The new Fourth Edition with 44-page Index

Joining the War at Sea 1939-1945

- Draftees or Volunteers

- U.S. Military Draft and Pearl Harbor

- Warship Building

- World War 2 U-Boat

- Collision at Sea

- Operation Torch

- Sea-based SG Radar

- Attack Transports Sink

- Assault Landing

- Tiger Tank

- Darby Rangers Setback

- Eisenhower Needed Seaports

- Rohna Sinks; 1000 Soldiers Perish

- Death, Survival, and Leyte Gulf

British Rescue Ship Toward Sunk

No Abandon Ship for USS Ingraham

Rohna Tragedy Tops Transport, Destroyer Toll

300 warships/transports in "Joining the War at Sea" listed alphabetically

Convoy AT-20: USS Ingraham DD-444 sinks; Buck DD-420, oiler USS Chemung damaged. SS Awatea , disappears. August 22, 1942 off Halifax.

USS Bristol DD-453, is torpedoed in the Mediterranean; analysis by BuShips, using survivor accounts. Midway down on this page. Bristol had done valorous rescue work in Convoy AT-20 and helped save survivors of the USS Rowan at Salerno.

Copyright 2012 Franklyn E. Dailey Jr.

Convoy AT-20 was a heavily guarded all-troop convoy that left Halifax on

August 22,1942, bound for the port of Glasgow Scotland. The entire DesRon

13, nine modern U.S. destroyers, was assigned to escort troops needed for

the defense of Britain, through U-boat infested waters. A U.S. cruiser and

a U.S. battleship was assigned in the event that Hitler ordered

Scharnhorst or Tirpitz to intercept.

The reader of the published book,"Joining The War At Sea 1939-1945" can learn in much greater detail of the terrible events that befell Convoy AT-20 on its first day out of Halifax N.S. in dense fog, especially in the convoy's first night at sea August 22, 1942 in dense patches of fog. That event left the USS Ingraham DD-444 on the bottom of the sea, the USS Buck DD420 without her stern and her two screws, the tanker USS Chemung afire in her bos'n stores forward, and the troopship, SS Awatea, with 5000 Canadian Troopers aboard, nowhere to be found. In 1997, I received e-mail feedback sent by Stewart Valcour shortly after he received a copy of the first edition of the book. Valcour was the son of a Canadian trooper who was embarked on the Awatea that evening . Valcour, the trooper was still living in 1997. That trooper was able to inform me through his son that the Awatea limped back toward Halifax on her own with a badly damaged bow. That Canadian trooper's feedback came as the result of putting the draft version of the book on this website. The trooper's feedback was then incorporated in the published book in the fall of 1998. The balance of the interpretation as to what happened, still lacking a full understanding of why it happened, was my own. In brief, I believed then that the Buck's stern had been sliced by the Awatea, and that the Chemung's bow had ripped into the belly of the Ingraham. The Ingraham exploded and sank rapidly and the Chemung was left on fire forward. In clearing fog, the Chemung was found by my ship, the USS Edison, DD439, many miles from the Buck. There had been no fire on the Buck. The Buck had lost freeboard aft due to stern flooding. Crewmembers trapped in her after steering engineroom were lost when her stern dropped off as the USS Buck tried to turn over the one screw that had not been lost in her initial collision with the Awatea.

I will shortly introduce another Canadian trooper's comments about that evening's events. His account, like all prior accounts including my own, will still be missing answers to the "why" question. As noted in the book, Ensign Melvin Brown USN was the only officer survivor of the Ingraham. He was a Naval Academy classmate of mine (USNA Class of 1943, the first wartime class to graduate a full year early in June 1942) and we had just graduated from the Academy two months earlier (June 19, 1942). As I developed a plan to interview Mel Brown in 1997, I was informed of his death when I received the next issue of Shipmate, the Naval Academy Alumni Magazine.

Any Ingraham survivor's story would help establish the facts, especially if he had been on duty around the bridge. When Ingraham was ordered to investigate a 'collision in the convoy' (that of Awatea and USS Buck) I assumed that Ensign Brown reported to his Mk. 37 Director station for Condition II,.There were just 10 other survivors. I have also made some attempts to find persons still living from the USS Philadelphia. Some member of that ship's company might be able to provide information about the specifics of Task Force Commander Rear Admiral Lyal Davidson's commands, first to the Buck, and then to the Ingraham to "close the convoy." Buck's orders were to coach a transport (SS Letitia) to the specified convoy course and Ingraham's orders were to close the convoy and investigate a "collision", which collision presumably involved the Buck.

