span of active service was 1921-1970. I would discover as I made the trip to Ault Field at NAS Whidbey Island, in a small Navy utility plane the next day, that Whidbey was replacing Sand Point for operational units. NAS Whidbey was itself undergoing change, as its seaplane facility was being closed. The operational air Navy was leaving its its seaplanes behind for an amphibious aircraft, namely the Convair PBY-5A Catalina.

1946-48, NAS Whidbey Island WA, U.S. Navy Air Base for Fleet Air Wing Four. (more later on this page)

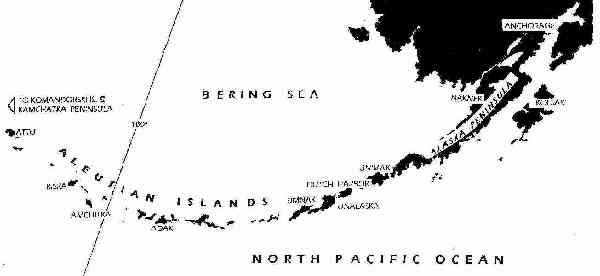

In 1946, NAS Whidbey was rear base support for three PB4Y-2 Privateer, each nine-plane squadrons, VP-107, VP-110, and VP-120. There were two PBY-5A Catalina squadrons, VP-53 and VP-62. The Privateer squadrons were forward based at NAS Kodiak. and the Catalinas were forward based at NAS Adak. The PBY-5As could also stop in at NAS Dutch Harbor, restricted there mostly to water landings. And all of the foregoing aircraft routinely stopped in at NAS Attu, a landplane facility. U.S. Army Air Corp. bases at Ft. Glenn on Umnak I. and at Ft. Randall at Cold Bay on Unimak I. were places with good runways, to land and get service when necessary. The latter base supported the Army's 10th Rescue Squadron which flew OA-10 aircraft, the Army designation for the PBY-5A. Navy patrol aircraft also landed at Elmendorf Field at Anchorage and at Ladd Field at Fairbanks, Alaska. Elemendorf was frequently our 'alternate' on instrument flights returning up the Aleutian Chain or coming up from NAS Whidbey. Shemya,at the end of the island chain had a good airfield, a GCA unit , and strenth five Bartw lights for night landings. That field was the preferred 'alternate' for flights westbound out the chain.

My CO, LCdr Ed Hogan, and I as his co-pilot third tour in 1948, also landed our PB4Y-2 at Big Delta, an outlying field for Ladd Field at Fairbanks, in order to survey that unused (1948) field as a temporary base for the Navy photo squadron, VPP-1, assigned to survey Alaska for the U.S. government. To filll out this base untilization summary in one very important aspect, after the recovery of Kiska and Attu islands from the Japanese, NAS Attu was perhaps the busiest base of all for the remaining war years, supporting PV-1 and PV-2 bombing raids on the Kuriles. Fleet Air Wing Four which was the Navy operational command for all of these flight operations. That command had been based in the Aleutians in the war years but but by the time I arrived at NAS Whidbey in June 1946, the air wing was based at NAS Whidbey Island.

Going back in time, briefly , beginning in the 1930s, home base operations for 1930s Navy patrol aircraft in Alaska were at NAS Sand Point, Washington.

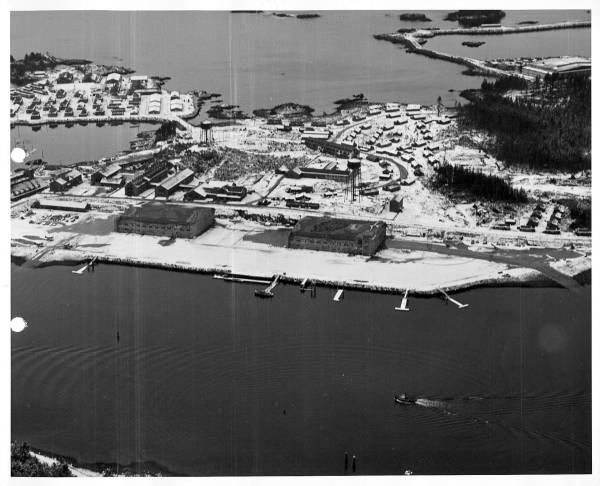

Based on 1938 war plans, by 1941 the U.S. Navy had established three Alaskan bases. Nearest to the continental U.S. was a seaplane base at Sitka, Alaska, on the northeast coast of the Gulf of Alaska. West and a bit south of the base at Sitka, across the Gulf of Alaska, an airbase at NAS Kodiak, Alaska went into commission on June 15, 1941 along with a submarine anchorage right next door. Kodiak is an island off the south side of the Alaska Peninsula.

