- Barnstomers and Early Aviators

- Budget Flying Clubs

- Aviation Records

- VFR to IFR

- Early Airline Development

- Flight Across the Atlantic

- P-40s to Iceland

- Alaska Based Navy P2Y-1's

- Buckner Goes to Alaska

- Ship-to-Ship Battle

- Naval Flight Training

- NAS Instrument Training

- Aleutians Anti-Submarine Warfare

- Search & Rescue

- Gyros and Flight Computers

- Baseball Team Lost in Flight

- Tomcats and Boeing 777s

It was not going to be ASW, but ECM. Train and equip three Navy VP Squadrons for North Pacific rim patrols. Then, extend the surveillance south down the western Pacific.

1.-5. additions to this page, after an original entry of PB4Y-2 "Privateer" ECM flights in the Aleutians 1946-48:

1. War patrols out of Luzon 1944-45. (We go back to Radar Counttermeasures-RCM, and some good personnel photos.)

2. 1951-53 Korean War operations from NAS Sangley Point. P4M-1Q crew members Bob Tucker and Alfred Wellnitz.

includes a tale from a Naha interceptor that Bob and Al never knew

3. Shootdown in the Baltic. PB4Y-2 BuNo 59645 served this narrator well in the Aleutians ,1946-48. . Nation of Latvia commemorate the crew that was flying BuNo. 59645 when the Soviets shot them down over the Baltic. The aircraft's Bureau Number (BuNo.) was the connection that led an Italian tourist to this page. We've added some foreword and afterword to this story.

4. A Navy pilot in VP-107 returns from Aleutian sea duty and is greeted in a photo-op by wife and children at Ault Field.

5. Reunion Group from U.S. Army NCOC Class 4-68 Armor School Ft. Knox Kentucky. Most served in Viet Nam.

6. CDR Thomas Edward Hogan USN; was my second skipper in VP-107 and I'm hoping some reader will help fill out his story.

Copyright 2014 Franklyn E. Dailey Jr.

For closely related material, go down the left column to:

Alaska Based Navy P2Y-1's Sand Point ,Washington, to Sitka, Alaska, Navy seaplanes pioneered Aleutian Bases, Instrument Flight.

Buckner Goes to Alaska You read about him in the Koran War but he was making his mark earlier.

Ship-to-Ship Battle A surface ship battle between U.S. and Japan that speeded recovery of Attu and Kiska.

Search & Rescue PBY crew and Privateer Navigator meant life for three Army men adrift in a self propelled barge in a williwaw..

Or, stay here if you are interested in countermeasures. The book offered at the upper left covers not just the Aleutian missions but also the instrument flying involved in Aleutian Chain missions. Reader contributions have added material below that I have been privileged to offer on these web pages. Let's begin!

Navy official photo, sent to me by Braniff-Northwest pilot Bruce Sorensen, whose Dad piloted Lockheed PV-1s at wartime Attu.

This photo looks east toward the runway at Attu, during LOckheed PV-1 bombing missions in World War II. Many PV-1s never nade ut back from bombing targets at Paramashiro in the Kuriles.. Always overloaded, some crashied on or soon after takeoff.

This photo of a disaster at NAS Attu introduces readers to the North Pacific sweep of Fleet Air Wing FOUR activity asWorld War II .ended in 1945. That sweep extended from Kodiak to Attu, but Dutch Harbor's PBYs and Attu's PV-1s were the origins of the U.S. Navy's war effort in the air.. And Dutch Harbor, though attacked, remained un U.S. hands all through the war while Attu, along with neighboring Kiska were in Japanese hands for a time.

"Peace" began as the U.S. entered the year 1946. The pilots and crews of PBYs at Dutch Harbor and the PV-1s at Attu had lent their skills and their lives to a victorious postwar. Although the PBYs continued to fly and were joined by models of the PBM, seaplanes had done their duty. Even their Aleutian successor, shown in this next remider photo of a PB4Y-2 Privateer, would not have a long active duty Navy service life.

- Barnstomers and Early Aviators

- Budget Flying Clubs

- Aviation Records

- VFR to IFR

- Early Airline Development

- Flight Across the Atlantic

- P-40s to Iceland

- Alaska Based Navy P2Y-1's

- Buckner Goes to Alaska

- Ship-to-Ship Battle

- Naval Flight Training

- NAS Instrument Training

- Aleutians Anti-Submarine Warfare

- Search & Rescue

- Gyros and Flight Computers

- Baseball Team Lost in Flight

- Tomcats and Boeing 777s

Context: Instrument Flight, vs.Flight

Contact Author Franklyn E.Dailey Jr.

Winston Churchill, veteran British Cabinet officer in WW I, and Prime Minister (PM) with responsibilities for the British Empire in World War II, had been, along with his Conservative Party, peremptorily dismissed at the end of World War II by British voters. Clement Atlee, Britain's first Labor Party PM in many years ,succeeded him. Churchill came to America, the land of his mother, and gave a remarkable address at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri.

The date was March 5, 1946. The locale was not a chance choice. Missouri was President Harry Truman's home state. Truman had succeeded Franklin Roosevelt. Truman and Churchill had met informally while Truman was serving as Roosevelt's Vice President and had met again in Europe as principals at the Potsdam Conference. Westminster is a prominent London locale. Churchill's historic talk first introduced the world to the "Iron Curtain." Churchill then visited Washington for a series of talks. In "The Forrestal Diaries"(Viking Press), we find him on 10 March 1946 in James Forrestal's office. Forrestal was at that time the Secretary of the Navy and within a year he would be the first Secretary of Defense of the United States. Here is a portion of Forrestal's "Diaries" entry of that date:

"1. Russia: At three o'clock saw Churchill and was with him for an hour and a quarter. He was very gloomy about coming to any accommodation with Russia unless and until it became clear to the Russians that they would be met with force if they continued their expansion...."

"2. Task Force in the Mediterranean: He was very glad of our sending the Missouri (the U.S. battleship Missouri) to the Mediterranean but was very much disappointed when I told him that the plans to have this ship accompanied by a task force of substantial proportions had been abandoned...."

The effect of all this, at a much lower level.

So engrossed was I, fledgling pilot Franklyn E.Dailey Jr., in my effort to become an instrument- proficient Navy pilot, that a new era characterized by an Iron Curtain, and a Cold War, necessitating a primary mission change from Anti-Submarine Warfare to Electronic Countermeasures (ECM), was not immediate in its impact.. This change was not my first thought as I put on flight gear each day. Still, our Alaskan/Aleutian mission was not going to be ASW.

The mission was going to be ECM.

FAW-4 prepares for new mission.

Section of Whidbey Island. Aerial photo about 1946. revealing despite ovc; silver print from silver film.

photo courtesy of Malcolm Barker.

. Malcolm Barker was a Navigator-Pilot on a PB4Y-2 Privateer in VP-120 when I arrived at NAS Hidbey Island in early June 1946. I wasassigned to VP-107 and our first deployment was to relieve VP-120, which was completing its deployment at NAS Kodiak on September 1, 1946. Our paths never crossed at Whidbey, but from the time of working on this website in the early 1990s, Malcolm Barker has been a contributor. Let me quote a little of the e-mail that came with this photo. ".....most likely a K-20 Fairchild(camera) we used. Looks as though a PBY-5A has just departed the north ramp and a number of planes are parked on the apron.The Maylor pier at Oak Harbor is visible and the Victory housing on thehillside east of the city."

This second K-20 photo (above) from Navigaror/Pilot/Photogrpaher Malcolm Barker's files, emphasizes Ault Field about 1946. I have added a touch of enhancement.

Names of Key Places on Whidbey Island to Lend Perspective on the Photos Above

Ault Field, named after a Navy carrier pilot who gave his life in combat in the war in the Pacific against Japan, is at lower left in this photo,with one one long runway pointing up and slightly left in this photo, roughly southeast (130 degreees true adtually).The other long rrunway which begins at the lower left edge of this photo, points (250 degrees true actually) over the water roughly west to the right, out (none of this remaining description is seen in this photo) toward the Straits of San Juan de Fuca past Victoria BC on the north going west, and Port Angeles,Washington on the south. I have taken some words to describe this route because it was the safest conservative departure route for a loaded PB4Y-2 Privateer aircraft, often overloaded, to deploy to Kodiak.

From the Victory Home my family lived in, we called the body of water glimpsed toward the top left of the first K-20 photo, the Saratoga Passage. Our home, on a high point of land there 1946-48, looked down on the seaplane base, closed just before our arrival.

Malcolm Barker completed his operational training in Privateers before I did but our duty assignments had taken us both to such places as NAS Banana River, and some airtime in seaplanes. And while I worked for my first weekly paycheck at Kodak in Rochester NY, I invoiced a lot of Fairchild K-20 cameras because Kodak was a Navy supplier for the Fairchild professional line of cameras.

In the winter of 1946, a group of aviators and flight crewmen who had come from England, and the Azores, from the western Pacific, and from flight training bases in the United States, worked hard to form a cohesive air unit. The place that they gathered was the Naval Air Station, Whidbey Island, Washington. The island was located in the Puget Sound and the specific field they trained at was Ault Field. Three PB4Y-2 "Privateer" squadrons, VP-107, VP-110, and VP-120, each with nine planes, all assigned to Fleet Air Wing Four (FAW-4).