The Buck was logically chosen to give Letitia the correct convoy base course, having the screen commander (ComDesRon 13, Captain John Heffernan USN) embarked and having a more roving position assignment in the screen and not responsible for a fixed ASW defense sector. The Ingraham was then a next logical choice to investigate a collision in the convoey, having the aft sector on the same port side of the convoy from which the Buck had attempted to enter the convoy. In that most dense of all fogs, with no tool like SG radar for finding any ship, and with all convoy ships strictly on helmsman stationkeeping, using the towing spar of the convoy ship in column ahead as the only course and speed guide, it was foolhardy for any screen ship to attempt to enter convoy lanes. The only potentially successful approach would have to have been from astern of the convoy after asking the row of stern ships of that convoy to also stream towing spars.

My first informant that evening in dense patches of fog, was Ensign Richard Hofer USN, just one class and 6 months ahead of me out of Annapolis, who I was relieving that evening as Junior Officer of the Deck Underway. On the port wing of the Edison, Dick and I together witnessed the most blinding flash of light ever to penetrate a thick fog. He then told me that the Ingraham had earlier been told to "close the convoy at high speed." Dick was one of the coolest and most capable officers I encountered in that wartime period. He was not given to exaggeration. He did not relate to me the 'tone' of voice that he heard over the TBS giving that order. Often we could tell when the Convoy or Task Force Commander personally gave the TBS order. But Dick gave me no more than the words themselves. (Dick became a Navy pilot and was lost in an aircraft crash not long after WW II.) The cruiser Philadelphia, on which Admiral Davidson was embarked, and the battleship USS New York, were with Convoy AT-20 as Ocean Escorts, to defend against any major German cruiser or battleship that might attempt to interfere with AT-20's transit to Scotland. The Philadelphia was often chosen to be Admiral Davidson's flagship and she and he acquitted themselves heroically in later months in the battle to beat back the Nazi forces in the Mediterranean. A first hand account from the bridge of the Philadelphia for that evening of August 22, 1942 would be a required assignment for historians. But, lacking that, let me go on to the account of William Brown, another Canadian trooper aboard the Awatea that evening.

In the next paragraph, I will quote verbatim Trooper Brown's first e-mail to Richard Angelini, webmaster for the Benson/Livermore destroyers of World War II. That e-mail was dated July 12, 2000. When big ships collide, whatever motion state they are in at the time of collision continues in spite of orders to the engineroom. Observations covering seconds would see those ships transversing ship lengths and one minute could easily mean a distance in which fog would change sharp outlines to a hazy apparition at best to total disappearance. Let me put this into numbers. These convoys made about 15 knots. Let me arbitrarily make that 15 miles per hour, a little under 15 knots. Fifteen miles per hour is 22 feet per second. In one minute a convoy ship would travel over 1200 feet, at least two ship lengths. A collision with a destroyer would hardly slow a liner like the Awatea. The convoy ships could not see the ship ahead due to fog. A towing spar three hundred feet behind would put those ships in column only 15 seconds apart, very little margin and an important marker not only for course and speed but for measurement of visibility.

William J. Brown: His first e-mail

"My name is William J. Brown. I was a trooper in the Canadian 4th Division during ww2. I was on the Canadian troop ship (a converted passenger liner) that collided with the USS Ingraham. It was not an oil tanker. I saw the collision. I was just going up for watch on the bridge at midnight. As I was going up the stairs I felt a tremendous jolt and all glass shattered. Since it had been a passenger liner, there were lots of mirrors and glass...it had been commandeered for troop movement.

I cannot recall the name of the ship that I was on, but it was not Chemung...I am sure. As I got to the bridge, I saw the destroyer, which we had hit amidship, float off an sink. We were mustered to abandon ship, on deck, because the bow of our ship had a gaping hole in it. The convoy went to England without us. Se we sat there all by ourselves, sitting ducks for the German uBoats if they were to come.

"We managed to get a crew down in the hold to batten off the front compartment and kept us afloat. They turned us around back toward Canada, and we limped at 5 knots back to port...not knowing if we would ever make it back. I think it took two nights to get back. We were met by some Canadian subchasers and we made it to Sydney on Cape Breton Island. For the first week, we were told not to tell anyone that we were in a convoy, for security reasons, and this may be where your story came from. We were trying to protect the passage, to England, of the convoy that went on without us. German spies and uBoats were a big problem. Three or four months later, we were shipped back to Halifax where we joined another convoy to England. We participated in D-Day at Juno beach. I shall never forget standing on the bow at midnight, watching the USS Ingraham float off and sink. If you wish to contact me, you may call my residence at 504-486-4658. I live in New Orleans, LA and am a retired minister. Sincerely, Bill Brown."