Illustration 7 -The North Pacific (from the book at uppper left)

Further west, the U.S. Navy put a seaplane base in operation at Dutch Harbor on Unalaska Island just west of the end of the Alaska Peninsula. This base also accommodated submarines. Prewar, Dutch Harbor marked our only active naval base in the Aleutian chain of islands. Lee B. Di Napoli provides an intimate glimpse into the establishment of the U.S. Navy's early Alaskan bases.(excerpted from the book)

Lee Di Napoli, along with his friend Roy A. Evans, reported to seaplane squadron VP-16 from the USS Langley in November, 1938. At the time, both men were Seaman 2/c. (The Langley was the U.S. Navy's first aircraft carrier.) VP-16 and a number of other seaplane patrol squadrons, then based at the Naval Air Station (NAS) Sand Point, in Seattle, Washington were shortly re-designated numerically into the VP-40 series. VP-16, one of the five patrol squadrons at Sand Point, became VP-41, flying PBY-3 aircraft. Two of the patrol squadrons flew PBY-3s, and the other three flew the predecessor aircraft, P2Y-2s. Two ships that were docked at Sand Point at that time served as seaplane tenders, the USS Williamson a converted World War I four stack destroyer, and the USS Teal, a seagoing tug. These ships were assigned as tenders for the five aircraft squadrons. A seaplane tender fills some of the functions for seaplanes that an airbase does for land-based planes.

The squadrons deployed to Sitka, Alaska, on a rotating basis, for three-month tours. From Sitka, during its three-month tour, each squadron would deploy at least one time to Kodiak, Alaska and to Dutch Harbor, Alaska. One of the Sand Point seaplane tenders would have been sent forward so that it would be in place at each of those stations when the aircraft squadron deployed so that squadron personnel could be housed aboard the tender. The squadron aircraft would moor to buoys. The buoys had been placed at Kodiak and at Dutch Harbor in the mid-thirties. No ramps were available to beach the aircraft. There were no Navy land plane fields in Alaska in those early days. All Navy aircraft activity was sea-based.

Illustration 8 (from the book) -A Formation of Navy P2Y-1's (from the book, but see next Note)

(Note: In my book on instrument flying, pictured at the start of this page, I identified the aircraft in the photo above as P2Y-2 aircraft. A reader, "Old Jack" Reich, informed me by e-mail that these were P2Y-1s. Jack had been involved with the Naval Aircraft Factory and with Convair in the changeover to the P2Y-2 model. One change was to 'fair' the engines into the wings. I was a fresh caught Midshipman at the U.S. Naval Academy in 1939 when I snapped the next photo. As Old Jack noted, and I had failed to note, the later model's engines were indeed faired into the wings.)

FED-1. A Navy P2Y-2 pictured on a dock at the U.S. Naval Academy in 1939

On paper, each patrol aircraft based at NAS Sand Point had twelve planes, but, due to budget constraints, only six aircraft were assigned to each squadron. Each squadron usually had eight commissioned officer pilots assigned. Six enlisted pilots and a dozen aviation cadets filled out the pilot complement. Since the seaplane tenders were usually short of their prescribed enlisted complement, junior radiomen in the aircraft squadron would be assigned temporary additional duty (TDY) to supplement the tender personnel in manning the duty radio circuits. Lee Di Napoli, who had become a radioman striker, made trips to the three squadron deployment stations in Alaska on both the Williamson and the Teal.

The pace of activity quickened in the spring of 1939. Materials for six prefab buildings were loaded aboard the Williamson at Sand Point destined for Kodiak. Lee Di Napoli, now a radioman third class (RM 3/c - a rated petty officer), made that trip to Kodiak on the Williamson. He helped assemble the 20-foot by 20-foot buildings along the beach of Women's Bay at Kodiak. These buildings were intended to house crews that would come later to begin constructing NAS Kodiak's support buildings and later, a landing field. The advance construction force from the Williamson found many prospector claims in old tobacco tins nailed to posts along the beach. The sailors simply pulled the posts from the ground and threw them into the bay. It is not known if the prospectors ever sought remuneration from their government.

A four-man crew left Sand Point, Washington, in the summer of 1940 in a cabin cruiser proceeding to Sitka, Alaska, via the Inland Passage. Di Napoli, now a RM 2/c was part of that crew. The boat was put into service in Sitka's harbor to send radio signals to seaplanes trying to get back into Sitka during bad weather. Many times Lee DiNapoli went out in the boat to put his now practiced radio finger on the transmitter key to create radio signals for a returning PBY-3 or a P2Y-2. The aircraft would take radio direction finder (RDF) bearings on Di Napoli's radio signals, get down under the overcast and land in the ocean offshore, then taxi into the harbor. There were no fixed radio installations at sea. Landing in a sea area where you had visual contact with the water, and then taxiing in to a fogged-in harbor base, was a recognized operating procedure. That base might have had a very low ceiling, too low to attempt to land in, but usually would have visual taxiing airspace on the surface under the low ceiling.