Schedules at NAS Shidbey Island,called for intensive day and night training flights to be conducted in preparation for departure one squadron at a time, on 3-month rotation assignments.While on forward deployment duties included flying the Aleutian Island chain, and be home based at NAS Kodiak.

It took time for us to realize that we were helping to define a new mission. I was assigned as a co-pilot for PPC Lt. Hugh Burris (he came from war duty at Dunkswell, England ,flying PB4Y-1s against the U-boats entering or leaving the Bay of Biscay). In VP-107, we were assigned to the crew of aircraft PB4Y-2 Bu. No. 59645. Our first sqadron deployment would be Sept. 1, 1946, and we would relieve VP-120 which had made its first deployment June 1, 1946.

Flight time and flight experience marked some of our pilots for selection as Patrol Plane Commanders. The remaining officers would share duty as co-pilots and navigators. The latter would also helpl with the increasingly technical orientation of the new mission requirements. These men (I was in this group) had not been trained for these new mission requirements, but the experience they were about to gain would form the basis for training future men and women who would become the specialists that we not only did not have but did not even realize were missing.

For some of us, the operational flight experience that we gained in 1946-48 in the Aleutians came while we were really still learning to fly. . When I arrived at NAS Whidbey Island, Washington, my flight log showed that 404.6 flying hours had been accumulated in single engine, twin-engine and four-engine planes at six Navy air bases, all in training. I was now beginning operational flying for the first time. And a lot of that time would be instrument flight.

Here are just a few more details on the PB4Y-2 The Privateer with a single tail (technically, a single vertical stabilizer which supports the plane's rudder) had evolved from Consolidated Aircraft's famed Liberator with its four engines and twin tails. The "Y" in PB4Y-2 was the Navy's alphabet designation for planes manufactured by Consolidated (which later became Consolidated Vultee Aircraft, short named Convair), and the "P" indicated a patrol plane.

The Liberator, as originally configured for the U.S. Army Air Corps was, in Navy shorthand, a PB4Y-1. Both the 4Y-1 and the 4Y-2 were heavily defended with dual .50 cal. guns in nose and tail turrets, and crown and belly turrets. The Liberator engines had superchargers to take her to altitude. Significant changes were made to convert the Liberator to the Privateer and the Navy's 1944 intention was to optimize the new model as the best land-based, long range, Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW) patrol aircraft that airframe, engine and electronics technology could create.

The Navy design, the PB4Y-2, in addition to the change to a single tail from the Liberator's twin tails, added twin .50 cal. turrets in the waists to replace the Liberator's single gun waist blisters. To provide the same stability and rudder steering action of the twin tail Liberator, the Privateer needed a single high vertical stabilizer/rudder combination. Although both the Liberator and the Privateer were equipped with four Pratt & Whitney R-1830 engines, design engineers had removed the Liberator's engine superchargers and replaced them (a weight replacement, not a functional one) with two stage blowers so that sustaining a 14,000-foot Air Traffic Control (ATC) assigned altitude clearance in a PB4Y-2 became a challenge whereas the Liberators regularly flew missions above 20,000 feet. The weight saved was quickly used up in other additions to the Navy patrol version of the aircraft.

At NAS Whidbey, we inherited some of the North African based PB4Y-2 aircraft that made their World War II debut late in the European conflict. These had had their engine cowl flaps opened up so that the inside of the nacelles would stay cooler in the local desert heat. There were also screens in the engine intakes to keep sand out of those desert-based aircraft. For Alaskan deployments, a retrofit was issued to redesign those desert cowl flaps so that they would snug down to the nacelle and keep heat in for cold weather flying. The desert sand screens were removed. Conceding that the Privateer could not climb above weather as surely as the Liberator, when it was in the "soup" the Navy Privateer was the better instrument flight aircraft.

One feature that endeared the Privateer to its crews in Alaska was its hot wing anti-icing system. For this hot wing, the Privateer paid a weight price in the form of a heat exchanger, but for Aleutian flying it was a godsend. The result was an all weather aircraft, equipped with the best in flight instruments, radio and radar, and a P-1 (Bendix) autopilot. (Other manufacturers, like Sperry, which pioneered them, made autopilots.)

The sight gauges for the main wing fuel tanks were on the forward side of the bulkhead that separated the bomb bay from the forward main cabin. They were on the port side of the hatch that led to the bomb bay. These were not electronic indicators or repeaters but old fashioned vertical glass tubes containing real aviation gasoline, the level of which told the crew the amount of fuel remaining. Most , but not all, flight crews were always careful about gas fumes. If a pilot opened his sliding plastic window bubble, just an inch, fumes rushed forward due to Bernoulli effect.

The Privateer could carry four self-sealing fuel tanks in the bomb bay, adding an extra 1200 gallons of aviation gasoline (avgas). With the wing tanks holding nearly 2400 gallons, the plane could top out just under 3600 gallons. For Aleutian flying, that gas capacity was the second best feature (after the 'hot' wing) of our PB4Y-2s. Its Pratt & Whitney R-1830 engines used 100/130-octane aviation gasoline. Leaned out, the 1830 could show fuel consumption of 50 gal. per hour, 4 engines burning 200 gph. With 2400 gal. in the wing tanks, and 1200 in the bomb bay tanks, theoretical flight time was 18 hours. Of course takeoffs took more, so 15 hours was going to be an exceptional flight.

The Privateer also carried ECM (electronic countermeasure) equipment, originally installed as an adjunct to its ASW mission. This ECM equipment, an "extra" in ASW warfare, turned out to be the key to our future missions in the North Pacific Ocean and Bering Sea. Our country had taken an increased interest in the Soviet Union and our forward flight area covered an important part of the Soviet Pacific frontier.

My First Operational Flight in BuNo. 59645; some surprises

Our crew's first flight from our U.S. base at NAS Whidbey Island, Washington to our deployment base at NAS Kodiak, Alaska gave us an inkling of the challenges to be faced in flight to the north. The immediate objective, to keep the plane and its crew aloft successfully, came fully home to me when I held the yoke on my first operationally deployed Privateer over Vancouver Island in 1946. Hugh Burris, the PPC (Patrol Plane Commander, the pilot in the left seat), informed me that he was going aft to see whether our #4 engine would have to be feathered. It had been giving hesitation indications accompanied by puffs of white smoke. The yoke is a multi-engine pilot's "stick." It is a stick with the bottom half of a circle attached to its upper extremity. It enables the pilot to control the position of the aileron and elevator flight surfaces. Rudder foot pedals control the rudder. The copilot of a dual control aircraft has flight surface controls identical to the pilot's.

Our aircraft had staggered up to just a 2000-foot clearance over Vancouver Island's rugged mountain range. We had had to maintain our takeoff configuration of half flaps all the way from Whidbey Island, Washington just to keep airborne. We were on instruments. The plane's allow lly allowed the over weight condition because a Naval Air Station based R4D (Navy designation for the Douglas DC-3) that was assigned to carry some of our squadron gear to Kodiak was down for maintenance. I did the "Weight and Balance" calculations and our aircraft was balanced OK but that did not tell the full story. What struck home to me with force in those moments was that Lt. Hugh B. Burris, USN, trusted me to fly the plane while he went back to look at a smoking (white smoke), sputtering Pratt & Whitney (P&W) R-1830 engine. As it turned out, the master cylinder's piston rod had failed. Burris made the decision to turn back, though he did not feather the engine because we were getting some useful power on #4 until just over the end of the runway on our landing flare out at Whidbey. At that point, the engine quit with a big puff of black smoke as fire engines raced down the runway behind us. Whidbey ceiling 700 feet, visibility 1 1/2 miles. My PPC out of a World War II Liberator squadron at Dunkeswell, England was one cool cookie. I was lucky to be flying with him. Our Navigator was Ensign Orville Hollenbeck, USNR, another very intelligent, serious and likable man. We were also blessed to have an experienced plane captain (crew captain) in Aviation Chief Machinist Mate (ACMM) Sellers. If any of the other crewmembers felt fear, it was not evident to me.

Ours had been the last plane in our squadron to leave for Kodiak. Navy 59645 was our number. Our hangar spaces at Whidbey had been vacated and another squadron had moved in. I strode back into our little family's living quarters, a half Quonset Hut, in flight suit and harness, holding my chest pack parachute under one arm. I was not expected home. After all, I had departed very early that morning on three months deployment. My wife Peggy looked at me and nearly fainted. She had never seen all that gear before and she assumed that I had parachuted from the plane.

There was a QEC (Quick Engine Change) for the R-1830 on an A-frame at NAS Whidbey and in a couple of days we would be on our way again. But, we took a different route, and again did not make it to Kodiak.

Pilot Burris, copilot Dailey, navigator Hollenbeck and plane captain Sellers joined in readying their plane for the second attempt to catch up with the other eight planes and crews of VPB-107 which had already arrived at NAS Kodiak, Alaska. The distress at finding our plane overloaded, needing half flaps, staggering over the mountains of Vancouver Island, Canada, with an engine spitting smoke, changed our flight planning for the second attempt. We were still overloaded. But we would now exit NAS Whidbey Island as the patrol plane we were designed to be, by flying low out through the Straits of San Juan de Fuca to the great Pacific Ocean. We had decent weather, about 1500 feet overcast, we passed Victoria B.C. on our starboard with Port Angeles, Washington to port. We saw the ferries that made regular trips between those two cities. After clearing the Strait, we turned northward just off the coast and over the water. Vancouver Island was on our starboard side, and we proceeded thence along the Queen Charlotte Islands, to a position off Annette Island, and there began the over water transit across the Gulf of Alaska direct to Kodiak. While we did not have engine trouble on this attempt to get to Kodiak, it proved to have its own challengees. As we were making ready to land at Kodiak, the whole Island 'disappeared.'