I did call Mr .Brown and we had a lively discusssion. Apparently he had not read my book closely or he would have realized that he had been on the SS Awatea. (Later, the SS Awatea was hit by a German bomb during the invasion of North Africa and sunk off Bougie in the Mediterranean on 11 November 1942.) Trooper (and now Reverend) Brown was most emphatic when speaking of the mechanical impact of the crash particularly with respect to his immediate surroundings and the shattering of glass. He had in our conversation and in his first e-mail made no mention of a spectacular flash. After I reminded him of the occurrence of a tremendous flash of light, he agreed that such a flash had probably occurred. He spoke of the difference of time of events between my record and his recollection but I attribute that to the possibility of our ship's clock (probably British double summer time, a six hour advance from Eastern Standard Time) being different from the time kept on the Awatea's clock. Edison was out of Boston and the convoy ships had earlier assembled in Halifax. I do not think this is a factor. Irrespective of Mr. Brown's initial failure to recall the name of the ship he was on, and the omission in his first account of the spectacular flash of light, he was graphic in his detail of the impact of a mechanical collision. The crux of his narration is that he identified the destroyer USS Ingraham as the one that he saw sink and that he had been within a few seconds at the base of a ladder of actually seeing the Awatea hit her.

Trooper Brown had not mentioned a flash of light, but had noted,"I saw the destroyer float off and sink." Ships take a little time to sink, even those as grievously wounded as Ingraham. Could a ship almost dead in the water and with her stern fully awash as was the Buck, be one that is sinking. Could not the Buck have been the destroyer that floated off, and could it not then, presumably, have sunk? If the fog swallows up a ship that is sinking by the stern, has she not presumably sunk, as Awatea moves off and the destroyer disappears, into the sea or into the fog? Awatea, as the observing ship also would have continued her motion on into the fog. Or did several minutes moment freeze in space and time enabling one to see a whole ship go under the water giving that characteristic updwelling of water right after sliding under? Tough questions that many experienced sailors have faced in describing specific events of the North Atlantic in WWII.

Certainly two U.S. destroyers were in deep trouble that night. Given the improbability of reading a destroyer's name on its stern under those dense fog conditions, the Buck and the Ingraham still had markedly different profiles. Mr. Brown identifies "Ingraham." The differences in profiles (the Buck was a one-stacker and the Ingraham a two stacker) have not been remarked upon and I would not expect that distinction to be noted since there has been no incident report of anyone seeing both destroyers together.

The USS Chemung and the USS Buck were separated by several miles when Edison came across the Chemung afire. The Awatea picked up no Ingraham survivors and this could square with Mr. Brown's recollections very likely because the Awatea's forward motion carried her on into the fog. But if he saw and if the Awatea crew saw the Ingraham sink would not the question of potential Ingraham survivors have come to the fore with respect to the Awatea. It is my assumption, as I review the matter, that based upon elimination, the USS Bristol, DD-453, which attended to the Buck had in all probability picked up the Ingraham survivors. The convoy went on, the Awatea did not pick up survivors, and the Buck was incapacitated. That leaves only the Bristol and my ship, the Edison, and Edison did not pick up survivors that night. It was Bristol that picked up Ingraham's survivors.

I asked Trooper. Brown during my phone conversation with him to address the matter once again and send me his reprise directly. He did in a 2nd e-mail dated 07/30/2000. I quote it verbatim below.

"New Orleans, LA July 2000.

"I have read with great interest the fourth chapter of Captain Frank Dailey's book, "Joining The War At Sea 1939-1945." It whetted and enlightened for me the events of that devastating accident in the North Atlantic, August 22, 1942. I was a member of the Canadian armed services, having first completed two years of training, and now being sent to England in preparation for the European invasion.

