The new Fourth Edition

with 44-page Index

Joining the War at Sea 1939-1945

- Draftees or Volunteers

- U.S. Military Draft and Pearl Harbor

- Warship Building

- World War 2 U-Boat

- Collision at Sea

- Operation Torch

- Sea-based SG Radar

- Attack Transports Sink

- Assault Landing

- Tiger Tank

- Darby Rangers Setback

- Eisenhower Needed Seaports

- Rohna Sinks; 1000 Soldiers Perish

- Death, Survival, and Leyte Gulf

- Annunciator Speaks!

- World War II Sinking

- British Rescue Ship Toward Sunk

- Self Inflicted Wounds

- No Abandon Ship for USS Ingraham

- Rohna Tragedy Tops Transport, Destroyer Toll

- Four Chaplains

- U-73 speaks from the depths

300 warships and transports in "Joining the War at Sea" listed alphabetically

Transports Chatham, Mallory, and Dorchester with Four Chaplains, sunk

Chatham survivors speak. St. Anthony, Newfoundland honors the dead

Copyright 2014 Franklyn E. Dailey Jr.

The sinkings of transports Chatham, Dorchester, and Mallory in cold North Atlantic waters in late 1942 and early 1943 are covered on pages 59-62 of the Fourth Edition of "Joining the War at Sea 1939-1945." ISBN is 0966625153. The new Henshaw Index of over 300 ships in this book is available for download from these pages. Also, much of this material became available after, and because of, the printing of the book. Purchasers of "Joining theWar at Sea 1939-1945" are invited to print out as much of this extra material as they might wish to have to go with their book.

What follows here are five remembrances of the sinking of Chatham; one of these has an important observation about Dorchester and launch of lifeboats after being torpedoed. Illustrations on web pages require extra vertical spacing. This may leave white space. Keep scrolling down to make sure you have seen all of these remembrances.

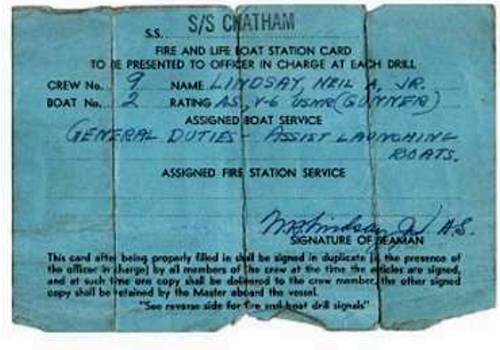

First, pictured next, are two fragments of torn but but readable fire and lifeboat station cards,.The 1st (blue) fragment is a life boat assignment to Neil A. Lindsay Jr. on SS Chatham. This is followed by a portion (2nd blue fragment) of Chatham's fire and life boat drill signals. When sunk, this ship was the U.S. Army Transport (U.S.A.T.) Chatham. There was no time during World War II to change all instructions and markings on hastily commissioned transports pressed into war duty from merchant ship service, in this instance, the SS Chatham. The pictured fragments below were sent to me by Neil Lindsay, son of the man who sailed as member of the Armed Guard on Chatham in August 1942. The Neil Lindsay on Chatham was assigned, "General Duties - Assist Launching Lifeboats." When one pictures the actions required of those words, the words take on special meaning when reading the fourth remembrance that follows later on this page from Donna Cuzze.

Immediately following are pictured fragments brought home from the war by Neil Lindsay, is a comment from his son, Neill Lindsay. Please keep scrolling down to continue this story.

"Fire and Lifeboat Station Card" from lifeboat launched from USAT Chatham after U-boat torpedoing.

"Fire and Lifeboat Drills Signals" from torpedoed USAT Chatham

"My father (Neil Lindsay) always talked about this sinking (SS Chatham) as if it was a very personal thing because he got married 12/26/1941 and the next year his ship sank-he was with the Naval Armed Guard-he enlisted right after Pearl Harbor at Charleston; this sinking was on my mothers birthday which was August 27 and being newly married I guess he thought a lot about not being at home but he always said he prayed to God to please let him come home and we (his bride and himself) would attend the Baptist Church just one time because he was married at my mothers home in Fayetteville not in the (Baptist) Church because the Baptists in our area in the 1930's would not allow any one else that was not Baptist to take communion in the church-he was Presbyterian and he said he would not go to a Baptist Church. My mother was raised a Baptist -when he was in the water in the North Atlantic at that time he prayed to just get home and he would go to the Baptist Church with my mother for answering his prayers.