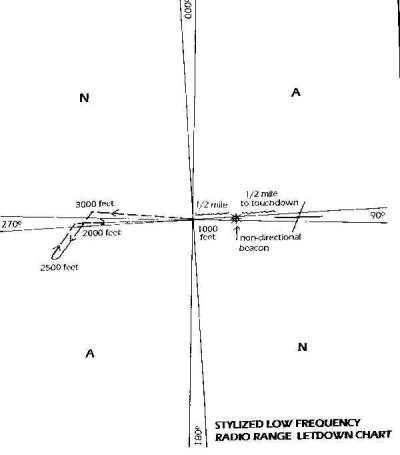

For how we actually made it to Kodiak some days later, read the book. I will close the record of this event here with a rendition of a low frequency radio range beam layout and a photo of aPB4Y-2 .

Illustration 12-Radio Range Letdown Chart (from the book at top left of this page)

PB4Y-2 Privateer This a a plane flown by VPP-1, a photo squadron I helped introduce to Big Delta Field near Fairbanks, AK, for Alaskan photo mapping assignments.\

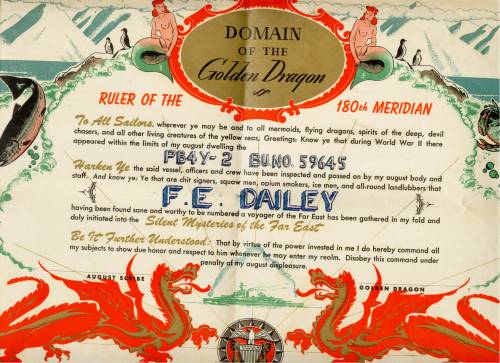

Let me take a moment here, for an event that all sailors enjoyed.

Aleutian missions took us frequently across the 180th meridian, so crews took a short break to celebrate, and here is a "certificate" to prove it. It took the lower latitude aircrews longer to get there, and some were already there.

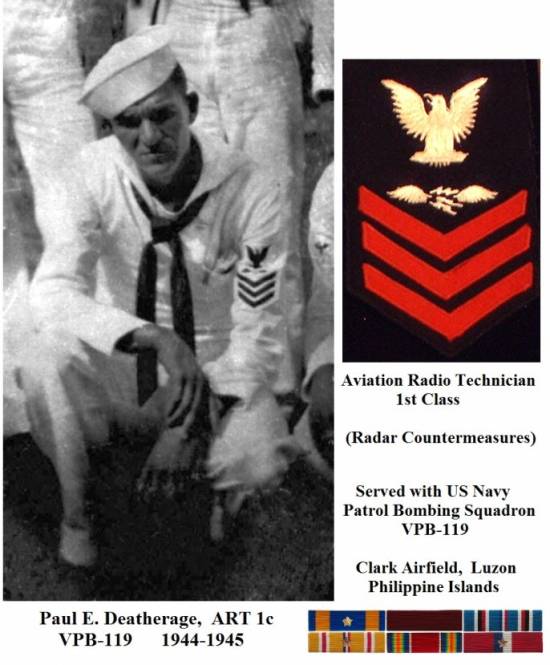

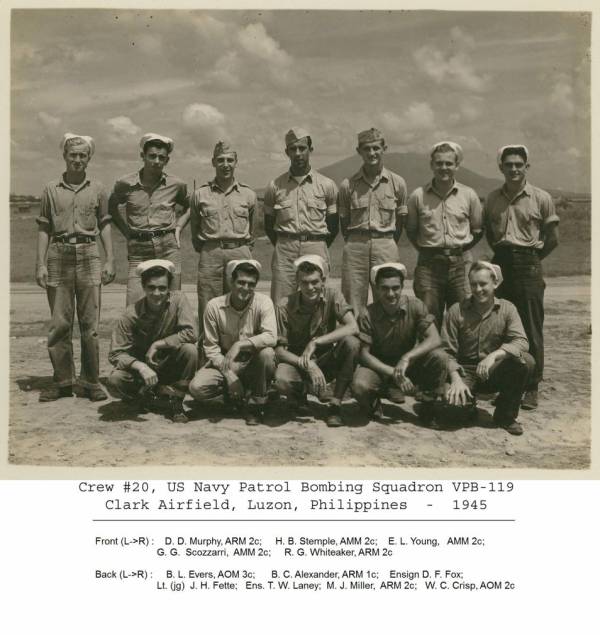

1. War patrols out of Luzon 1944-45. (to introduce Radar Countermeasures-RCM,, and some great personnel photos.)

This is a short throwback story to pick up the "R" of RCM, a different aspect of countermeasures, an active form. U.S. mission aircraft needed to 'take out' Japanese radars that helped their gunners shoot at us and bring us down sometimes. So we jammed their radars whenever we could.

An important global challenge had developed in 1945-1946. Although passive electronic equipment was aboard patrol aircraft by the latter months of World War II as an adjunct to and an assist to the anti-submarine warfare mission, the use of these aircraft primarily for such electronic surveillance missions was begun with no established protocols. The junior pilots just reporting to squadrons had little or no training in procedures for such missions. The pilots already there had no new mission training and very little briefing. It was not apparent, therefore, to the officers and petty officers that U.S. Navy aviation patrol missions in 1946 were in a change period, with day to day adjustments as part of a new kind of conflict. That conflict became known as the Cold War. One author titled his piece on the subject, "Protracted Conflict." He had it right. We knew what our immediate flight objectives were and we knew from our briefings that these were often based on what the previous patrol, yesterday, had adduced. Flight routes and altitudes were part of a "try it, and then we'll see from your results what to do next." I did not as I completed operational training in PB4Y-2 aircraft at Pensacola's North Whiting Field have any inkling that my impending Aleutian flights were a part of missions in flux for all U.S. military forces in 1946.

1944-45, VP patrols out of Luzon, in the Philippine Islands just retaken by MacArthur.

I go back in time, briefly here, to the retaking of the Philippines in WW II, and the years 1944-45. Squadron VPB-119 was flying radar countermeasures, RCM, flights out of Luzon,. Paul Deatherage, pictured below, was an Aviation Radio Technician 1/c, who sometimes manned the counteasures equipment on PB4Y-2 BuNo. 59411. His son, Dave Deatherage provided these next three photos, the first a collage.

A PB4Y-2 "Privateer" from VPB-119 flies radar countermeasures (RCM) mission out of Luzon in the Philippines in WW II.

Patrol Plane Commander Lt(jg) John Fette USNR, and his radar countermeasures aircrew, assigned to PB4Y-2 BuNo. 59411 of VPB-119, flying from Clark Field on Luzon in the Philippines in World War II. Paul Deatherage occasionally flew with this aircrew.

2. U.S. Navy Patrols: Recollections of VQ-1 Aircrew Members Bob Tucker and Alfred Wellnitz -Korean War, 1951-3

includes a tale from a Naha interceptor Bob and Al never knew.

( Narrator's Note. Two P4M-1Q operational patrol crewmembers relate some of their Navy experiences in long night flights flown by squadron VQ-1 during the years1951-53.

Here is what Robert Tucker tells us of his life after military service.

"Civilian life; after four years of naval service discharged in November, 1954, returned to college, graduated with BS degree in Political Science, continued my job with the Santa Fe Railroad that I had begun prior to naval service, advanced to upper middle management as a Train Operations Manager, and retired from the railroad after forty years of service." I (the narrator) asked for more on the P4M and crew duties, and on 10/9/2014, Tucker responsed:. "...the 4360 reequired a lot of maintenance from overhaul to complete engine change out. Our ground crew mechanics and plane captains/asst. plane captains were top notch. Shireman, Algred Wellnitz's plane captain, really monitored the 4360s inflight and I believe set a record for the most total hours on a 4360 before engine change out.....I always thought his (Wellnitz's) entire crew members were the overall best. All the crews were good, and I flew with all the crews, especially during my "on the job training," as directed by Chief AT Heinzelman, to become a qualified radar operator. Myself and two other men were the only ones that did not attend the 'a' school in Memphis, to become aircrew members."

...."The other two became aircrew radio operators. (They) were trained by Al Wellnitz and a Chief AL.".

Alfred Wellnitz' career, as related by him to this narrator:

"After obtaining his college degree, he (Alfred) worked as an electrical engineer for thirty three years, and then worked in real estate until age 73, when he decided to become an author; and has since written three novels ,and is currently working on the next one."

In response to a question from me (the narrator) where I had noted that the book Bob Tucker had sent me on the P4M-1Q used tthe term 'RCM,' Al Wellnitz commented,: "We were not equipped to jam. We monitored CW communications during the flights and used the same frequency as the other patrol aircraft in the region. We did send hourly position reports which were encoded. Frank, you know that at the time, voice over the oeean out of VFR range was not very reliable. "By 1954, when flying with VR-5 (as a crewmember), Hawaii to Japan, I found the Air Force had established pretty good long range voice on that route, but the Navy used it as a backup, not as the primary means of communicting."

