Early Aviators: Russell Holderman; news empire builder Frank Gannett

Leroy NY Airport, Financed by Jello's Pres. Donald Woodward; Ray Hylan and a Curtiss Jenny; Eddie Stinson and the "Detroiter" preserved by and flown at Pt. Townsend (WA) Aero Museum; Lockheed Electra 10 and Lockheed Lodestars were important aircraft in all sectors of early U.S. aviation

Copyright 2013 Franklyn E. Dailey Jr.

- Barnstomers and Early Aviators

- Budget Flying Clubs

- Aviation Records

- VFR to IFR

- Early Airline Development

- Flight Across the Atlantic

- P-40s to Iceland

- Alaska Based Navy P2Y-1's

- Buckner Goes to Alaska

- Ship-to-Ship Battle

- Naval Flight Training

- NAS Instrument Training

- Aleutians Anti-Submarine Warfare

- Search & Rescue

- Gyros and Flight Computers

- Baseball Team Lost in Flight

- Tomcats and Boeing 777s

Citizens around the world, including young people just learning to read and write, joined in the triumph of Charles Lindbergh's 1927 solo non-stop flight from New York to Paris. That flight spanned two calendar days, leaving Roosevelt Field on Long Island in the early daylight of May 20, 1927 and landing in the early evening at Le Bourget Field, Paris on May 21, 1927.

In different sectors of an aviator spectrum just emerging in the 1920s were barnstormers, mail pilots, military pilots, and very late in that decade, a few airline pilots. Soon to come was corporate aviation. The diversity in human interests is reflected in the fact that many pilots in these very different flying professions had come to aviation as the result of the impetus given to aviation by World War I. One of those was Russell Holderman whose flight career began in 1913; when I met him as pilot of a Stinson Detroiter that took my family aloft in 1929 at the Leroy, New York, airport, he was introduced as Lieutenant Commander Russell Holderman USNR; so had participated in the Navy's aviation buildup for World War I. As we shall learn, Holderman pioneered, in likely a substantial portion of his 28,000 flight hours, as chief pilot of corporate aircraft for Gannett Newspapers. Let me begin with barnstorming, rubber necking, and aviation record-setting.

The Curtiss Jenny and a Barnstormer

Two flights, known now to almost no living persons, come frequently to this author's mind. One was recorded in two small-town newspapers. The other was recorded only in human memory. These occurred within two months, and within two years, respectively, after Lindbergh and his Spirit of St. Louis made it to Paris.

In July 1927, a barnstormer came to my town, Brockport, New York, in his biplane. He landed on Gifford Morgan's farm, just east of the town. Morgan was a leading citizen in Brockport. After pilot Ray Hylan made his peace with owner Morgan for temporary landing rights, he solicited "ride" business from the "locals."

The Peters family lived just down and across the street from our home on South Avenue. Their eighteen-year old son, Stephen, had graduated from high school and was working in Ed Simmons' drug store for the summer. Steve was greatly admired by the small fry on our street. In July of 1927, Stephen and his parents had just returned from a trip to New York City where Stephen had taken two local flights over the harbor in a seaplane. Upon his return home, Steve was quite excited to discover a Curtiss biplane, a Jenny, in a field right next to his hometown. The Jenny, with pilot Ray Hylan, was ready to take up passengers.

Steve took two flights in the afternoon of July 19, 1927, in the front passenger seat of the Jenny, with Hylan, the pilot, at the controls in the rear seat. Then, after attending a twilight baseball game, Steve drove back to the "airfield" and made a deal with Hylan to go up once more. It was now dusk. News reports from the July 21, 1927 editions of the Brockport Republic Democrat and nearby Holley, New York's Holley Standard provide details on what happened next.

From the lead lines in the Republic Democrat: "A very sad accident occurred at 10 minutes after nine Tuesday evening when Stephen Peters Jr., 18-year old son of Mr. and Mrs. Stephen Peters of South Avenue, was instantly killed when the plane in which he was riding crashed into the roof of Dr. Morris Mann's house on State Street. Steve, as he is better known to his many friends, had two previous rides in the plane and was very much enthused about flying."

The Holley Standard began its story with these lines.