By the spring of 1941, Di Napoli, now a RM 1/c, became first radioman of aircraft number 41P2, piloted by Lt. Paul Ramsey, who would later become Commander in Chief Pacific (CINCPAC). The crew chief was Ed Froelich, an Aviation Chief Machinist Mate (ACMM). Co-pilots rotated from crew to crew. On one deployment to Sitka, this aircraft made stops in Kodiak and Dutch Harbor. Construction was now well advanced at Kodiak, with a dock now in place for the tenders and a ramp for the seaplanes. (The seaplanes could be joined to special beaching wheel-sets, then pulled up the ramp for maintenance on dry land.) During that deployment, the aircraft crew could see that activity had also become more intense at Dutch Harbor. Though seaplanes still moored to buoys there, it was clear that the Navy planned for increased activity. These trips, Sitka, to Kodiak, to Dutch Harbor, back to Kodiak and then back to Sitka took about two weeks.

The friendship between Roy Evans and Lee Di Napoli lived on long after their early days on the USS Langley. Both left VP-41 in May of 1941. Roy went to flight school and Lee went to a seaplane tender at Portsmouth, Virginia. At the completion of flight school, Roy and his new bride Lois visited Lee Di Napoli's parents in New York. The date was December 7, 1941! But, that date gets ahead of our story here.

Let me now introduce two 1941 pilots from the U.S. Navy's Sitka operations who likely overlapped DiNapoli and Evans in the Sand Point /Sitka air operations. These two would later serve out of Dutch Harbor as command pilots of PBYs when the Japanese attacked and won Attu and Kiska. Their names are Bill Theis and Jack Litsey.

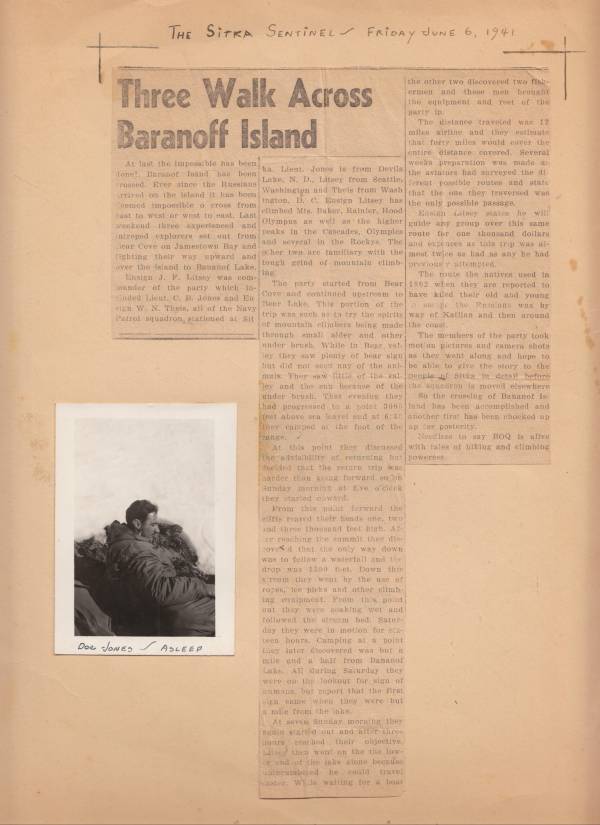

This next part of their story is not war, or even flying, but the story of a land crossing of Baranof Island. These pilots were still working out of Sitka, the advanced station for seaplane operations the Navy projected from NAS Sand Point, Seatttle Washington.. Pearl Harbor and Midway and and the fierce effort to resist the Japanese at Attu and Kiska and the effort to regain Attu and Kiska had were still in the future, but not too far in the future.

Still, Sitka must have had its boring days.

Bill Theis will be our arrator.

Theis' story is set on Baranof Island. Here is what Wikipedia summarizes about Baranof Island.

"The island has a land area of 1,607 square miles (4,162 square kilometers),[3] which is slightly smaller than the State of Delaware. It measures 105 miles (169 kilometers)[3] by 30 miles (48 kilometers) at its longest point and perpendicular widest point, respectively. It has a shoreline of 617 miles.[4] Baranof Island hosts the highest mountain in the Alexander Archipelago, and is the eighth largest island in Alaska, the tenth largest island in the United States, and the 137th largest island in the world. Its center is near

57.000°N 135.000°W. Most of the island lies within the limits of Tongass National Forest. A large part has been officially designated as the South Baranof Wilderness."