Summarizing, two P4M aircrew members, who served during the Korean War, 1951-53:

Two men, Bob Tucker and Al Wellnitz, manned radar, Tucker, and radio, Wellnitz, aircrew stations , on long flights, with the radar supporting the navigation function when appropriate, in U.S. Navy P4M-1Q Mercator patrol aircraft, during the Korean War. The experiences they relate occurred in 1951-53, beginning three years after my own experience ended in the Aleutians in PB4Y-2 Privateers, and 50 years before a Navy Lockheed EP-3 (a P3V) aircraft made an emergency landing on Hainan Island. For many of those intervening years, models of the Lockheed P2V were on patrol in both the Atlantic/Mediterranean and the Pacific.

Tucker and Wellnitz crewed a graceful bird (photos later in this piece) that I knew little about until Bob Tucker e-mailed me in the summer of 2014. It was Tucker who suggested to Al Wellnitz, another man in their VQ-1 squadron at NAS Sangley Point in 1951, that the latter could add to what became a significant contribution to Navy VP history for me. As a reminder, I have taken on the role of narrator for their story.

We take up the background sory: After a peace was signed with the Japanese on the USS Missouri in August 1945, war re-commenced for the U.S. and UN allies, when the North Koreans invaded South Korea on June 25, 1950. One could make the case that war had taken little time off in the 20th century.

The basic elements of this writing will be "people, places, planes, and politics. Not in that order. 'Planes' mean flight operations. Two veterans of those operations recall their Korean War flight experiences. The narrator (me) is a World War II U.S. destroyer combat veteran but while still on active duty, by 1945 as a Navy pilot, was only peripherally engaged in what is known as the Korean War. 'Politics' means world politics. Part of my duties as Project Coordinator in Squadron VX-2 at NAS Chincoteague VA, I supervised readying F6f-5K Hellcat drones, fo be launched from carriers to fly bombs into the entry to rairoad caves in North Korea.

World Politics; how they influenced Navy VP operations

My (the narrator's) U.S. Navy flying experience began when World War II had just ended. Three flight squadrons, VP-107, VP-110 and VP-120 were home based at NAS Whidbey Island WA and forward based at Kodiak, Alaska. Some years later, while engaged in background reading for my book, "The Triumph of Instrument Flight," I needed to find out if there had been a link between our Aleutian flight operations, almost all Electronic Countermeasures (ECM) patrols under instrument flight conditions, and the U.S. international position in the post World War II period. I discovered James Forrestal's "The Forrestal Diaries."

At a meeting in Washington, March 10, 1946, between Secretary of Defense James Forrestal and Winston Churchill (after Churchill and his Tory Party had been turned out by the British voters) the two men agreed on the need for the U.S. to remain part of the European military structure, principally because of the threat of the Soviet Union. This meeting occurred just after Churchill's memorable speech in Missouri containing his citation of an "Iron Curtain" that he related to what was becoming the 'cold war.' President Truman facilitated both the meeting and the speech. I cite these events as having a more than happenstance connection with the U.'S. Navy's continued exercise of its air reconnaissance capability even though World War II had ended.

Soviet Russia had entered World War II in the Pacific at its very end, in 1945. China, whose people had taken inhumane treatment from Japanese Army troops during the latter's repeated incursions into China proper, had turned Communist with the defeat of the U.S. friendly government of Chiang Kai Shek. Both China and the Soviets were expressing their postwar military muscle in the Pacific. They both supported North Korea though the record had shown mostly tacit coordination among the trio.

Two places: Port Lyautey, and Sangley Point. in that order

Volumes Two, and Three, of the "History of the United States Navy in World War II," authored by Samuel Eliot Morison, provide what we need here on the first of the two places.

First, Volume Three, "Operations in North Africa Waters 1942-43." I was there, on the destroyer, USS Edison, DD-439, our ship providing close-in gunfire support off Fedala, for units of the Third Division. (See "Joining the War at Sea 1939-1945.") We were the central and main landing operation aimed at Casablanca. Just to our northeast, the old four-piper destroyer, USS Dallas, was trying to get special force units ashore for a specific objective. Dallas forced barriers in a river, then sailed past a fortress guarding the river. Between pages 130 and 131 in Morison's volume, there is a glossy page with four photos. The caption for the fourth photo tells it all:

"Dallas off Port Lyautey airdrome. Army P-40s have already landed at right. U.S.S. Dallas sails up the Wadi Sebou, 10 November `1942."

The final entry for 'Port Lyautey' in Morison's Index to Volume II, is "naval air station (pages) 245-246." About as fast as someone in Washington could get to a Remington or Underwood typewriter, an 'airdrome' had become 'NAS' Port Lyautey. U.S. operations at this base terminated in 1977. Thirty five years. A lot happened there. We will come back briefly in 1951 to set the stage for this story's connection with NAS Port Lyautey.

For the U.S., Sangley Point began as a coaling station for ships at the time (1898) of Admiral Dewey's entry into the Philippines in the 'Spanish-American War. It was later converted to oil. A U.'S. hospital was built and then 600 foot radio towers, for fleet communications. A low point, in Morison's coverage of Sangley Point, came in his Volume III titled "The Rising Sun in the Pacific." On page 206, Morison notes General Wainwright's surrender of the Philippines to the Japanese on May 6, 1942. Older citizens recall that this came after a long retreat on Bataan to the island of Corregidor. Key persons such as General MacArthur made it out, some by air, and some by submarine.

Denys Knoll and Charles Wechsler were Naval Academy graduates, close friends, both serving in the Philippines when the Japanese attacked. Knoll got out on a sub and later married my wife's cousin. Wechsler was part of a group getting ready to evacuate in a PBY to Australia. That aircraft sustained damage in a Japanese air attack and could not take the full scheduled load of evacuees. Wechsler volunteered to stay behind and became a prisoner of the Japanese. He was killed in a U.S. air raid on Japan in which his prison was bombed.

The Japanese were dislodged from Sangley Point by units of the U.S. Seventh Fleet on May 20, 1945. Sangley Point resumed life for the U.S. Navy, continuing with a succession of identities. "U.S. Naval Station Sangley Point," "Naval Air Station Sangley Point," and finally "Naval Base Sangley point." Those identities disappeared when the U.S. departed Sangley Point, and the Philippines, in 1971. The base had served the U.S. for 73 years less the three years the Japanese held it. During its service to U.S. Navy air units, I suspect those 600 foot radio towers focused the mind of all pilots.

Let me now fill in a lot of spaces in the next segment by noting: If South Korea was a 'client' of the U.S. for the Korean War, North Korea can be called a client of China. This was not the China of Barbara Tuchmans's "Stillwell Years," but a client of Communist China led by Mao Tse Tung, a China far different from the China friendly to the U.S. in the war against Japan.

1950-53 The Korean War

The war began June 25, 1950. My principal source is Max Hasting's book, "The Korean War." The early lines tell essential facts about the combatants and the lack of preparedness of one side, the U.S. and its United Nation's allies, for the war that the North Korean Communists, backed by China, unleashed.

From Hasting's Foreword: "The United Nations suffered 142,000 casualties in the war to save South Korea from Communist domination." Hastings was writing in the 1980s and made mention of the U.S. casualties in Viet Nam. He noted that, in Korea, U.S. casualties may have exceeded those in Viet Nam. The U.S. names on the Viet Nam 'wall' in Washington DC counts over 58,000 conflict deaths, and is, in 2014, still rising. The 'casualties' the UN suffered in Korea meant 'deaths.' Again, still rising.

In a chapter 'The Intelligence War," Hastings makes no mention of air intelligence. He does cover a 1950 expedition to air drop forces near a North Korean rail tunnel, in order to plant explosives to close the tunnel. In a chapter, "The Air War," Hastings does not cover intelligence.

Hastings relates, in acute detail. how North Korea made its well disguised, boldly planned, and devastating surprise attack on June 25, 1950. The South Korean Army was completely overwhelmed, outgunned, outmanned, and out trained. It had no answer for the ground and air assault unleashed from the north, and could not even intelligently communicate its plight to its U.S. ally.

The U.S. had ground forces on the Korean Peninsula, south of South Korea's defensive lines.

The U.S. also had its Pacific Fleet. Other nations would contribute land forces. Canada and England would add combat troops. Notwithstanding, North Korea came close to winning it all.

Harry Schmidt was a U.S. Air Force combat pilot on duty in the combat zone during the Korean War. He did night intercepts in the 2-place F-94, in that combat zone. Later, he became a test pilot for USAF, flying the latest supersonic jets. His last active pilot service found him working for Pratt & Whitney as their test pilot. He has written a book covering some of these experiences so I asked him to comment on his night interceptor operations.

Harry Schmidt , commenting on his Korean War USAF interceptor pilot duties at Naha, Okinawa: In an e-mail dated July 7, 2014

Hi Frank: The Navy planes operating out of Okinawa ..... they flew over China at night and were approaching Naha Okinawa at about 3am for fuel, coming from the west without flight plans. Obviously GCI thought they were possibly hostiles. We intercepted them about 100 miles west of Naha, flying low through the island peaks out there. The intercepts were hairy (low altitude, blacked-out targets, weaving thru the islands, etc.) As I recall, some were P2Vs or P4Ms. Great memories of a different time.