"In order to gratify a desire for `some extra thrills' expressed by Stephen Peters of Brockport at the beginning of a flight Tuesday night, the pilot of the plane, Roy Hylan of Rochester, attempted a tail spin which ended in a crash in which Peters lost his life and Hylan was severely injured. After leaving his landing field a half-mile east of Brockport, Hylan took his plane up gradually until he was six hundred feet above Main Street where he decided to satisfy Peters' flare for thrills by going into a tail spin."

Steve Peters was dead at the scene while Hylan was taken to the Brockport Sanitarium. When Hylan regained consciousness, he stated, according to the Holley Stamdard, that he "made a tailspin which he could not control."

The Brockport paper closed its coverage with these lines.

"Many people have remarked about the plane flying very low and the pilot was questioned about it the afternoon of the accident. Mr. Hylan claimed he always flew 500 feet or more above the ground and that that height was considered safe."

Both news sources referred to the pilot as Roy Hylan, but he later became well known in aviation circles as Ray Hylan. He operated the Hylan Flying School in Rochester for many years. In 1959, he was in the news for the donation of his Boeing F4B-4 Navy fighter to the Smithsonian Institution. Hylan died in 1983. When the Jenny crashed in Brockport, Ray Hylan was just three years older than his eighteen-year old passenger. The Brockport paper had noted, "He (Hylan) has piloted aeroplanes for the past year and was considered one of the best drivers in this section."

That accident was not an isolated experience in U.S. aviation in the 1920s. For this writer, then six years old, it was a first connection with aviation and a first connection with death. Cheap to buy as an excess WW I trainer for military pilots, the Jenny was the center of exploits in flying in the U.S. both good and bad.

Illustration 1 shows a Curtiss Jenny. It is one of the carefully restored vintage airplanes at the Curtiss Museum in Hammondsport, New York, located in the southern part of the state at the foot of Keuka Lake. This type of aircraft saw considerable service as a training plane for U.S. World War I pilots. The plane was used to carry mail in the early U.S. airmail service, and was a favorite of barnstorming pilots in the 1920s. The Jenny at the Curtiss Museum is equipped with a Curtiss ninety-horsepower OX-5 liquid cooled aircraft engine.

Illustration 1 - A Curtiss Jenny at Glenn H. Curtiss Museum

Illustration 2 -An early Curtiss Jenny aircraft, with curious bystanders, after a barnstormer landed in a Virginia farm field.

Barnstorming is a segment of flying that has no counterpart today. Russia's space program sold seat space to Dennis Tito for $20,000,000 for his rocket flight to the space station. That might herald the birth of a new era of barnstorming. With the moon and Mars on the U.S. space agenda, more self-financed astronauts may get in line. Note the drooping elevators on the tail surface.

The author's first flight; introduction to an Early Aviator and a pioneer Airport Investor

Pilots especially hearken back to their own first flight. The author's occurred, as a passenger, age 8, at Leroy, New York in the summer of 1929. The airport, way ahead of its time and a prototype for airport design, was the Donald Woodward (DW) Airport. It was named after a local aviation enthusiast who put up the money to complete an air facility in 1928, with four paved runways, hangar with corner tower, passenger ramp and space for parked aircraft. Here is an artifact from the source of Donald Woodward's success. In 1929, Woodward was President of JELL-O.

The Leroy airport was an early general aviation airport that few small cities, let alone small towns, could match. Before the airport took shape, the western New York village of Leroy was known mostly for being the home of the Jell-O manufacturing plant. The airport added to the town's prominence. Leroy was also the site of one of those early light beacon links in the visual flight navigation path spanning the United States.

My hometown, Brockport, New York, was not far from Leroy. Young boys had no difficulty claiming some of the prominence of a nearby town. This occurred most frequently when the nearby town generated some excitement. Aviation was excitement.

At the Leroy Airport, a World War I aviator, Lieutenant Commander Russell Holderman, USNR, piloted a Stinson Detroiter aircraft on a summer Sunday in 1929 in which my father, mother, sister and I were the passengers. Pilots like Holderman were the civil aviation instructors of the era, the pilots of Sunday rubberneck flights, contract pilots flying the U.S. mail and as we shall see, the first of a breed of corporate aviation pilots.

LCDR Russell Holderman, USNR, pictured in the Navy's service dress blue uniform, with his inscribed tribute to Frank Gannett, founder of Gannett Newspapers. Holderman became Gannett's chief corporate pilot early in the 1930s. It became a lifelong friendship. This photo was provided by Dixon Gannett, son of Frank Gannett, who regarded Holderman as not only the skilled, all weather pilot that he was, but also, a treasured friend of the Gannett family.