Now, Bill Theis' Baranof Island transit (human legs) story: (What follows in quotes is a transcript that was provided to me by Bruce Sorensen, retired Braniff/Northwest pilot, whose father flew Navy Lockheed PV-1 bombing mssions to Paramashiro, out of NAS Attu when that island was retaken from the Japanese.)

"Crossing the Island (Baranof) had never succeeded. Many parties had tried and either (were) never heard from again or gave up altogether.

"We assembled a party of 4. One was my co-pilot, (Jack) an experienced mountain climber.

"The plan was to give us 3 days then be picked up by a PBY on Baranof Lake.

"The 4 of us started a trek through the marshy tundra and underbrush.One of the party gave up and returned to a waiting boat. As he was leaving, he said "I will never see you guys again"

"In the photo, where there is something that looks like a horse's head, there is a pinnacle.

"The mass of tangled ice beneath the pinnacle is where we spent the first night on a ledge,

"We huddled together.

"The next day we got to the top of the saddle where the glacier started towards the East.

"Jack got all of us tied together with his being in the middle. He cautioned - "Never leave the perpendicular to lean backwards".

"Half way down, I leaned backwards, lost my footing and started skidding down the glacier. My backpack with all the food supplies and the only rifle, rolled away.

"Jack was able to stop the fall and we started off again to get to the bottom where there was a glacier-fed stream.

"We first tried hiking in the stream but immediately became cold, wet and hypothermic.

"We then took to the underbrush. Suddenly the sun disappeared, The sky was black with deer flys and monstrous mosquitos. Our arms ans legs were swollen to twice their normal size from being bittened, and hits from Devils Claws thorns.Reaching a meadow we came upon a Grizzly and her cubs. No trees to climb and no rifle. We just waited until she sauntered off.

"Five days had now passed with nothing to eat except berries. We had been alternating between the stream and the brush. On the 7th day, Doc Jones (one of the party) and I lay down to die. Jack took off for the lake and ran into the PBY search party which found Doc and me. Stretchers and a week in a hospital ends the story/"

"I forgot to add this little tidbit to the story.

"On the ledge where we spent the first night, when I woke up, I heard Jack chiseling on the rocks. He woke us up and showed us a hunk of rock with what looked like gold. He packed it up and much later had it assayed. Turned out to be 24 carat. He spread the word around that for $10,000, he would take a party to the site where he found it.

"There were never any takers."

Bill (Theis)

'Jack' introduced in the beginning of the story is Jack Litsey. Litsey (Ted) Young is a son-in-law of Jack Litsey. Ted provides the original of the transcript that Bruce Sorensed provided to me, Frank Dailey Jr.That 'original,' pictured below ,supplies some essential information. Here is the .jpg of the article that Ted Young forwarded to me.

TY-1. The Sitka Sentinel Friday June 6, 1941 "The Walk Across Baranof Island." Inset photo is of Doc Jones, third member of party.

For photo credits, TY is for Ted Young, son-in-law of Jack Litsey, who became CO of VP-120 at NAS Whidbey Island, Washington, during my 1946-48 service there. MB is for Malcolm Barker, who was serving as a pilot-navigator in VP-120 when I arrived at Whidbey Island for service in VP-107 in June 1946.

Bruce Swenson adds a 'tidbit' to the Sitka Sentinel story (see reproduction above) of the 1941 crossing of Baranof Island. This next e-mail was sent to Bruce by Bill Thies one of the three men in the Baranof Island crossing party.

From: BillT (Ed. Note: Bill T. is Bill Thies)

To: Bruce Sorensen

Sent: Thursday, May 30, 2013 7:13 PM

Subject: Sequel to crossing Baranof Island

Bruce,

I forgot to add this little tidbit to the story. (Ed. Note: The 'story' Bill T. is referring to is the Sitka Sentinel story reproduced above.)

On the ledge where we spent the first night, when I wokeup I heard Jack

chiselling on the rocks. He woke us up and showed us a hunk of rock with

what looked like gold. He packed it up and much later had it assayed.

Turned out to be 24 carat.

He spread the word around that for $10,000, he would take a party to the site

where he found it.

There were never any takers.