Best regards. Harry (Narrator's note: We will come back to a book Schmidt has written, for some specifics.)

We go now to U.S. Navy air operations at NAS Sangley Point.

In the short time it was known as the Naval Air Base, Sangley Point, the facility had gained an 8,000 foot runway, with instrument landing and air navigation aids, to serve the U.S. Seventh Fleet. No GCA. The air operations of interest in this story began in 1951.

Recollections of two Navy Airmen.

Bob Tucker served as a Navy AT-3 during his tour at Sangley attached to with VP-1Q , flying P4M-1Q aircraft.

Alfred Wellnitz served as a Navy AL-2 and AL-1 during his tour in the same squadron. Wellnitz arrived at NAS Sangley Point for his tour slightly before Tucker. The two would know each other and occasionally fly in the same flight crew. The squadron had four P4M aircraft and Lt. Harry Douglas USN was the Commanding Officer. He flew as PPC, Patrol Plane Commander, the command pilot, in one of the four P4Ms.

Bob Tucker's primary flight station was the radar and Al Wellnitz' primary flight duty was communications. Communications included a Morse code key. That was always considered more secure than voice. Like most Navy flight crews, the men often rotated flight duty stations and constantly trained as backups for each other. Wellnitz relates teaching others to key Morse code and some acquired enough proficiency to man the key during flight operations.

Both men served as crew members in P4M-1Q aircraft during a period in which their aircraft made lengthy patrols, as Wellnitz has put it, "from Vietnam to Vladivostok." ( I will try to remember to discuss fuel load as it related to flight duration, later.)

Bob Tucker 1st e-mail.

Re: instrument training for the junior pilots of the P4Ms stationed at NAS Sangley Point: (note: PPC stands for Patrol Plane Commander)

"As I mentioned earlier, there was no GCA at Sangley. For additional training of the junior pilots, some were Ensigns, some Lt jg's, we would fly to the Air Force base at Clark Field and the PPC would put them "under the hood" and we would make GCA approaches with them flying the aircraft. When a typhoon was forecast to hit Manila or Cavite (Sangley Point is on Cavite), we would fly our aircraft to one of the bases on Okinawa.

I'm sure we made some GCA landings at Okinawa from time to time. When necessary, for the B-29's stationed on Okinawa to fly away from forecast (weather), Sangley accepted all they could. I remember that soon after they landed, their navigational radar operators would come to our electronics shack and ask one of our technicians if we could tune up their radar. These B-29s were used to bomb North Korea flying from Okinawa. Some, not all, of our patrols from Okinawa were along the North Korean coast and then further north before turning back to Okinawa.

"Frank I am enjoying these electronic sessions. It would certainly be interesting if we could locate and communicate with someone who was stationed at Morocco and flew their P4M missions from there. I have never been fortunate to have found such a person."

"Speaking of having been fortunate to have found such a person, I searched for many years among your Naval Academy graduates that I have served with or met in civilian life and asked them this question, "Have you ever known an enlisted person who was chosen from the fleet to go to the Academy"?

While stationed in the Philippines, 36 of us, only two of us from our squadron, were given an eight hour exam to see if we could qualify to attend the Academy. We were told that it was possible that one percent of each freshman class could be admitted if they passed the physical and this exam. We took the physical prior to the written exam. None of us passed the written exam.

Two years ago, while on a cruise I met and talked to a gentleman who was a retired Captain and was a graduate of the Academy. Of course, I asked him this question, and he replied that I was "looking at one." He said he was a 3rd Class Corpsman when he took and passed the test and graduated from the Academy. I would have been proud to have accomplished that. " Bob" (Tucker)

Tucker 2nd e-mail

The pilots and plane captains were thankful for the jets when they had to be used when a 4360 (engine) was shut down. It was a more quiet ride. The plane was able to fly with the two jets alone, so I had heard. I never experienced that. But, Al Wellnitz reports that both piston engines were shut down on a flight he was on and the pilot made a landing in the two jet configuration and all aboard breathed a sigh of relief.

Severe weather conditions and operations in the Philippines can be encountered during and while being on the fringe of a typhoon. VFR landings at NAS Sangley could be marginal. On one particular return from a patrol, the control tower informed us that IFR existed, and since there was no GCA there, we would have to divert to the Air Force base at Clark field, 41 miles from Sangley where they had GCA. Lt. Douglas (the PPC and the CO of the squadron) told them to light the runway up, "We're coming in." He then told me (the radar-man) to line him up with the runway the best I could. My radar had a 2 to 200 mile range, and from 2 miles in, ground clutter normally filled the scope. I turned down the radar gain to reduce the ground clutter, gave the pilot directional information to line the plane up on the runway, and the pilot 'broke contact' and landed the plane.

Narrator's note: In the Aleutians, at fields where no GCA was available,we made those kind of landings in the PB4Y-2 aircraft with APS-15 radar. Not often, but I can recall three such landings. Harry Schmidt's backseat radar operator in the F-94 helped him land safely at Naha in those conditions. Radar operators saved a lot of pilots and crews and aircraft.)

Tucker 3rd e-mail

Frank, I do not know if you are aware that the 4360 engine on our plane was equipped with Hamilton Standard props which had reverse pitch, and the pilots used that feature when landing. The J-33 jets were not so equipped.

On occasion when one of the 4360 had to be shut down, the jet on that side was fired up. I believe I mentioned earlier that the jets used the same fuel from our 4200 gallons fuel tanks.

Consumption per hour for one of the J-33s was considerably greater than the 4360.

The pilots really loved flying this plane with all of its performance capabilities. On one patrol we were flying through the fringe of a typhoon north of Formosa which was producing considerable turbulence at 8,000 feet. Lt. Douglas told me to go forward to the navigation area, just behind the nose turret, and tell Lt. Taylor to assume co-pilot duties since Ensign Davidow was not large enough to help him hold the plane in the air. Lt. Taylor was approximately 200 pounds while Ensign Davidow weighed about 145 pounds. Ensign Davidow assumed navigator duties.

We finished the patrol, but it was the roughest one I ever flew.

On another patrol sometime later, with I knew it was time for a position fix and a course change. I waited for the request for the fix, and I waited a very short time longer, and still had not received the request for the fix. I knew where we were headed if we maintained that course, and I flipped the Standby/Run radar switch to Run. The land mass return on the scope was bright and reflected off my face. I immediately called Lt. Douglas to turn to (course) 090 degrees which he did. Our altitude was not sufficient to clear the mountain that we were approaching.

The radioman position was directly across from me on the starboard side. He saw the scope reflection on my face and knew as we made the turn that some communication had failed. Radar operators always had a copy of the navigation chart prepared by the navigator which he gave to us following the briefing for that particular patrol. That kind of backup was practiced in many different ways.

The APS-33 radar had the Standby/Run switch to keep the radar from constantly running if left in the Run position which would allow the bad guys to get a fix on us. Since I was always aware of the navigation plot, I knew when a fix was to be taken so I would position the 360 degree rotating antenna on the approaching intended target with the radar still on Standby. This allowed me to flip to Run position and confirm the land mass target almost immediately and then flip back to Standby. The navigator's Repeater scope allowed him to see what I viewed and he confirmed our position. I truly enjoyed my duties and responsibilities.

Another feature of the APS-33 was to utilize the True or Relative bearing position fix type of navigation. Two of our junior pilots had been shipboard officers prior to pilot training. They used True bearing navigation. All the other junior pilots who had never served aboard a ship used Relative navigation. I found this to be interesting and enjoyed either type.

Bob

Tucker 4th e-mail

The following description is of an unplanned flight on a late evening in 1952.

We had flown a regular patrol the day before, and were to be off a couple of days. The duty officer came to pick me up at our quarters and said the skipper, Lt. Douglas, wants you to come to the operations hut. On arrival he informed us who would be a hurried partial crew, one radioman, only the plane captain, the three pilots, one being the navigator as usual, no ordnanceman, no ECM operators and (plus) me, the usual navigational radar operator would be the crew.

Lt. Douglas had received an urgent call that we were to take off and search for a Russian submarine that was supposed to surface in a bay and off load supplies to the Huks, Philippine Communist guerilla, during the night of this full moon. We were to fly very low and use the landing lights as search lights. I was to stay on the radar and make sure we did not fly into a mountain during the several back and forth passes. We were to stay over the bay and near the island shore. After several minutes of searching we never found a submarine nor sighted any activity of any kind. Lt. Douglas said we would take a rain check and return to Sangley. Of course this was not our usual mission, but interesting. No such flights were ever performed again. I wondered who had ordered us to make this flight and search, but Lt. Douglas never told us.

You asked about other duties performed during our patrols. During the approximate six hours we were in the combat zone, I manned the nose turret for two hours when the senior radioman manned my radar. The two radio men had their two hours in the turret also. The plane was equipped with an electric stove located near the rear turret, The ordnanceman served as our cook, and we enjoyed one cooked meal during the patrols. He manned the rear turret the entire six hours, The plane captain and assistant plane captain manned the upper deck turret three hours each.

(Our P4M aircraft and our crew practices) allowed us to operate much farther north than a patrol from the Philippines would permit. We liked Okinawa since the Air Force chow hall had fresh eggs and fresh milk , not at sangley point nas.