On the night of Aug 22nd I was assigned to sentry duty on the forward deck of our transport the passenger liner Awatea. Our quarters were quite crowded, and we slept in rows of hammocks on the lower decks. As my partner and I dressed out for our midnight watch we were just beginning our ascent of the stairs when what we thought was a torpedo shattered every breakable thing in sight. Men were dumped out of their hammocks en masse and we discovered that we had collided with a US destroyer which was floating off in the patchy fog. Our vision was, of course, not perfect and our frantic concerns were for our own survival. However, our shared observation and analysis were that the destroyer sank within minutes accompanied by some rather loud explosions. It had always been our understanding that no one could have possibly survived. I was delighted to hear through Captain Dailey's research that there were eleven who did. "

"The Awatea's crew and some of our own men were able to batten off our damaged bow and keep us afloat, but we were alone in very dangerous waters. Our ship managed to return at about 5-6 knots to Sydney, N.S. on Cape Breton Island. We remained there for several months until another convoy shipped us out of Halifax to Great Britain.

William J. Brown."

Mr. Brown's statements are level and restrained. I attach much credibility to them. His certainty that Awatea had hit a destroyer that had then sunk, identifying it as the USS Ingraham, as expressed in his first e-mail, is a belief he apparently held for 58 years. At least a certaintly as to the fact of that ship sinking if not the name of the ship itself. There is a danger here that my reasoning, expressed in our telephone conversation, that Chemung's fire forward had convinced me that she had hit the Ingraham may have influenced Mr. Brown to change to "a U.S. destroyer" in his second e-mail as his identification instead of the "Ingraham." Destroyer distinctions are not under question here; a one stack Buck and a two stack Ingraham in a fog under emergency conditions would come out to be a "destroyer" to a Canadian trooper and I would be happy to have that man as a lookout on my ship.

It is now established as fact that the Chemung hit the Ingraham and the Awatea hit the Buck. The absence of a huge ball of fire in Mr. Brown's first e-mail, an illumination that would have put broken glass in an afterthought category, is persuasive to me tht his ship, the SS Awatea, is the one that tore into the stern of the USS Buck, DD-420, tearing off one screw, damaging the other screw, and putting Buck's after steering engine crew in peril. The fire in the Chemung's forward hold fits the explosion of the USS Ingraham DD-444 events, and the later rumble under the sea as her depth charges exploded as she went down. The distance from the Chemung to the Buck when Edison was standing by her as the two of us made our way back to the Buck tells me that those two did not collide.

The Awatea remaining close enough to Ingraham after collision would imply that Awatea had turned and come back. She would then very likely have put a boat in the water to rescue survivors or looked for some even if she felt that she were in precarious conditions. These conditions are not met in any version.

The two Canadian troopers on SS Awatea who have corresponded with me have since that event corroborated the fact that the Awatea turned back alone after their collision with the USS Buck DD-420..

Now, let me begin to relate information that correspondents who had fathers serving on the USS Chemung AO-30 on August 22, 1942 have provided to this website author in 2011 about events on the USS Chemung, and what their fathers related to them before their fathers passed. I will couple this with information from the Court of Inquiry that was held on the Chemung after the event, infrormation that was relayed to me some years earlier.

The USS Chemung AO-30 is key to much of the knowledge we have gained in subsequent years about the tragedies that occurred in Convoy AT-20 shortly before midnight on August 22, 1942. Here she is as she was rigged in those Atlantic convoy days. Chemung, unlike warships like destroyers and cruisers, which are either sunk in battle or become outmoded in time, lived on to have active naval service for many years.

USS Chemung AO-30, photo courtesy of Brian Rice on Sept 20, 2011. His father, Thomas Rice, was a Gunner's Mate serving on the USS Chemung, AO-30, during a night fog August 22, 1942 less than a day out of Halifax NS, a night that brought tragedy to troop Convoy AT-20.

Author and eyewitness, Franklyn E. Dailey Jr. whose destroyer the USS Edison DD-439 participated in the recovery aftermath of Convoy AT-20,, first wrote about the collisions in the original web version of "Joining The War At Sea 1939-1945." His original comments on these collision events are found in Chapter 4 of the 457-page published book, now in its Fourth Edition January 2009.

Survivor stories on the losses in Convoy AT-20 on August 22, 1942, received as recently as September 20, 2011, can be found in No Abandon Ship for Ingraham. That page is the next page in this series, or just use the link. It contains more details on the Convoy AT-20 event , brought to life by Anne Marie (McLaughlin) Harris and by Brian Rice, whose fathers were serving on the USS Chemung on August 22, 1942.