Bill

(Ed. Very Sad Note: Bruce Swenson, retired Braniff/Northwest pilot and personal friend, has informed me that Bill Thies' daughter informed him {Bruce} that Bill had passed Wednesday morning, August 21, 2013. One of our courageous, skilled and intuitively observant Naval Aviators of World War II has gone. This represents a rupture in our nation's connection with events of untold importance in the war to turn back Japan 1941-45. Just as his birth family realizes so personally, our nation family has experienced irretrievable loss.)

From the dateline of June 6, 1941, on the Sitka Sentinel article on the crossing of Baranof Island, our nation would be at war in just 7 months and one day! Sitka would melt into operational history but, oh, what a contribution was made from there!

TY-2.Undated Photo of the U.S. Navy's airbase at Sitka, Alaska ~1937-1940

Go to left bottom border of photo just above, then up to the seawall. Just past the seawall, inset from the left border of the photo, see, parked on the ramp, two, side by side, single engine Navy floatplanes. These were predecessors of the SOC floatplanes that were catapaulted off U.S. cruisers and battleships in WW II war actions.

NAS Sand Point, Seattle Washington, supported the U.S. Navy's advanced base at Sitka, Alaska.The Sitka flyers set up bases at Kodiak, and Dutch Harbor. After the Japanese took Attu and Kiska, the Navy settled on Adak for its next base, and prepared a landing field at Amchitka for readying an effort to retake Attu and Kiska. Attu and Kiska were then retaken by the U.S. Army with help from the Navy and its air arm, and the U.S. Army Air Corps. Once retaken, Attu became a principal Navy air base to launch attacks on the Japanese island of Paramashiro. We take just a quick look at the 'end point.'

Lockheed, pesevered in its twin tail designs.

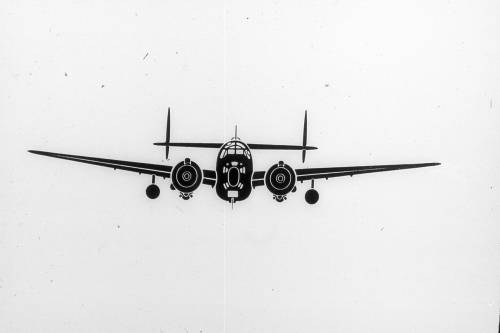

Above and below, the Navy's famed PV-1 Ventura. Flown by Fleet Air Wing FOUR pilots out of Attu, loaded with bombs and gas for a round trip to Paramashiro. All were overloaded and many never made it back and were lost. Others crash-landed on the Kamchatka Peninsula and were interned by the Soviets. (the latter did not enter the war against Japan until it was clear that Japan was doomed)

The PV-1 Ventura head on, above. Both Ventura photos above from the U.S. Navy Slide Recognition Set for World War II.

On ramp at Attu, with PV-1s in background, a VP-131 navigator brings charts for pilot Bob Feiten's aircraft to his plane.

(photo above is from the files of Bruce Sorensen, retired Braniff/Northwest pilot and friend of Bob Feiten. Sorensen's father was a PV-1 pilot in the Aleutian air campagn against Japan)

. More of Lockheed''s WW II role can be reached from the folder, www.daileyint.com/wwii/index.htm

The war has now been over for eight months. Meanwhile the home base for Navy air in the region was moved from NAS Sand Point to NAS Whidbey Island, Washington.

NAS Whidbey Island, Ault Field Operations, 1946

Next , a series of photos taken by Malcolm Barker ("MB-1" etc.) when he was a pilot assigned to VP-120 in 1946. First let me introduce Malcolm Barker.

Malcolm Barker arrived at NAS Whidbey Island sometime early in 1946. His VP-120 PB4Y-2 Privateer squadron was on deployment to NAS Kodiak when I arrived at Whidbey in early June 1946. The squadron I reported to, VP-107, relieved VP-120 at Kodiak about 1 September 1946 on my first of three deployments to Kodiak and the Aleutian responsibilty. Those three deployments are discussed in the book pictured at the upper left; the discussion includes the fact that our mission was ECM, Electronic Countermeasures.

I did not meet Malcolm Barker while we were deployed at Whidbey. When I did meet him at NAS Fort Lauderdale on Dec. 5, 2011, each of had gathered there for the annual commemoration of the Flight of five TBMs that did not return from a flight on Dec. 5, 1945, .That episode is mentioned in a History Channel presentation of the Bermuda Triangle. I learned that Malcolm had been in the crew of a PB4Y-2 out of NAS Miami, searching for the five TBM crews. As covered in my book, I had been in a PBY-5A out of NAS Banana River, FL, on that same search. So Malcolm Barker and I shared two notable Navy experiences, and I doubt if there are any two men living today (March 2, 2013) who shared those experiences.