He was later a Gunnery Officer on the SS Cape Alexander during the Okinawa campaign. Thank God we have had the experience to know these folks; they have helped our country be what it is today. Thank you."

/s/ Neill Lindsay, Fayetteville NC 08/14/2007; Neill is the son of Neil Lindsay who served in the Naval Armed Guard in World War II.

Second, an official report, in two pages, that Neil Lindsay, by this time CO of another Armed Guard unit in the Pacific, was required to make in 1945. Again, the author of the book, "Joining the War at Sea 1939-1945," is indebted to Neill Lindsay, the son of the Chatham survivor whose artifacts are reproduced in this web page.

.

.

Third On May 9, 2008, Barrett Swink of Annandale,Virginia, forwarded this remarkable photo of some of the survivors of USAT Chatham. The photo was taken two days after the sinking. Leonard Anderson, Barrett Swink's wife's Uncle, is seated in the front row, fifth from the left, with a faint X just below.

Fourth Side by side graves in a churchyard in Newfoundland mark the burial sites of two Chatham men who were found in the waters off the coast a few days after Chatham was sunk. This information was received on Saturday morning, November 27, 2010, first in a phone call from Newfoundland, and then in a follow-up e-mail on Saturday afternoon. The originator is Francis Patey, a native of Newfoundland. The graves are unmarked but visible, and if we can determine the identities of the two men, the graves will be marked. Read and you may be able to help. The following is the transcript of Francis Patey's followup e-mail to his phone call to Franklyn E. Dailey Jr. on the morning of Nov. 27, 2010, 68 years and 3 months after the sinking of the transport U.S.A.T. Chatham, originally SS Chatham.:

Re our telephone conversation todays' date, re-the sinking of the ss chatham, in the strait of belle isle, newfoundland and labrador. by the u-boat 517 on august 27, 1942. Belle Isle, where the sinking took place is approx. 30 miles from the town of St. Anthony, my home town. Many of the older residents can recall watching the fire power from their homes, during the battle of the atlantic. 13 people died in the sinking of the chatham. On September 2, 6 days after the sinking, two local fishermen picked up two bodies floating near their community, both wearing Chatham life jackets; on september 4, both sea men were buried in the United Church cemetery on Fishing Point in the town of St. Anthony, by Rev. G.R. Cooper. I have in my possession a snap shot of the funeral, two caskets, one a large white one, the other a smaller black one, with about thirty local people standing beside the open graves which are still visible. A description of both men were recorded in the United Church diary. Number one: wearing blue jeans blue shirt, grey stockings, tan shoes, and around the neck a blue cloth, height 5 feet 6 inches,weight 140 pounds, blue eyes ,bald on top of head, hair around back of head dark brown, approx. age 40 to 50 years. Number two: second body, wearing khaki shirt and pants ,brown socks, black shoes, in pocket a wrist watch and a bunch of keys, on finger on left hand were two rings one with the initial ELP, the other a blue stone; body was 6 foot 1 inch weight, 200 pounds ,black hair, two rows of natural teeth, complexion dark, age probably in the twenties. Both graves are still visible. On the internet a ms. donna cuzze (see below) writes about her father, Neil Lindsay, talks about the sinking of the Chatham, so maybe some one can shed some light on who these two sailors are and give them a marker. Regards /Francis Patey/, St. Anthony, Newfoundland Canada.

Fifth, another remembrance of Chatham, again from a survivor of her sinking. The speculation on Dorchester is particularly interesting.

THOMAS POWELL COOPER, U.S. Merchant Marine

Survivor of the U-boat sinking in WW II of the U.S. Army Transport -U.S.A.T. Chatham (in peacetime, SS Chatham). His idea, based on first hand knowledge of the sinking of transports Chatham and Dorchester, is presented by his neice, Donna Cuzze.