{RIP The first man ever to respond to my writings in these web pages in 1997, Orlando Angelini, whose USS Mayo DD-422 reunion I attended in 1999, has passed. . Bon Voyage, "Big Ange" Angelini.}

Rich Angelini is the grandson of the man we honored just above. Rich has had a busy Navy career, in which he has helped restore the destroyer, USS Joseph P. Kennedy, located near the USS Massachusetts, at Fall River, Massachusetts. These and other vessels at Fall River are maintained for visiting. Rich also assists in the care of the Museum of Navy artifacts on Massachusetts, from active World War II warships, that include the ship's bell, flags from the flagbag, and a torpedo gyro from my own ship the USS Edison DD-439.

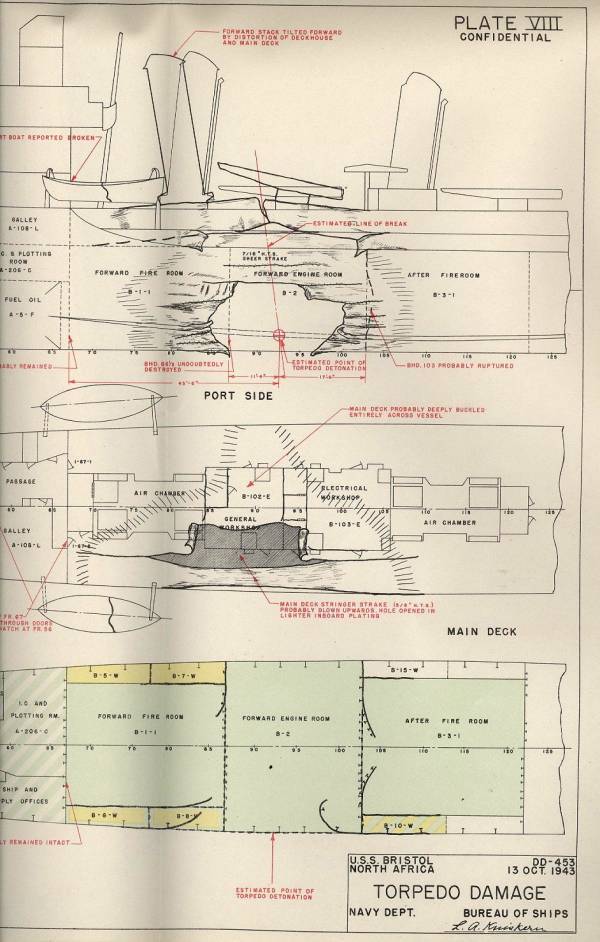

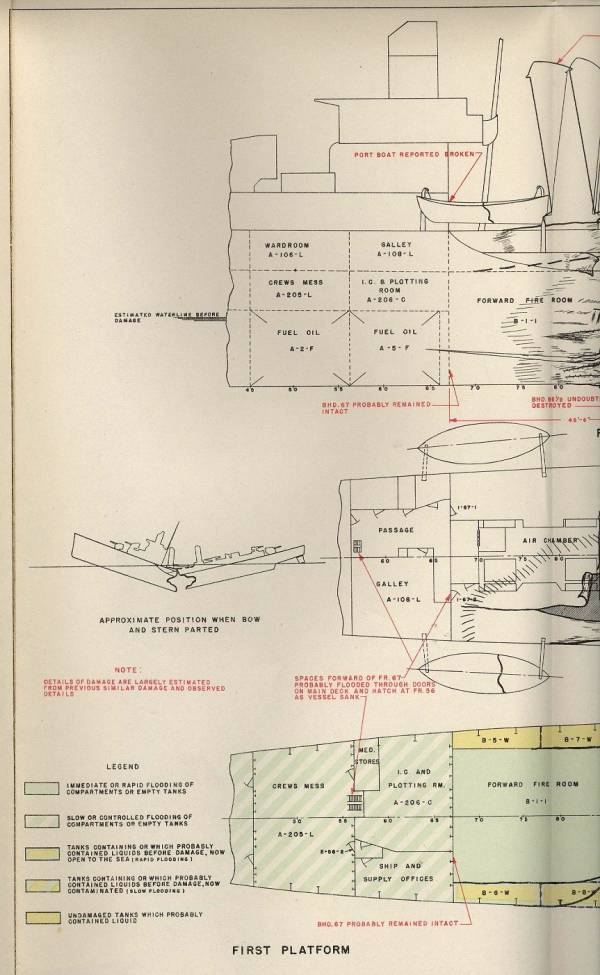

Rich Angelini has, on February 6, 2012, provided me with a Navy BuShips preliminary report on the sinking of the USS Bristol DD-453. I am privileged to present five .jpg files containing this report and will comment on what readers of this web page will see. In forwarding these images,. Rich commented: "The images of the Bristol sinking were sent to me by my friend Ed Zajkowski who owns the original war report that he saved off of a ship being scrapped in Philly." By "images" in this context, Rich meant the sketches that Buships made on the likely impact of the torpedo and its damage consequence, both made based on Bristol survivor's reports.