I had been trained that if I turned "the gain " down on the radar you could get rid of some of the ground clutter from close range and still pick out the target. In one important (vital, actually) case, the target was the runway which was actually a very short and narrow peninsula, that stuck out into Manila Bay, that the runway was built on. I did what I was told to do, and about a mile out I told him (the pilot) we were lined up and he (our pilot, Douglas) landed using reverse pitch as usual.

I'm sure the Air Force pilot you speak of saw our planes on Okinawa often since all of our crews would alternate operating from there for a week. We flew out of either Naha or Kadena. This allow

At this point I (the narrator) am working from the body copy of Tucker's e-mails and I, the narrator (do some filling in)

On July 20, 2014, at 2:32 PM, Bob Tucker wrote:

The pilots and plane captains were thankful for the jets when they had to be used when a 4360 was shut down. It was a more quiet ride. The plane was able to fly with the two jets alone, so I had heard. I never experienced that. Weather conditions and operations in the Philippines can be encountered during and while being on the fringe of a typhoon (so) vfr landings at Sangley nas could be marginal. On one particular return from a patrol the control tower informed us that ifr (instrument flight rules) existed, and since there was no GCA there we would have to divert to the Air Force base at Clark field, 41 miles from sangley which had gca. Lt Douglas told them to light the runway up, "we're coming in". He then told me to line him up with the runway the best I could. My radar had a 2 to 200 mile range, and from 2 miles in grounded clutter normally filled the scope. (clutter made it harder to 'see' the runway.)

The pilots really loved flying this plane with all of its performance capabilities. Sometimes they were intercepted. And, most often the intterceptors were friendly, though the event 'passed in the night" largely unkown to the P4M crews. Here is one such event.

I have received permissions from Bob Tucker and Alfred Wellnitz, to reproduce the foregoing information, credited to them, on this website.

A P4M is intercepted by a 'friendly' at night. This occurred during the Koran War in 1951 or 1952.

In pilot Harry Schmidt's book, "Flying the Early Jets, " there are 33 events that serve as chapters. Event #15 begins on Schmidt's page 44, and is titled, "Intercepting the Navy." All these actions take place at night, often in instrument conditions. This is the Korean War, and Schmidt's F-94 jet is a two seater with pilot and radarman; no aircraft have filed flight plans, and pilot Schmidt, once on patrol, receives and transmits to GCI, Ground Controlled Intercept. He does use a local frequency for takeoffs and landings at his unit's airbase at Naha on Okinawa. The two paragraphs below are the last two on page 45 of Schmidt's book, and the airborne intercept is accomplished by two F-94s rather than the usual one; the object of using two F-94 interceptors is to let the "Navy," in most cases a P4M aircraft, know that they have been intercepted. I, the narrator, have concluded that World War II's IFF, Identification Friend or Foe, is no longer in existence. Here, in italics, is USAF pilot Harry Schmidt's description of this intercept.

Very carefully we (two F-94 intercepor aircraft) went dow nanother100 feet, and that made all the difference. We now could see the Navy plane, only a few hundred feet ahead of us and slightly above. We closed until we were right alongside his right wingtip. We could easily see the copilot outlined by the cockpit and instrument lights. He wasn't looking outside. They possibly could have seen us if they were looking for us, but they felt comfortable with the fact that the known interceptor was sitting right above them at 1000 feet...they did not know about the second F-94.

And then to implement our retribution....I slowly pulled ahead of the Navy plane so that we were perhaps 200 feet in front, at the same altitude, and slightly offset to the right. Then I lighted the F-94 afterburner and a sheet of flame the F-94 shot from the back end of the F-94 lighting up the sky. We imagined fright (hopefully even wet flight suits) in the Navy cockpit. Bob (the other F-94 pilot) and I returned to Naha and within a few hours our all-weather squadron teammates were celebrating our victory over the Navy. Just like the Army/Navy football game. We finally won. What risks pilots take to make a statement! Although we had that one victory the Navy continued with their earlier practice. Our victory was short-lived.

Bob Tucker forwarded documents and reports that add to the history of the P4M Mercator.

At this point, I offer a list documents published by others, that Bob Tucker forwarded to me in a Priority Mail packet postdated Sept. 14, 2014. I cite this material as relevant to the history of the P4M Mercator aircraft in operations in the Pacific, based from NAS Ssngley Point, and printed material based on records of P4M flights made from NAS Port Lyautey in Morocco. Herewith, the list:

Corrections to Dailey website entries for Korean War ECM efforts, noted as of Sept. 12, 2014. (these also contained in a later e-mail from Bob Tucker, and to the best of my ability attended to by Sept. 28, 2014.

Cold War/Hot War Evolution of ECM Aircraft-U.S. Navy Loss or Damaged Aircraft 1946-1959

Aviation "Enthusiast Corner-P4M-1Q Aircraft )contins a photo)

One pager on the Martin P4M Mercator with photos

Navy Patrol Wings, featuring the Mercator

HMS Kite diverted to rescue of4M-1Q Mercator; report of an aircraft based at NAS Port Lyautey

Intrusions, Overflights, Shootdowns, and Defections During the Cold War and thereafter -59 8.5x 11pgs

North Korean MIG-17 attacks P4M-1Q Mercator. 2pgs, also recalls earlier attack that downed P4M-1Q

Aviation Enthusuast Corner-3 page collection of pilot/crewmember comments on P4M-1Q; 13 signed comments including one from Robert Tucker. Remarkable affirmations of broad qualities of this aircraft from the crews that flew the aircraft on dangerous missions.

The Martin P4M "Mercator"

Here ,are two views of one of the P4M aircraft, in a squadron in which four aircraft were assigned..

Let me begin with some basics on the aircraft ,as related by Tucker and Wellnitz. Two 4360 P&W radial engines, four rows of seven cylinders in the engine. A "corncob' engine as I heard it described in 'my time' as an aviator.. Used in few aircraft, the B-36 being one. In the lower section of each nacelle, behind a shield that could open, was a Westinghouse J-33 jet engine. This was truly a transition airplane. Startling to me was Tucker and Wellnitz affirmation that the same fuel, 115/145 octane, was supplied to run both the piston engine and the jet engine.

P4M aircraft based at NAS Sangley Point, Philippines, in 1951 during the Korean War.

Front view, P4M aircraft.

Both photos by Alfred Wellnitz.

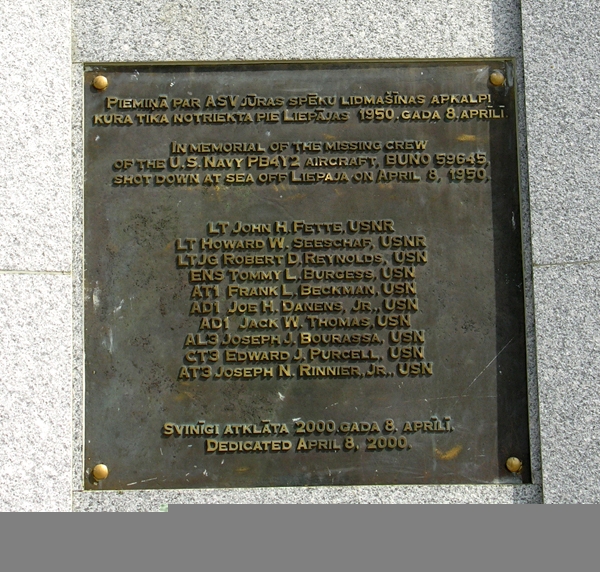

3. A Sad Sequel for PB4Y-2 BuNo. 59645, and Pilot Navy Lt. John Fette and crew. (see names on the monument plaque below)

"I'm sending you better pics. The one I sent you with the plaque I had taken from the net – just throw it away. Here are those I took during my first visit in 2005. You can see the monument much better here, the pictures are mine (Alessandro Nati Fornetti) and of course you can put them on your website.

The monument is along the shore in Liepaja, Latvia, exactly at 56°30'33.50"N, 20°59'28.23"E."

In italics above, is the first paragraph of an e-mail, sent to me on 01/18/2012, by Alessandro Nati Fornetti, a publisher in Italy. The entire "connection" that Alessandro Fornetti was able to make between a plane shot down over the Baltic Sea in 1950, and a plane I had flown as the assigned plane for my crew in the Aleutians June 1946-Oct. 19, 1947, was a total surprise to me. And, at first, to Alessandro. My last flight in 59645 was a memorable night flight from NAS Miramar (southern California) to NAS Whidbey Island (Washington State) and the log book remarks show "instruments, moderate icing." Flying in the left seat was Lt. Allan LaMarre. We had taken a 'five on top clearance' and the cloud layer buildup, as we got over Oregon, had forced us up to 12,500 feet. The aircraft began to wallow, lose heading and altitude. I checked the pilot, and he was slumped over. I took the controls and obtained a descent to 7,000 feet from Portland Approach Control.. Al had anoxia. He had passed out. The oxygen at 7,000 feet slowly brought him back and he resumed control for our landing at Whidbey.

My flight log book shows no flights in 59645 after that date. It was a tired bird by then, and I suspect it was flown back to rear base overhaul. From that date forward until June 3, 1948, PB4Y-2 BuNo. 66277 was the aircraft I flew most of the time.