Hello!

My name is Donna Cuzze. While doing family research, I asked my mom, Mrs. Dorothy Carpenter, about her uncle, Thomas Powell COOPER. She said he was born Mar 21, 1904 in Talladega County, ALA. He had two sons. One was named Billy.

Thomas Cooper joined the Merchant Marine when he was seventeen years old. His sisters were Mrs. Florence Bramlett (my mom's mother) and Ms. Josephine Cooper. Uncle Powell referred to them as Tiny and Jo. I can remember the beautiful stamps from all over the world that came on the letters and postcards that Uncle Powell mailed to them. Only a few of the postcards have remained since his death August 1, 1970 in Astoria, New York. His sisters have also passed away.

Mom dug out an old article for me that was published in the National Maritime Union newspaper. It appears to have been published after my Uncle's last voyage on the Silver Mariner which was launched in 1954. On the backside of the article is a shipping report for November but the year is cut off. In the notice section is an inquiry for someone holding a receipt dated July 17, 1956. So, the article was published sometime after that and shows part of another article in which Joseph Curran was still NMU president.

The article was about Uncle Powell's invention for safer lifeboat launches from sinking ships. He was first motivated while floating for a day, in an open life boat, in the icy seas, awaiting help after his ship the SS Chatham went down off Labrador in August 1942. My mother remembers the family talking about this invention. In particular, she remembers her Uncle Powell saying lifeboats work on gravity but there is a better way.

This article includes a photo of my uncle pointing at a blueprint and a caption, "Tom Cooper explains his lifeboat invention." Here is the headline and the text of the article in a late 1956 issue of NMU News:

"NMU Idea Man Invents Better Lifeboats"

"Thomas Powell Cooper is a man with a mission. His purpose is to help cut the toll of lives in marine disasters. He has the answers, he says, in blue-prints for new types of life-saving equipment. His problem now is to get his ideas put to use.

A new kind of lifeboat which he describes as "a radical departure from the conventional" is Cooper's main project. His boat will be launched by a method which does not depend on gravity and, he claims, it will make obsolete the davits now in use. This is not at all Cooper has to offer. In the course of working on his prime objective of developing better life-saving equipment for ships, Cooper has come up with a wide range of ideas including safety devices for planes and subways, new weapons and defenses against weapons, new insecticides and even that "better mousetrap." It is his hope that at least one of this assortment will provide him with the money he needs to patent and promote his lifeboat and other shipboard inventions. Cooper admits that little in his training or experience was designed particularly to equip him for the mission he has set for himself. He has been going to sea for the last seventeen years, shipping mainly in the steward's department. In earlier years he did some professional boxing. He worked for a while with the Army Engineers in Hawaii and the Aleutians in a non-technical capacity. He went to agricultural college for a couple of years, with drainage pipelines as his major subjects. Cooper believes that the seeds of his inspiration were planted by two war-time torpedoings, the SS Chatham off Labrador in August, 1942, and the SS Dorchester in the same area some months later. He was one of the few survivors of the Chatham sinking. He wound up in the hospital with a spasmodic stomach condition which got its start during his day in an open boat in sub-freezing temperatures after the sinking. He was laid up for several months and lost nearly a hundred pounds. In that time he did a lot of thinking about how many men escape the seas when their ships go down in Arctic waters only to fall victim to the temperatures. Cooper was not in the Dorchester disaster, but he was close to it. He had been aboard her when she was brought into New York prior to taking off on her final voyage. He knew most of the crew which was aboard when she went down. Some of these were among the handful of survivors, and from them he got first-hand accounts of the tragedy. [What impressed him particularly was the grim fact that hundreds of men who had gotten safely away from the ship in lifeboats were frozen to death before dawn.] This got him thinking again about what could be done to give men a fighting chance when their ship went down in Arctic waters. The lifeboat was the first idea to be put down in blueprints. It was designed first to meet needs in Arctic temperatures, Cooper explains; but in any kind of waters "it surpasses in safety, comfort and protection of the occupants anything now in existence." The idea for the mousetrap came to him during his last voyage aboard the Silver Mariner. It is a very simple device which can be mass-produced to sell at a very low price, he says. It is the lifeboat that Cooper is putting most of his efforts to. He has been making his pitch on this to some high-placed government officials, naval architects, engineers and industrialists. He has received varying degrees of encouragement, but none of the solid assistance he needs. "Money is the main problem," he explains. "I need a patent and I need a working model, and these things need money." Cooper isn't discouraged, though. With a backing of firm faith and determination, he intends to keep trying. "I'm trying to save thousands of lives," he points out. "If all my effort results in saving just one of the lives that are now needlessly lost at sea, it will all be worthwhile."