Readers of my book, "Joining the War at Sea 1939-1945," and/or of an earlier website page, seawar4.htm will know that Convoy AT-20, met fog one night out of Halifax in August 1942. Transport SS Awatea with 5,000 Canadian troopers aboard, clipped of f the stern of the USS Buck DD-420, the tanker USS Chemung AO-30 hit the destroyer USS Ingraham DD-444, which blew up an sank with just 11 survivors. The aftermath found this troop convoy, of such high priority that it had a battleship and a cruiser as Oceaan Escorts, sailing on toward Greenock, Scotland, with fewer screening destroyers. That is because my ship, the USS Edison DD-439 and the destroyer USS Bristol DD-453, were ordered to screen the damaged tanker Chemung, towing the propellorless USS Buck back to Halifax. The two screeing destroyers took more than a day to get their slow and partly disable 'convoy' back to Halifax when they were then ordered to prodeed at high speed to rejoin Convoy AT-20.

The prognosis for the ships in this 'mini convoy' also turned out to be poor. USS Buck, repaired and refurbished, was sunk by a U-boat off Salerno, which fired an acoustic homing torpedo right down Buck's throat, causing great loss of life. (See kendall.htm) The troopship Awatea was later sunk in the Mediterranean in convoy. The tanker Chemung later fought in the Pacific and had a great war record.

And the USS Bristol, our escort partner in the miniconvoy that foggy night off Halifax ,was later sunk while escorting a convoy in the Mediterranean. Again, it appears that an acoustic homing torpedo from a U-boat found its mark.

It is the Bristol's loss for which Rich Angelin has gorwarded the following five .jpg images that provide diagnoses based on survivor reports, including that of Bristol's Commanding Officer..

Page -44- is page one in the sequence here ./author/

page -45- is the second of two pages in which BuShips reconstructed the cause of sinking of USS Bristol DD-453 while that destroyer was convoying in the Mediterranean in WW II.

Before we get to two sketches reconstructing the point of impact of the torpedo and the immediate damage effect which led to rapid sinking of Bristol, it would have been interesting to find out if Bristol had her FXR (we called it 'foxer') streamed. This defense against acoustic homing torpedoes involved streaming behind the destroyer, a line that towed two parallel bars, Movement of the bars through the water caused them to vibrate, setting up a high pitched sound wave in the water. The idea is that this would attract the homing torpedo more than the screws of the ship. Once this capability was made available by the think tanks ashore in the U.S., Edison used the scheme constantly and our ship was considered not ready for sea unless the rig was working. I have seen torpedoes explode way back in the wake of our ship.

Author Commentary: I might note here that the USS Buck, DD-420, was sunk by an acoustic homing U-boat torpedo, and we know this because the U-boat skipper came to the U.S. after the war and lectured. But in that case, the U-boat was being pursued by the Buck, which had an active sound contact. The U-boat fired from her stern tube at a directly oncoming target and so the screw noise of the Buck was aft of Buck's hull, on zero azimuth, and the torpedo encountered the Buck's hull, first, and likely was detonated by a magnetic exploder or on contact with the Buck's hull. Finally, of the five ships involved in picking up the pieces left by Convoy AT-20 on an August night in 1942, SS Awatea, USS Buck, and USS Bristol did not survive the war. The only two of that rescue group to survive were the tanker USS Chemung AO-30 and my ship the USS Edison DD-439. Now, back to the sketches based on survivor accounts of the sinking of the USS Bristol DD-453. These are re-creations and they seem entirely credible to me. /Frank Dailey Jr./

Next, the first of two sketches where BuShips experts attempted to recreate the point at which a torpedo hit and sank the USS Bristol DD-453 while that destroyer was on convoy duty in the Mediterranean in WWII. My Naval Academy classmate "Whitey" McCain was an officer on the Bristol when she was hit and he survived.

Now, the second of two sketches of presumed damage to USS Bristol DD-453 that sank her while she was on convoy duty in the Mediterranean in World War II. This is the fifth and final image in this series.

Readers are invited to comment. It is rare to find such a battle after-ssessment. Contact author.

Home | Joining The War At Sea | Triumph of Instrument Flight