Malcolm Barker achieved a capbility in operations of the PB4Y-2 Privateer that most pilots missed. Malcolm became proficient in the operation nof the Fairchild K-20 aerial camera. The K-20 and the K-25 aerial cameras were the original design products of Folmer-Graflex,. That companys's cameras were marketed by Eastman Kodak sometime before I went to work for Kodak in 1936. The next sequence of photos , MB-1-MB-6, were taken by Malcolm Barker using a K-20 aerial camera aloft in a VP-120 Privateer in the vicinity of NAS Whidbey Island in 1946. (I have labeled malcolm's photos MB-1, MB-2 etc. The info he forwarded for each photo is in "quotes.")

MB-1. Ault Field at NAS Whidbey, Island WA, and a PB4Y-2 Privateer are featured in the photo above. 1946

MB-2. U.S. Navy's Ault Field appears beneath the clouds. Note PBY-5A in lower left quarter of photo climbing out after take off from Ault Field, NAS Whidbey Island, WA 1946

MB-3. West side of Whidbey Island looking north, with the U.S. Navy's Ault Field in view. 1946

MB-4. East side of Whidbey Island, WA, town of Oak Harbor ahead on left and on around bay to right is Seaplane Base. 1946

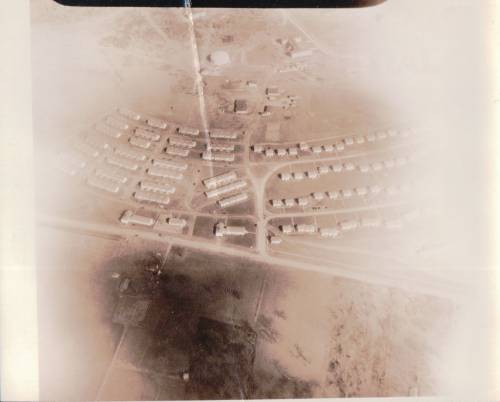

MB-5. L-R. Victory Housing up the hill from the NAS Whidbey I. Seaplane Base. 1946(seaplane base not clear)

(this website's author, wife and two sons, lived at the top of "the hill," referenced just above, 1946-48)

MB-6. Navy Privateer from VP-120 in flight near NAS Whidbey Island about 1946.

MB-7. VP-120 flight crew next to their Privateeer at Ault Field NAS Whidbey I. about 1946.

"Center Rear: The three pilots; Lt (jg) Donald W. Barker USN, PPC of this VP-120 crew. On his right, is Ens. Malcolm E. Barker (major 2013 contributor to this page, not related to the PPC) and on PPC Donald Barker's left is Ens. Haldean E. Frances USNR.

Center Front: Plane Captain Gillis, CPO USN. On Gillis' right is Landry RM1/c USN. Unnamed men are victims of memory loss, but just as important to the functioning of this Privateer air crew."

MB-8. Fairchild K-20, the workhorse camera for Navy flight crews mid-20th century. This camera evolved from the Folmer-Graflex professional camera line, marketed by Eastman Kodak in the 1930s. (the author knows; he was a billing clerk for K-20s and K-25s at Eastman Kodak's 343 State Street Rochester New York headquarters in 1937.)

TY-3. Lieutenant Commander Jack Litsey and his VP-120 Privateer flight crew.

MB-9. View of main gate at Ault Field in 1946. Malcolm Barker's comment:"Two tall bldgs were chute repacking towers. Large multi wing bldg had a dining hall and may have been the BOQ. Married apartments are south west of gate where wife and I (Malcolm Barker and wife) lived after return from deployment. "(text in quotes by Malcolm Barker)

MB-10. Malcolm Barker 'on tour.' This Stearman he found at an air show would capture the attention of many WW II pilots.

MB-11. Mrs. Malcolm Barker at Whidbey Island, Washington, in 1946.

(Malcolm Barker's comment March 4, 2013, accompanied this photo of his wife. "Franklyn: You have mentioned lack of a car in early Whidbey days. Wife and I did not have a car until I returned from deployment. Truly do not remember how we got from Mt Vernon rail depot to Ault. Sure it was the kindness of someone who had transportation. Recalled some new 1946 Fords at housing and hangars. Sending picture of wife with a convertable and a sedan behind her. Was your friend Barney Rapp's sedan this color? Seem to remember you mentioning Barney was assigned to VP-120 and you to VP-107. Or do I have name wrong? "

Franklyn E. Dailey Jr.'s reply, same day." Malcolm, here is my reply. Barney bought one of those 1946 Fords, a sedan, blue on the outside. He loaned it to me to go get my wife Peggy, and our baby son, who were coming in on Northwest Airlines, landing at Renton Field in Seattle, probably July 1946. Barney had a dog. I asked Barney what had happened to the dashboard in his new Ford. Barney told me that war shortages led Ford to make the dashboard out of soybeans, and his dog chewed it up!"