Illlustration 3 below is a photo from the published book (see top inset) that mistakenly identifies the plane in the near background as 3the Stinson Detroiter. It refers to the little single engine high wing monoplane in the mid-background of the photo. (The identification was incorrect. The plane is a Stinson gullwing design, a Reliant by Stinson identification. Go to Add-ons to the Flying Book for fuller detail of errata , credit for changes, and add-ons.) The plane in the foreground is a Boston & Maine Airways' Lockheed 10A Electra, whose instrument panel was used in the book to illustrate readiness for instrument flying, i.e. flight with no horizon. The aircraft in the illustration are on the ramp of the Boston airport, the "home port" of Boston & Maine Airways. That airline became Northeast Airlines. It expanded from its original New England region to become the last trunk airline formed in the United States. Relevant (to the published book) portions of its story can be found in Chapter 5 of the printed book.

Illustration 3- Stinson Detroiter in near background (from the book, "The Triumph of Instrument Flight.")

The photo above has been cropped to feature the Stinson. The photo appears as Illustration 2. in my book, "The Triumph of Instrument Flight." The original photo, which I had been authorized to reproduce, is in the Walker Transportation Collection of the Beverly, Massachusetts Historical Society.

I accepted the Beverly (MA) Historical Society's identification of the aircraft in the background as a Stinson Detroiter. Pilot (and reader) Mark Sellers quickly informed me that it is not a Detroiter but a Stinson Gullwing. Author , and retired Northeast Airlines/Delta pilot Robert Mudge, added the informantion that it is indeed a gullwing design, but in Stinson nomenclature, it is a Stinson Reliant. (I appreciate the corrective observations from both of these alert and knowledgable aviators. /Frank Dailey, author.)

The net result is that my book does not have a photo of the Detroiter. Now, I can partly remedy that omission in this website page. Read on.

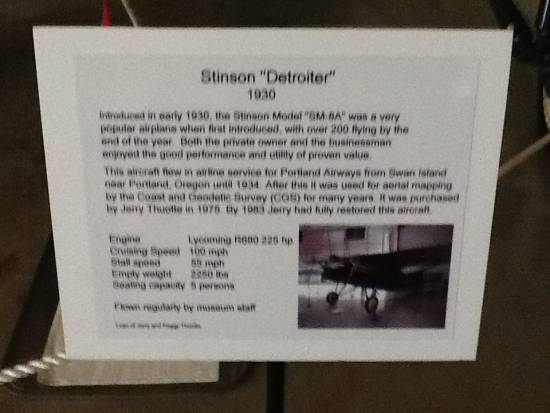

Port Townsend WA Aero Museum photos, and commentary, inserted here August 23, 2013

And now, August 23, 2013, with the help of son Philip Dailey and his wife Sally Dailey, I am able to bring the real Stinson "Detroiter" into the narrative. Their visit to the Port Townsend Aero Museum at Port Townsend, WA, on August 22, 2013, has provided a wealth of information. Their host, Gerry Thuotte, who has made this Museum a centerpiece of his working life, offered his visitors two hours of his time to give them an appreciation for aviation uniquely available from this Museum, an active working and flying Museum.

Let me first get to the aircraft in which I had my first ride. The story of how this ride came to be is related in the opening lines of my book, "TheTriumph of Instrument Flight." The missing element in that story is a photo of the aircraft in which the flight took place. So here below, from an aircraft in the inventory of the Port Townsend Aero Museum, is a Detroiter: (Let me express my appreciation to an early reader of my book, a man known as "Old Jack Reich," who first made me aware of the Port Townsend Aero Museum.)

Stinson "Detroiter" aircraft at Port Townsend WA Aero Museum

This aircraft, like all those at the Aero Museum that have been repaired/restored to flying condition, is flown from the airfield that is part of the Aero Museum's complex. I am going to assume from its markings that the aircraft was obtained from an owner in a line of owners that stem from Portland Airways, and again assume, it was Portland, Oregon. Let's see what the next plaque states. (these Aero Museum photos were taken by Philip and Sally Dailey)

Above: Detroiter plaque at the Port Townsend WA Aero Museum

(The type face on the plaque above is too small for me to read. I am 92 and WMD is creeping up. So, using a 'glass,' I interpreted

the info on the plaque and offer it below.)