In April 2005, Alessandro Fornetti and girlfriend traveled to Latvia. While there, Alessandro discovered a monument, and took the beautiful pictures below. In early 2012, Alessandro discovered this web page ,and learned that I had been a co-pilot of PB4Y-2 BuNo. 59645, just two years before that plane, now assigned to another Navy squadron, had returned to Port Lyautey, Morocco, to begin a fateful journey to Wiesbaden, Germany, and there to get airborne on its final flight.

(Malcolm Barker, another NAS Whidbey Island Privateer pilot, separately from me, had just made the "connection" between an event in Latvia Iin 1950, and the plane to which I had been assigned as copilot for most of my three Aleutian tours. (The first tour my PPC was Lt. Hugh Burris, the second tour with a PPC named "Junior" Johnson, and the final tour with PPC and Commanding Officer of VP-107, CDR Edward T. Hogan USN. ) more about Ed Hogan, near the end of this page

Here, a sequence of three photos taken by Alessandro Nati Fornetti in 2005, to mark his discovery of an event of 1950 that Latvians cherished, so they marked it with conspicuous care, on its 50th anniversary.

This monument, erected at Liepaja, Latvia, dedicated in 2000, to mark the 50th anniversary of the date that a U.S. Navy flight crew in PB4Y-2 Privateer, BuNo. 59645, was shot down over the Baltic Sea by Soviet fighter planes in 1950. 2005 Photo by Alessandro Nati Fornetti.

Next another photo taken by Alessandro Nati Fornetti, again in 2005, showing the bronze figure at the top of the monument at Liepaja, Latvia.

Next below, a photo of the plaque on the Liepaja Latvia monument, honoring the U.S. Navy flight crew of PB4Y-2 BuNo. 59645, shot down over the Baltic Sea by Soviet fighter aircraft, in 1950. Photo taken by Italian publisher Alessandro Nati Fornetti. Flight crew names are clearly visible.

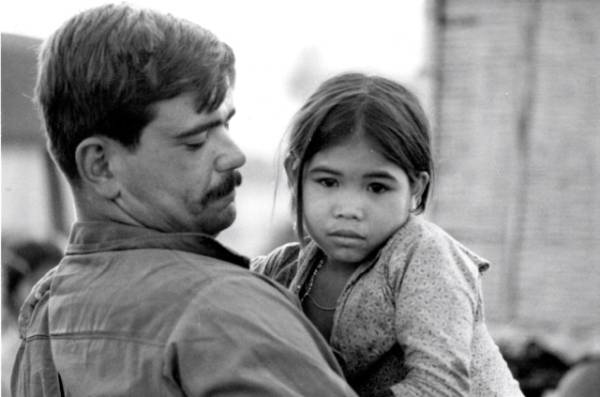

4. A Navy pilot in VP-107 returns from Aleutian sea duty in 1948 and is greeted by wife and children..

Next, two photos as U.S. Navy patrol plane squadron VP-107 (aka VP-H/L7 and VPB-107 at various times), returns from deployment at NAS Kodiak AK, to NAS Whidbey Island Washington's Ault Field on June 3, 1948 in a 7 hour flight from Kodiak. This had been the author's third deployment with that squadron and shortly after I received orders back to the East Coast for PG School. Both PB4Y-2s in the photo belong to VP-107, and the one on the right from which the author has just deplaned, is PB4Y-2 Bureau Number 66277. This photo is in the book. My log book also has a pasted-in-paper, with Squadron seal imprinted, affirming that I was a designated PP:C for this type aircraft.

Above, the author, after deplaning from PB4Y-2 Bu.No. 66277, after it landed at NAS Whidbey I. returning from NAS Kodiak AK. The aircraft is the one on the right in this photo, taken by the author's wife, Mrs. Franklyn E. Dailey Jr. ('Peggy'-now 92 years young.)

Pilot Franklyn E. Dailey Jr. meets his sons, Frank III (right) and Michael (left), on the ramp at Ault Field, NAS Whidbey I. Wash., after the return flight from his last deployment to NAS Kodiak AK in PB4Y-2 Bu. No. 66277, June 3, 1948. This photo was also taken by the author's wife, Peggy.

This ends some details here on Privateer deployments to the Aleutians 1946-1948. The book pictured at the top of this page contains a more detailed account of those deployments. There is an Order Book link under the cover picture. The only aircraft identified in my book by Bureau Number for Aleutian deployments was 59645, although when that plane was down for maintenance I did fly other Privateers on operational flights.

5. Reunion Group from U.S. Army NCOC Class 4-68 Armor School Ft. Knox Kentucky

In Reunion Sept. 25, 2014: Shown Here at Corps Plaza Memorial, Texas A&M

Across Top: Philip Dailey Richard Rumsey Jim Yaman Gary Falcone Mike Halterman

Second Row : Orville Smith Frank Rackstraw Becky Whitson Vic Lozoya Michael Park Mac Brown—Bugler

3rd Row "Bob Delehanty Jim Korey Manny Montanez

Front Center :Les Kampen

Becky Whitson is the sister of John Whitson, a member of the NCOC Class 4-68, who gave his life for his country in Viet Nam.

One reunion highlight, reported by Philip Dailey, organizer of this reunion, to his mother in Alpharetta Georgia, 94-year old Marguerite "Peggy" Dailey, was the perfect audio rendition of "Taps," bugled at the Memorial by Mac Brown, second row right in the photo. Mac was using a World War I bugle that Peggy Dailey purchased in an antiquie store in Massachusetts, "sometime," as best she can recall, between 1962 and 2007. (There will be more to follow on this event.)

Reunions like this bring out photos from a faraway country where many members of this unit were called upon to serve. Here are two.

Hamburger Hill 1969

Gary Falcone and Milynn Montagnard Village 1969

6. CDR Edward Thomas Hogan U.S. Navy

DOB: January 4, 1918.....DOD: August 21, 1981

Married Mary Louise Hall on August 15, 1943 (she was an Army nurse from Louisville, Kentucky; they met in Australia during the war)

May 1938: Graduated from Milliken University, BS in Administrative Engineering.

July 5, 1938: Seaman, 2nd Class USNR

November 3, 1938: took oath as an Aviation Cadet

September 30, 1939: Became Naval Aviator

November 1, 1939: Received single-engine pilot's license

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Between these red dotted lines, Lindsay Garrison adds more information on her grandfather, naval officer Ed Hogan. See below these listings of Ed Hogan's assignments.

March 1941: Ensign E.T. Hogan, USNR to USN

April 5, 1941: Ordered to Office of Naval Intelligence. (ONI)

April 11, 1941: Reported to ONI, Washington D.C.; subsequently assigned to U.S. Embassy, London, to work as Naval Observer.

May 10, 1941: Added assignment for flight duty with Royal Air Force Coastal Command, Lough Erne, Ireland.

May 10-15, 1941: Instruction, familiarization flights in PBY Catalina Aircraft for RAF pilots in Ireland, for patrol and anti-submarine duty.---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

December 1941: Reassigned to Pacific Fleet, saw "considerable action" against Japanese.

October 21, 1944: Based at NAOTC Jacksonville as LCDR USN; ordered report to NAS Hutchinson, KS.

1945: Completed advanced training in Hutchinson, KS. daughter, Marsha, born.

1947: Completed advanced patrol plane training at NAS North Whiting Field, Florida

1947: Completed general line school in 1947 at Newport, R.I.

Oct. 3, 1947: Appointed Commanding Officer of VP-HL-7 at NAS Whidbey Island, WA under FAW-4

March, April, May 1947 squadron deployed to NAS Kodiak, Ak

(VP-H/L7 became VP-27 in '48) still home based at NAS Whidbey Island, Washington under FAW-4.

March 19, 1948: son, Patrick, born in Seattle.

Feb. 1949: Deployed with VP-27 to Kodiak, Alaska.

July 1, 1949: Detached from duty as C.O. of VP-27

April 1, 1950: appointed rank of Commander USN

1950: Completed a guided missile course at Ft. Bliss TX

1951: daughter, Debbie born

1951-1954: overseas duty in Korean War; family remained in Mobile, AL.

1954- June 1955: Commanding Officer Airborne Early Warning Squadron Three (VW-3) on Guam Island in the Mariana Islands.

1955-1960: Exec. Officer, AIRDEVRON One (VX-1) Squadron based at NAS Boca Chica, Key West FL.

Feb. 1 1960: Retired from Navy.

Feb. 1960: Moved to Dallas, TX; employed as an engineer for Texas Instruments (whose equipment he'd been testing in the Navy while serving with VX-1.)

Fall 1961: Enrolled in courses toward a Masters in Mathematics at SMU, paid for by the Navy.

1968: Lived in Austin, TX; worked as "engineer/scientist" for Tracor, Inc.. (First of two listings for Ed Hogan , a life outline)

Now from a second e-mail from granddaughter Lindsay Hogan Garrison, more on Ed Hogan from an earlier part of his naval career.

Hi Frank, (02/17/2012)

It's so great to hear from you! I really enjoyed reading your additions about the fate of the particular plane (PB4Y-2 BuNo. 59645) you and my grandfather, Ed Hogan, once flew - how neat that Mr. Fornetti sent you those pictures. It adds another thread to the fascinating tale you weave about the evolving change in mission strategy during the Cold War. Thanks so much for sending this along -my family and I certainly appreciate it!