NAS Whidbey Island Seaplane Base Closes. PBYs superseded by PBY-5A aircraft.

The 1946 closing of the NAS Whidbey Island seaplane base, located north and east of the town of Oak Harbor, WA, and situated on a body of water known at the Saratoga Passage on the opposite side of Whidbey Island from Ault Field, meant the end of service for the Convair line of seaplanes in the Pacific northwest sector. Those were key waterborne aircraft that began with the P2Y-1s, models of which operated originally out of NAS Sand Point, WA, in the 1930s, and were forward based at Sitka, Alaska. The pioneering that these aircrews and their support personnel did, by necessity, with their novel application of instrument flight techniques, led me to write about their achievments in "The Triumph of Instrument Flight," the cover of which is at the top of this web page. I will not repeat that essential contribution to instrument flight history, here. For base and forward base history, which I am covering briefly here, let it just be noted that those 1930s activities opened the original U.S. Navy air facilities at Kodiak, and at Dutch Harbor.

Eventually ,I hope to get to the origins of Navy air attack operations out of Attu , operations that became so important in World War II. Seaplane-only PBYs were active in that period and were joined by PV-1s and PV-2s. One book, "The Thousand Mile War," covers some of that history. This period saw a mix of surveillance and air attack operations.

But for most of the days of beginning in the 1930s, right down to the present, air operations involved intelligence. Central Pacific VB then VPB Privateer operations during WWII, while bombing and strafing missions were primary, included RCM, Radar Countermeasures; these were conducted both for intelligence, and for jamming Japanese radar installations. Claims were made in one published book that such operations stretched all the way north to Shemya. I have some doubts about that but will pursue the literature to see if I can connect the dots.

In 2012, both EA and P3 squadrons are supported at NAS Whidbey Island. The continuity of mission identity, RCM, or ECM, is continuous at least from 1946, and may exist earlier if those claims noted in the previous paragraph prove valid..

Some forward deployment Alaskan/Aleutian photos . (These PBY-5 and PBY-5A aircraft photos are in my (Franklyn E. Dailey Jr.) photo files but the credits have been lost, for which I aplogize.)

FED-1. Inviting for geologists; invites caution from pilots and crew

A PBY-5 Quite Alone on Aleutian Patrol; wind streaks, water, and clouds below

FED-2. Background scenes are best seen, at a distance.

Snow blankets Aleutian terrain backdrop for this Catalina. The 'Cat' wasn't named for terrain like this.

U.S Navy Flight Missions

I offer here just a fast trip through an early phase of theU.S. Navy aircraft mission subject. I begin with two phrases from "The Reluctant Warrriors" by Alan C. Carey. This is a Schiffer Military History book published in 1999. The book begins with the transition that wartime Navy squadrons in the Central Pacific were making late 1943, and early 1944, from PB4Y-1 Liberators to PB4Y-2 Privateers. (The squadrons covered were mainly VB-108 and VB-109. Later the "P" was added to include patrol along with bombing;' as in VPB; adding the P also meant adding information gathering to bombing. But bombing took priority for those warfighting squadrons.)

From page 9: "Privateers were extensively equipped for Electronic Countermeasureswith radiodomes housing an APA-17HF/DF; an AS-124/APR intercept receiver; an AS-6/APQ-2B for radar jamming; and a bulge below the fuselage...housed an APS-15 surface search radar. (The authority given is Frederick A. Johnson in Bombers in Blue.)

From page 11: same reference, this: "Beginning in 1943, whenVB-101 became the first Navy land-based squadron to see action in the Pacific, Navy land-based bomber squadrons conducted daily reconnaissance missions, anti-submarine patrols, and bombing missions against the Japanese throughout the Pacific area from as far north as Shemya Island in the Aleutians to as far south as the Solomons...."

I don't doubt the action in the Solomons but I strongly doubt that central Pacific squadrons were covering Shemya.

The jammer was to reduce the effectiveness of Japanes radar so the principal mission, bombing, could proceed. An acronym often used then was RCM, for Radar Countermeasures, in lieu of ECM for Electronic Countermeasures. Our Privateers in 1946 had been upgraded to models of each of these early instruments, altho we used some different nomenclature. We had the equivalent sensor to detect radars, an adapter to examine their electronic output characteristics, a direction finder to get a bearing on them, and a jammer. The mission for those VB squadrons in 1943-44 was bombing so they used the jammers. The mission for Aleutian ECM fliers in 1946 was information, Soviet Siberian radar information, so we never used the jammer we had aboard in my 1946-48 experience.