/s/ Donna Cuzze, June 14, 2003

Author Franklyn E. Dailey Jr. comments: :Thomas Cooper had a worthy objective. Trying to get boats lowered after a torpedoing led to: (1) lifeboats on low side capsizing immediately because ship was already listed too far (2) lifeboats falling back onto the deck, for the same reason, applied to boats on the high side of the listing ship (3) and for boats hanging from a ship going down by the bow or stern, a lifeboat hanging by one davit after the falls slacked or snapped on the other davit, throwing occupants into the water. For those interested in going to the NMU archives for an article cited by Donna Cuzze, my (author Dailey's) guess on publication date would be late 1956. I have studied carefully the NMU News article covering Tom Cooper's idea that gravity was not the best way to launch lifeboats. I believe the editor failed to capture the essence of Tom's motivation in one crucial sentence. Remember, Tom almost froze overnight in his lifeboat after the Chatham sank. Tom was impressed with his own survival. He was tuned to the consequences particularly because he survived the Chatham sinking, and because he had personal friends on the Dorchester. Tom was aware in 1943 of the terrible loss of life because so many of the Dorchester men were in the water. Tom Cooper's objective was to increase the success rate in launching lifeboats and keep more of the immediately surviving personnel alive by giving them a lifeboat chance to live. I have taken the liberty of putting brackets on the following sentence in the NMU News article which reads: [What impressed him particularly was the grim fact that hundreds of men who had gotten safely away from the ship in lifeboats were frozen to death before dawn.] I think the editor and Tom failed to communicate when that sentence was written. Tom surely did not have the chance as an author to proof the sentence. I believe that sentence should not have included the phrase, "in lifeboats." Tom did watch some men freeze in lifeboats and get permanent injury from frostbite. But they, and he, survived. But, the entire thrust of his idea was to have lifeboats successfully launched in order to give more men the opportunity to be in a lifeboat, and not in the water, where they would surely freeze to death in minutes, not in hours! The last four paragraphs of the NMU News article emphasize lifeboats. It is the lifeboat, the successful launch of the lifeboat, that will save lives. It is the lifeboats that did not get launched from the Dorchester that caused so much loss of life. Dorchester was as much a part of Tom Cooper's motivation as Chatham. Chatham taught him, Dorchester convinced him.

We add yet another visit from the SS Chatham. 03/08/2014 The visitor who found this page is Joe Paul whose father Joe Paul was on the last lifeboat to push off before Chatham sank. Joe the son reports that his Dad left with the Chatham's skipper and the O-in-C of the ship's Armed Guard unit. Joe Paul the father is not in the group photo shown above, having been picked up by a Canadian corvette and landed at Goose Bay Labrador. Joe Paul lived briefly with a family named Slater there .

Here is a chart from my book "The Triumph of Instrument Flight," which is

used in that book because it showed the routes the U.S. and Canadian planes

took to ferry aircraft and supplies to the Biitish

Isles.

Remember that transports Mallory, Chatham and Dorchester were lost , in separate and tragic events, attempting passage to Greelnland by hugging the coastal arc of the North Atlantic. That proved to be bad sea strategy and the U-boats loved the vulnarable targets.

In the Fourth Edition, no material has been removed from the earlier editions but prewar pages have been condensed and inserted in the back of the book so that WW I I action begins sooner in the new edition, ISBN 0966625153. Now in 6x9 format with new covers and photos improved. For those who have purchased any published edition, a download of this material is authorized.

Home | Joining The War At Sea | Triumph of Instrument Flight