Stinson "Detroiter"

Released early 1930, this Stinson Model "GM8A" was a very

popular airplane when first iintroduced with over 200 flying by the

end of the year. Both the private owner and the businessman

enjoyed the good performance and utility of proven value.

This aircraft flew in air service from Swan Island

near Portland, Oregon until 1934. After it was used for aerial mapping

by the Coast and Geodetic Survey (CGS) for many years.

It was purchased by Jerry Thuotte in 1975. By 1984 Jerry had fully restored this aircraft.

Engine by Lycoming 225 hp.

Cruising Speed 100 mph.

Stall Speed 55 mph.

Empty Weight 2250 lbs.

Seating Capacity 5 persons.

Flown regularly by qualified staff.

Note" The bottom line here on this important plaque is too small for me to decipher. Also, a "Detroiter" is the photo inserted in the plaque. There may be other mistakes in my reading of this informative plaque. But, I did guess right on the early life of this aircraft. /Franklyn E. Dailey Jr./

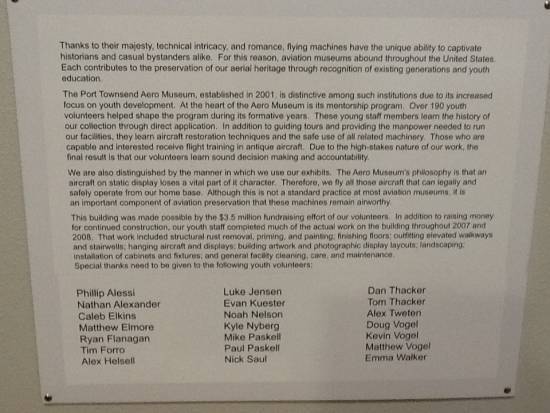

A Founder plaque at the Port Townsend WA Aero Museum

End of mateiial inserted August 23, 2013 based on a visit to the Port Townsend WA Aero Museum

Further comment on Stinson aircraft:

Eddie Stinson, and the Stinson family, located in Detroit, Michigan, designed and produced a number of fine aircraft. The Detroiter was one of them. Later came the single engine Reliant series. The plane in the photo on my instrument flying book's cover, is a Stinson Trimotor. This Trimotor was a high wing machine, the first of two Trimotors that Stinson designed and built. That first Trmotor is on the cover of "The Triumph of Instrument Flight" because I learned that the pilot shown, Hazen Bean, had used the new 'turn and bank' instrument on its pilot instrument panel to fly straight ahead, wings level, while he piloted his passengers up to a clearing in the solid clouds he had encountered on a takeoff from Boston airport, and to safety. That aircraft did not have gyro horizon or directional gyro instruments. And its first gyro instrument, first-named 'turn and bank,' was actually misnamed in my opinion. Bean had a lot to overcome, and Robert Mudge in his book "Adventures of a Yellowbird," put me onto this incredible experience. (And, many more.).

The Stinson Detroiter at Leroy in 1930 (my book states 1929, but the Aero Museum's data had 1930 as its introductory year) had a glass panel in the bottom of its small cabin through which the three passengers in the rear could look straight down. This was an opportunity my Dad exercised just once during that flight, pleading later that he did not like the 'feeling' it gave him.

The right front seat of the Stinson "Detroiter" was mine for this, my first, flight. It did not permit the downward vertical look. But, through my window on the right side forward, I could see Niagara Falls! As flights go, it was just a 20-minute tour of western New York State. My father paid 30 dollars to a ticket agent near the plane. My younger sister and I went for $5 each and the adults had to pay $10 each.

I do not believe Dad ever flew again. Near Huntsville, Ontario, we vacationed for short periods in two summers at a resort named Limberlost. The resort was on one of those countless, see-to-the-bottom, lakes of Canada. Mother took many rear cockpit flights there in a single engine biplane, pontoon equipped. The aircraft was a DH (de Havilland) Moth, and it was piloted by a Major Wrathall in Canada's Air Force.

Let me close this Stinson discussion with an artifact created by the talented Bill Benton of Batavia, New York. Bill , among his other credits, is a craftsman, and chose to remember Stinson with this light metal rendition of the Stinson logo.