I have discussed this briefly with Malcolm Barker, co-pilot navigator in VP-120, the squadron my VP-107 squadron relieved at NAS Kodiak in Sept. 1946, and he related that the ECM equipment was new in his squadron, that it was a subject of interest, but that the crews were not skilled in its use. Please note that the end of WWII, just months earlier, meant rapid unit personnel drawdowns, that squadrons would have many new people, and that many of the people signing on to stay on active duty had come from units that had flown ASW missions against U-boats and/or Japanese I-boats every day. Yes, my own PB4Y-2 in 1946, BuNo. 59645, still had a full complement of sonobuoys aboard. We often had to learn the ECM skill, ojt, for 'on the job' training. My informant is the same Malcolm Barker who supplied many of the K-20 photos shown above.

For a startling story of what happened to my PB4Y-2 BuNo. 59645, go to this website address:

Or, just go back to the beginning of this page, in the left column in blue, and hit the live link there labeled,

Aleutians Antisubmarine Warfare

Learn there how PBY4Y-2 BuNo. 59645 was shot down by the Soviets! And how this author found out about it.

The mission of FAW-4, as soon as World War II ended, became information gathering, less on countermeasures. ECM took center stage. But later, the msssion would no longer be assigned to a single airplane system.

(In 1952, while I was piloting a P2V, I did pilot a squadron plane to Ft. Wayne Indiana to take aboard a new APT-16 jammer from Capehart Farnsworth, the manufacturer. A jammer was still a member of the ECM configuration, just in case it might be needed. But by that time, my P2V crew and I, in OpDevFor's VX-2 squadron, were flying the P2V at 25,000 feet in a series of flights to determine the 'signature' our plane might reveal to ground radars. Later, many U.S. military aircraft were designed from the bottom up to be "opaque" to radar.)

The North Atlantic. (In the book pictured at the beginning of this page,, the North Atlantic is covered with "Operation Bolero.")

From a pilot's point of view, the north Atlantic routes and the north Pacific routes would present similar weather and geography challenges. The pilot would want the same aids to navigation to be in place and an air traffic control and communications capability that would enable him to safely conduct his flight from a departure point to an assigned destination.

Although not a formally declared participant, the United States in 1940-41 was engaged in the war in Europe well before it became actively engaged in the war in the Pacific. A northern rim airbase structure, along with air traffic control facilities, was put in place, "pre-war," measured by the timing of U.S. war declaration announcements, and was already engaged in heavy logistic movement responsibilities in that early timeframe.

For ship convoys, which needed air surveillance patrols from that same rim of bases, the term "Neutrality Patrol" was in force. Airborne logistics were conducted across that same set of bases; the logistics transport they did accomplish, vital materiels, special troops, and indeed, warplanes, were scheduled more tightly than ship convoys; their cargo was generally organized to be put in action upon arrival.

The ships moved many tons of cargo. It was slow and it was subject to U-boat losses. Schedules had to be made flexible enough to accept slippage. The aircraft could make several trips while the ship made one, and the aircraft could carry supplies specifically pre-ordered, as needed, to be used "today."

The calendar for North Atlantic war materiel supply was ahead of that which evolved for the North Pacific. There was an important difference. Canada and Britain were allies in the north Atlantic. Denmark had been over run by the Blitzkrieg and Danes were eager to cooperate in Greenland. The British had prepared the war footing for Iceland and our ground forces relieved theirs. Whatever U.S. deployed forces discovered was already in place in their establishment of operating bases in the north Atlantic was accepted as the starting point upon which we would build. No need to conjecture about the past. It was not our past. We were happy to have what was provided. We were happy it came from friendly sources. We did not have to wage a war or even a skirmish to obtain our bases. There was a lot to be done but we could begin with some legacy.

Alaska was different. It had been a territory of the United States since the previous century. Our citizens lived there and felt somewhat neglected. These citizens never let their second class (non-statehood) existence interfere with their fullest commitment to the effort to make Alaska ready for its critical role in readying for war, and war's prosecution when it came. Unlike the north Atlantic rim, active war did come to Alaska. Three important war engagements had a direct impact on our ability to provision Alaska and the Aleutian chain of islands for full aviation operations. These will be covered in enough detail to bring home the connection between aircraft operating bases and successful air operations. In the North Atlantic, readiness was never an issue. We took what we found and went on from there. In the North Pacific, readiness was the issue. Readiness was our own heritage. And at times it got in the way of fighting the war.

Home | Joining the War at Sea | The Triumph of Instrument Flight