I've been looking through my grandfather's papers for anything about that mid-air re- fueling you mentioned. I haven't found anything about that specifically yet, but I will definitely keep looking.

There is quite a collection of material, all from the history project he was working on when he died. I don't remember if I mentioned it to you, but in the late 1970s, Ed began working on writing a history of US Naval Aviators involved in the "secret war" - referring to the U.S. military's aid and intelligence efforts for and with Britain before formal declaration of war in December 1941. This was all part of Ed's work as a "Naval Observer" with the Royal Air Force (RAF) Coastal Command for the U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence in 1940. It was part of a critical turn in the fight against the Nazis, strengthening Churchill's forces considerably as the British Navy was struggling against the German U-boats and warships; the American PBY Catalina pilots, including Ed, working with the RAF at that time in fact played a crucial role in the search, identification, and sinking of the German warship Bismarck, long heralded by historians as a major turning point in the war. However, as Ed began writing about it, these U.S. Naval Aviators were never recognized for their involvement, because disclosing their missions "could have placed them in jeopardy of charges of violation of the U.S. Neutrality Act," given that war had not yet been officially declared at the time of their service.

One portion of Ed's focus in this project was the role of the PBYs they flew then - the Navy sold the UK several PBYs in 1940 (Lend-Lease), and part of Ed's job with the RAF was to teach the Brits how to fly them (while also collecting & reporting info for the U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence about the war effort, so FDR could know what he was getting into should America decide to enter the war). He wrote about the plane's great range & how its' 22-30 hour endurance gave the British an enormous advantage in surveillance & reconnaissance, and that the first operational use of radar was on a PBY. I found one document where he mentions the fact that adding wheels to the fuselage later in WWII "ruined the excellent capabilities" of the PBY by cutting its' range by 1/3 or more. So, it's possible that he also wrote something about his involvement in trying to maintain the plane's range after that modification by refueling in mid-air, but I haven't come across anything like that yet.** I'm happy to scan & send anything I find that you might be interested in.

Anyway, thanks again for sending the updates. My family and I had a great time reading them. I hope you are doing well!

All the best, Lindsay Hogan Garrison **

**Ed Hogan told Frank Dailey of the effort made from an Aleutian base to refuel a PBY from a PB2Y Coronado (4-engine Consolidated seaplane) in the air, to give the PBY gas to get to Paramashiro and back. Ed never spoke a word to Frank Dailey, his co-pilot in a VP-107 PB4Y-2 Privateer while on Aleutian duty ,about any clandestine naval intel work that he, Hogan, had done while attached to the U.S. Embassy in Britain before the entry of the U.S. in World War II.

Some personal reflections on Aleutian flying by Franklyn E. Dailey Jr. Capt. USNR (Ret.) comment always welcome

The Aleutians, along with some Search & Rescue missions over cruel waters or grim terrain, was a challenge for pilots and aircrews.. Always "all weather." "Strength Five Bartows please!" "Tower, please report runway braking action." "You have it GCA!" Fortunately, some others in my new environment had a better appreciation for what was happening and eventually, I caught on.

65 years have now passed since the men of the first "tours of duty" following the end of World War II patrolled the air over ocean waters in their attempt to obtain the earliest possible knowledge of activities that might someday lead to confrontation with the United States. In the North Pacific, if we allow two years for a Whidbey Island serviceman's tour of duty, more than 25 sequential "tours," with complete changeovers of personnel have occurred. This spans a period begun by the last man in my squadron to go home in 1948 to the first man or woman to join a new millennium squadron at NAS Whidbey in a deployment rotation. With two or three squadrons at a time in that rotation, and nine planes per squadron, each squadron with 250 men and women, the rough calculation suggests that 20,000 of our military personnel have kept "watch" in the Pacific on just this one mission. Countless, boring flight hours have gone into thousands of logbooks. Death and tragedy have struck at takeoff, at landing, and during those long, long patrol hours. the Privateers had excellent flight performance records.

Or, consider the families involved. Almost three generations of U.S. service families are represented. Only the quiet sense of accomplishment shared by those who served and those who remember those who served, constitute the reward. Navy patrol squadrons at NAS Brunswick, Maine with forward bases in Iceland, have matched that achievement over the North Atlantic. And Connies (Lockheed Constellation aircraft) in the Dew Line along with U.S. Air Force interceptors in revetments along our coasts, always ready to scramble, have been another major part of these most obscure of all missions. All this has transpired for just one objective, to keep from getting surprised.

An important step in the organization of our defense forces occurred when the United States Air Force became independent of the United States Army. Long before this formal separation took place, as far back as World War II and earlier, the operational capability presented by the Army Air Corps segment of our armed forces was projected as an air force. I have not made any effort to examine any nuances in capability and acknowledge the possibility that I might occasionally have used out of date nomenclature in this story.

Eleven U.S. Presidents have gone to Congress 55 times seeking support of military budgets that include the aviation mission requirements that developed right after World War II. The aviation component of those postwar budgets have been presented, as budgets are designed to do, as a component of military activities "going forward." Interestingly, the budget battles that have found a President and a Congress in sometimes bitter and always well chronicled debate are sometimes better remembered than the operational activity those budgets supported.

Our preoccupation with Congress and budget confrontations tends to obscure what our Department of Defense budgets provide in forward areas. Partisan political battles make us weary. It is almost understandable that we then take so little opportunity to learn what constant vigilance means to our country and to the men and women who serve it.

How World War II advanced the art of instrument flight.

If I had maintained strict chronological discipline, the next paragraphs would have come before my own experience flying Privateer aircraft BuNo. 59645, touched on above. In writing of the advent of instrument flight, the main theme of my book, I covered Operation Bolero which involved B-17s being flown to Britain for the war effort, and having a P-38 on each quarter, tagging along. Such operations and then operational bomb flights over Germany, forced pilots to become instrument skilled as a byproduct of their missions.

The military patrol plane and bomber pilots of World War II, and their advanced design aircraft, with almost no recognition at all, had revolutionized long duration flying under instrument conditions. That was not their objective. They had to get there, and they had to get back. Getting back was often complicated by damage from hostile flak or from enemy fighter plane engagements. Adding to the complication for many of those missions was a home base in England under solid cloud cover often extending right to the ground. So, now add a side trip to an "alternate" landing field, often a strange landing field. The pilot flight skills contributing to advances in the art of aviation have been largely obscured because those advances were secondary to military objectives. I have not seen even belated recognition for performance these men and women claimed no credit for. Their sheer numbers and the scope of the training systems that prepared them, helped propel civil aviation into a 50-year period of unprecedented growth covering the last half of the twentieth century..

By 1941, on the North Atlantic rim, patrol plane pilots from bases in the Azores, England, Scotland, Iceland, Greenland, Labrador, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia and the New England States had begun flying countless monotonous hours that included minutes and seconds of bravery and terror. Takeoffs and landings were more than likely to be on instruments. Add fuel and pilot exhaustion in malfunctioning or AA-damaged aircraft systems, a terminal destination below aircraft landing ceiling and visibility minimums, and the record of triumph over adversity is an enviable one. U.S. Army, Navy and Coastguard airmen and their British and Canadian counterparts from Coastal Command made impressive contributions to the Anti Submarine Warfare effort against the U-boats. Many paid with their lives. When Admiral Doenitz ordered his submarine commanders to stay surfaced in groups for passage across the Bay of Biscay, he equipped his U-boats with AA guns and ordered anti-aircraft gunnery resistance to our ASW aircraft. The heavily armed Liberators would go in guns blazing during a depth charge run. Many times both aircraft and submarine combatants met their end.

This record is summarized well by author Clay Blair. In Volume II (1942-1945) of Hitler's U-boat War, author Blair writes, "But with the perfection of centimetric-wavelength radar, which was installed in big four-engine long-range bombers such as the B-24 Liberator, the B-17 Flying Fortress and the British Halifax, land-based aircraft vaulted to top rank as U-boat killers. According to Alex Niestle (a published German scholar), "they sank unassisted 204 U-boats and 30 more in cooperation with surface ships, a grand total of 234, nearly a third of all German losses at battlefronts.....All told, Allied warships were involved in 282 U-boat kills." For the entire statement, consult Blair's "Afterword," headed by the line, "Finally, a few words about the aircraft as a U-boat killer." This appears on page 710 of of Blair's Volume II.

What is not stated in those excellent war histories, simply because it was taken for granted, was that the military pilots of the ASW aircraft flying out of the British Isles, Iceland and Greenland, Canada and the Azores built up extraordinary instrument flight experience. A great deal of this experience would be fed directly back into the U.S. airline industry. Notwithstanding the attraction of airline flying, some of those pilots enjoyed military life and when given an opportunity to go "regular Navy," for example, chose that option.

By late 1944 and 1945, the B-24 became available in Navy models, first as the PB4Y-1 externally like the Liberator, and then the PB4Y-2. It was in the PB4Y-1 over the North Atlantic that my first Alaskan Patrol Plane Commander (PPC) attained his early instrument flight experience. In Alaska, two years later, he would be confronting north Pacific rim deployments, particularly flight in the Aleutians. For him, this involved a second major tour with long periods of instrument flying. At our deployment base, NAS Kodiak, Alaska, he and I as his copilot, first flew operational missions in the PB4Y-2 aircraft. That aircraft's main configuration changes from the 4Y-1 model have been covered earlier.