A Stinson logo, executed in light metal by Bill Benton of Batavia New York

Russell Holderman, Early Aviator, Airport Manager, Stinson "rep," and then Chief Pilot, Gannett Newspapers Co.

You have already seen his photo earlier on this page. Russell Holderman, Lieutenant Commander USNR, piloted the Stinson Detroiter for my first flight, at D. W. Woodward Airport in Leroy, NY. I was nine, my Sis was eight, and Dad and Mom came along for the flight. My lifelong belief was that it was in the summer of 1929 but Gerry Thuotte's history; above, indicates it must have been 1930.

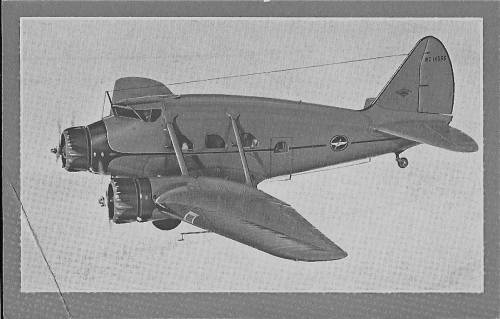

I did not know it at the time of our first meeting but Russell Holderman was also the Donald Woodward Airport's Manager and had a hand in the airport's design. Russell Holderman later became the Gannett Newspapers' chief pilot, for much of that extensive tenure, in command of a coveted Lockheed Lodestar. About 30 years after that 1929 (~ 1930) flight, I had left active duty as a Navy pilot and transferred to the Naval Air Reserve. My father invited me for lunch at the Rochester Club on East Avenue in Rochester, New York. Dad was a stockbroker and occasionally took clients to the Club. This day, my Dad had an ulterior motive. He introduced me to Lieutenant Commander Holderman, who, I learned, was a regular at the Club, with his own accustomed luncheon table.

The Gannett Newspapers' Lodestar, with its experienced, instrument qualified pilot, was a major help in newspaper owner Frank Gannett's effort to build a national newspaper empire from a two-newspaper base in Rochester, New York. The print flagship of that news organization is USA Today. So much for my original knowledge of Russell Holderman and the inferences I made from brief glimpses into his record. Let me introduce Dixon Gannett, son of Frank Gannett, the man who made major news himself in the news business.

At the outset of our e-mail correspondence, Dixon informed me that Gannett owned a string of fine aircraft, the last one being a Martin 404, and Holderman flew them all. We will find in some of the following paragraphs much about the unique relationship that existed between Frank Gannett, Publisher, and his Chief Pilot, Russell Holderman. One facet is that in taking the new job, Holderman negotiated with Mr. Gannett to keep his 'rep' role for Stinson. So here is an early plane in the life cycle of planes that Frank Gannett purchased or leased to 'get around' the USA.

Illustration 4- A Stinson Tri-motor

Note: This is obviously not the Stinson Tri-motor found on the cover of my book (photo at top of this page). That Tri-motor is a high wing plane and was key to the early success of Boston and Maine Airways. The Stinson above was flown in commercial service by American Airlines and Pan American Airways. Author Paul Moxin, in his book, "One Foot on the Ground," identifies one of these as a Stinson Model 'A' flown by American.

The italicized paras below are Dixon Gannett's note to me, stimulated by my original comments on Russell Holderman:

In searching for information about my dear friend, Russell Holderman, I ran across an article on the internet at www.daileyint.com/flying/flywar0.htm . Let me add some background on this early aviator that even students of the early aviation subject are not likely to know.

Russ was, as was stated in the article, instrumental in the layout of the LeRoy airport, I guess, in the 1920's. My father, Frank Gannett, wanted to charter an airplane one day, and contacted Russ in LeRoy. Russ at that time had the franchise for Stinson. Dad was highly pleased with pilot Holderman, and was interested in hiring a pilot for the Gannett Company. Russ agreed, with one stipulation; that he be allowed to continue his operation as a Stinson representative.

So, Russ Holderman set up an office at the Rochester airport to sell Stinsons as well as being chief pilot for Gannett. Russ and Dot Holderman bought a house next to the Country Club of Rochester where they lived for many years. I was a constant visitor. Russ even landed the Stinson Reliant on the golf course behind his house.

As the years passed, I remember many different airplanes owned by Gannett Co. There were two Stinsons (an old yellow or light colored high wing circa 1938, a Reliant gull wing circa 1941), a Navion single engine, a low wing Sparton (others at that time I can't remember), a Lockheed 10, 12, then an Air Force retired Lockheed Lodestar. Oh yes, there was the Stinson Trimotor. (My sister said that the smell of fuel from the nose engine made her sick.) I remember the Reliant well. The side of the airplane by the rear seat, on the left side, could open up to allow a photographer to take pictures without looking through a window.

We made many trips from Rochester to Miami in those early years. Twelve thousand feet up in the Reliant was quite a trip. Russ would often run the fuel out of one tank to the point that the engine would die. With the nose down slightly Russ would just switch tanks and the engine would prime itself, and away we would go again. Of course, there was the old New York to Miami race years ago. Dad let Russ alter the fuel tanks by putting one in the radio area of the Lockheed. Russ lost the race by thirty seconds. Who beat him? A pilot with a staggered wing Beechcraft, with a navy fighter engine. During the flight, a valve in the engine got stuck. The pilot switched the engine off and glided for some time allowing the engine to cool. He then restarted the engine to full throttle which broke the valve loose. 30 SECONDS!

I remember during WW 11, during one of our trips to Miami in the Lockheed (I don't remember which one); we were flying at about 12,000 feet over Florida when a navy trainer (twin Beech) flew along with us about a mile away. The bomb bay doors opened up and a bomb dropped toward a target in a lake down below.

Yes, Russ set many records - such as the loop-the-loop. He told me 50 consecutive loops without a single break for speed or to gain altitude. Then there were the one wheel touch downs during air shows which pleased the crowds. In one race, his engine exploded as he streaked toward the enthusiastic crowd. He landed safely in a field but behind a wooded area where the people couldn't see him. Rescuers ran to his aid only to find him leaning calmly against his undamaged aircraft - except for the exploded engine. I remember seeing a piston and connecting rod in his basement sitting room, the rod bent double. Russ had picked it up in the field as a souvenir.

One day in Albany, N.Y. Russ was flying a float plane. Dot Holderman was with him. Suddenly the engine quit, spraying oil on the exhaust which created some black smoke which was easily seen from the city. Russ and Dot exited the plane into a boat. Of course, the local paper reported that the two had exited their "burning" airplane.

Russ would never own up to it, but he pulled a good "stunt" in the New York to Miami race. It was highly covered by the media. Dot had hidden in the lavatory of the Lockheed before the race, then exited the plane in Miami, everyone thinking that there had been no passengers. Of course, the media had a field day reporting that Mrs.Holderman had been a stowaway.

Let's not forget Dot Holderman, who set records for women in her own right. One was the endurance record of over five hours - in a glider. Remember this one fact - DOT HATED TO FLY! She was a real "white knuckle" flyer as I recall on one flight south of Rochester during a bumpy trip. Russ was pilot, of course.

Over the many years, I tried my best to get Russ to write down his many experiences during his 50,000 hours of flight time; his being president of the Early Birds Club (having soloed in 1913); the many aircraft he had flown - from the 1913 plane where he sat out front in a seat open to the wind to the large B-29, etc.; the places he had flown to and even the famous and fabulous people he met, even how he had obtained the wicker chair in his basement that Amelia Airhart sat in, during her trip across the Atlantic as a passenger and first woman to do so.

Every once in awhile one runs across a person cut way above the rest, and Russ Holderman was certainly one of those. Though he had never been injured in an airplane, one wonders why he had never been hurt as he drove at high speeds around town in his Cadillac, blowing his horn constantly to move people out of his way - or was it "look out, here I come!"

I am sure there are many other stories about Russ Holderman in the minds of his relatives, friends and business associates. I know of just a few - some I am sure have been forgotten. Maybe I will remember them and add them to my list. Who knows. I know this for sure - Russ was a true and real pioneer. It was a privilege to have known him. And many of aviation's heroes and pioneers knew him as well.

/s/ Dixon Gannett Oct. 2010

Here are some three 'looks' at Lodestars, supplied by Dixon Gannett; first, one with Wright R-1820 engines

This next one has P&W R-1830 engines; in civil aviation this was the predominant choice

Here is a Lodestar in the U.S. Army's olive drab

Illustration 5- Set of three Lockheed Lodestars

The Lockheed Lodestar was fully configured for instrument flight, and could handle rough weather. Both my wife Peggy and I flew as passengers of National Airlines, me from Miami to Key West and Peg from Norfolk to La Guardia. Variations of this basic airframe earned fame as Lockheed Hudsons in the British Coastal Command intercepting U-boats entering and leaving the Bay of Biscay in World War II. Memories can be deceiving but I seem to recall that the famed Fowler Flaps were a feature of this model. Can anyone confirm or deny?

Some Added Thoughts

At Leroy on that summer Sunday in 1929 (I now believe it was 1930, basied on Holderman's notes on the arrival of the first Stnson 'Detroiter ' at DW Woodward Airport at Leroy NY-FEDJr 11/22/13), there were other aircraft parked at the airport. Most were the single engine biplanes of early aviation. A few of the aircraft parked at Leroy that summer were single engine, high wing monoplanes. All were painted orange. I was told that the plane type was a Curtiss Robin.

Pilots and mechanics based at Leroy were themselves recognized, by better known aviation peers, as key contributors in aviation's early years. For that reason, when Donald Woodward's airport at Leroy held fly-in events, it attracted many well-known national and international figures, all pioneers in early aviation.

With the entrepreneurial investment of Woodward, and the pioneering pilots that his foresight attracted, the town of Leroy was early on aviation's map. In just a few years after 1929, larger U.S. cities became the essential airline embarking and debarking points for the growing number of paying passengers. As the pilot proficiency base grew and radio aids were installed across the United States, the introduction of radio receiving instruments became a requirement for commercial aircraft. The tools for instrument flying were falling into place. Scheduled flights with paying passengers multiplied. Towns like Leroy drifted into history. California, Texas and Illinois became leaders in the number of aviation early adopters. Distance was a spur to flying.

Many pilots, like Russell Holderman, moved on to salary-producing aviation careers. The barn-storming pilots elected to make their living in more of a free form that perhaps identified them more as lovers of flight for the sake of flight and not as just an alternate means of transportation. Even the famed Charles Lindbergh did time as a barnstormer.

Every time an airplane went overhead in the early years of flight, persons of all ages turned their eyes skyward. Most vivid is my memory of the giant Navy dirigible, the USS Akron, passing over my home in western New York in 1931 on November 11, Armistice Day. She was creeping along under a very low overcast in restricted visibility, trying to stay in visual contact with ground reference points on the south side of Lake Ontario as she made her way back from a western trip to her home port of Lakehurst, New Jersey.

That dim gray wraith that took up so much space in the moisture laden sky was a discussion topic for folks in our town for months afterward. I can make a pretty good conjecture now that the Akron's Commanding Officer that day did not feel that his dirigible, his flight instrumentation, and he, were capable of simply plunging into the clouds and heading directly for Lakehurst. Visible checkpoints like nearby Rochester on the south shore of Lake Ontario were the navigation aids he trusted.

A man-made connection existed between two U.S. dirigibles and heavier than air flight. The Akron and her sister ship, the USS Macon, were both rigged with a hangar and suspension for a small aircraft. A number of aircraft flights from the two dirigibles and airborne recoveries to them were made successfully. Both dirigibles met their ends in separate crashes that involved fatalities. These crashes had nothing to do with their embarked aircraft.

Today (2004), I see giant C-5 jet transport planes taking off from or approaching Westover Air Reserve Base (ARB) in Chicopee, Massachusetts. I hear sleek Boeing and Douglas jet transports shushing overhead toward Bradley International Airport at Hartford, Connecticut, as they pass down the instrument runway approach path directly over my home. When I am out in my neighborhood, I always turn my head skyward on the chance that the approaching aircraft will "break contact" as it emerges from clouds.

Franklyn E. Dailey, Jr. June 3, 2004 (updated October 31, 2010, March 2, 2011, and March 29, 2012)

For a different perspective with some of the same aircraft players on this website go to Boston &Maine Airways' early success began with Stinson Trimotors, then Lockheed 10 & 12 Electras. It renewed its competitive vigor by renaming itself Northeast Airlines, the last trunk line to be authorized in the U.S. It was then bought by Delta.

Copyright 2013

Home | Joining the War at Sea | The Triumph of Instrument Flight