-------

.

Read The Triumph of Instrument Flight

- Navy Aerial Reconnaissance

- Warships at Morocco-1942

- Aircraft Carriers for Torch

- Battle for Morocco

- Bridging World Wars

- Supply and Support

- Husky, Palermo, Messina

- Bloody Salerno

- Luftwaffe Standoff Weapons

- Aircraft of World War II-"friendlies"

- Long "slog" at Anzio

- USS West Point AP23 War Cruise-part 1

- USS West Point AP23 War Cruise-part 2

- Singapore, Fateful Stop on "Joan's Journey"

- Update West Point

- Part I, Briggs on Casablanca, Sicily

- Part II, Briggs on Anzio

HMS Prince of Wales & HMS Repulse sunk off Malaya. War widow flees Singapore on USS West Point(AP-23) ex SS America. Remembered here in "Joan's Journey"

Baby Wee Choong Seng, age 1, with her Singapore Naval Base father, and her mother, also board West Point, which takes them to Bombay

Copyright 2013

Ships and Aircraft of World War II

This 'picwar' folder that you have found on this website features "Ships and Aircraft" that fought in World War II. Emphasis: warfighting, using pictures as the primary communication tool. There are many more to come from the U.S. Navy's Recognition Slide Set from World War II , 600 slides in all. The principal text offering in this page is "Joan's Journey." It begins a few paragraphs below.

Beginning with page picwar12, and continuing in picwar13, and picwar14, we return to storytelling, with transport ships and escorting warships, moving both military personnel and almost helpless humans caught in fast changing events of the early days of World War II.

The first leg of the first war cruise of the transport, USS West Point (AP-23), from Halifax NS to Capetown SA, was covered in picwar12.htm West Point AP-23 (SS America) in convoy WS-12X; HMS Dorsetshire takes convoy duty at Capetown is its title.

The final legs of West Point's first war cruise were covered in picwar13.htm USS West Point AP-23 (SS America) sails WW II seas; Halifax, Bombay, Singapore, Batavia, Ceylon, Basra

A drama that began while West Point and other transports were under Japanese air attacks at Keppel Harbor, Singapore, is told here in picwar14.htm Prince of Wales and Repulse sunk off Malaya; War widow leaves Singapore on USS West Point (AP-23) ex SS America This story, titled "Joan's Journey," begins below. Its author is Henry Reid.

Background: The WS series of convoys were known as "Winston Specials." Over 20 in number in 1941, and organized during the U.S. prewar 'neutrality period,' with Britain already fully engaged in war against Germany, these mostly Atlantic originating convoys were Britain's lifeline to her colonies, many of which would normally have been served by ships transiting the Suez Canal. With that avenue blocked by German/Italian dominance of the Mediterranean, routings took the long southern route, to Capetown, then north again in the Indian ocean to reach countries like India and Egypt. WS-12X involved a heavy troop component, and did not originate in England (though its troop component did) but at Halifax NS. Entering the Indian Ocean, now as a redesignated convoy, U.S. transports West Point and Wakefield, carrying British Territorial troops, were redirected, while enroute, by the Admiralty from Basra, as their destination, to Singapore, via Bombay.

Those British Territorial troops aboard West Point and Wakefield, numbering over 10,000, disembarked at Singapore, just as the peak of the Japanese thrust to take the island was being mounted. The change in original troop destination orders, was a reaction to the Japanese thrust south, coterminous with their successful attacks on Pearl Harbor and landings in the Philippines. Singapore is revealed to be so large in Britsh thinking that the leadership (Churchill, Gen. Wavell) was unable to consider cutting its losses, but in fact was compounding them.

A Foreword for "Joan's Journey"

This story was added in March, 2010, to bring to readers a poignant World War II story entitled "Joan's Journey," The story was researched and written by Joan's son, Henry Reid. Joan's Journey connects with the first war cruise of the USS West Point, just as that ship prepares to 'cast off all lines,' departing Keppel Harbor, Singapore, under that harbor's increased rain of Japanese air attacks at evening twilight on January 30, 1942. While Winston Churchill and General Wavell were compounding theier losses, read how Joan was cutting her losses.

John Dion's story of the first war cruise of the USS West Point has brought many web readers to picwar12.htm and picwar13.htm From reading Quartermaster Dion's account of West Point's first war cruise, reader Henry Reid concluded that his mother, "Joan," almost certainly made her escape from Singapore on the USS West Point. Other ships left Singapore under the same threat of Japanese bombing attack in the same convoy, but only West Point had not been damaged in bombing attacks; that ship was also moored at the most likely passenger embarkation point, and is recorded in Dion's account taking aboard passengers endeavoring to escape the imminent land attack of the Japanese on Singapore.

The sea transit, common to Joan of "Joan's Journey," and to the USS West Point (AP-23), is a relatively short (30 some hours) passage from Singapore to Batavia, Java. But, what an effect that passsage made to so many lives! And what a life-enhancing event that was to Joan, and to author, Henry Reid.

Henry Reid 's account below of how Joan made her way back to England continues on from Batavia. Readers can pick up "Joan's Journey" here and stay with it until she returns to the land of her birth. The charts that Henry Reid provides help the reader understand why that passage from Singapore to Batavia was so crucial. John Dion's account of the passage of USS West Point up the Strait on her way in to Singapore ties in very vividly with Reid's account of the departure along the same passage. The reader can find in part II of John Dion's account, picwar13.htm , what happened to West Point after leaving Singapore and Batavia.

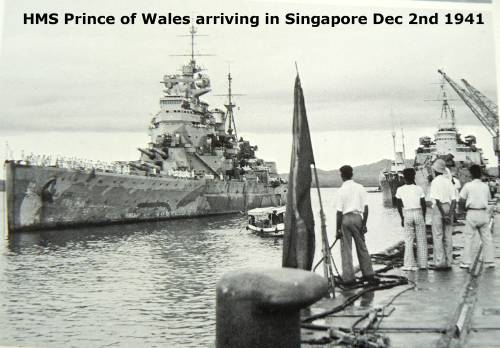

Henry Reid has permitted reproduction of his story here but retains all rights. The three photos below at the beginning of the story are, respectively, on left, Harry Reid and Joan's wedding in England, in center the HMS Prince of Wales entering Singapore on December 2, 1941, and right, LCdr Harry Reid, in the uniform he might have been wearing when he first went aboard Prince of Wales.

These forenotes by Franklyn E. Dailey Jr. March 23, 2010. Now, to "Joan's Journey," by her son, Henry Reid.

Joan's Journey

by Henry Reid, pictured here,

whose story begins here.........

Portrait of Joan by Count Mario Grixoni

Like many young people I failed to ask my mother (Joan, in the portrait above) enough about her past life before she died - she was only 55 and I was only 23 - and perhaps at that time I was more interested in my life than in hers. As a result I do not have as much detail about her escape from Singapore and voyage back to England as I would like, but I do have some recollections and I have a few letters, as well as the invaluable resources of the internet, so this is my best shot at her story.

My father Harry Reid was sent to the Royal Naval College, Dartmouth in April 1921 when he was aged 13½. One of his friends was one Derek Webber, my mother Joan's older brother, who invited him home one holiday, and so she and Harry met when she was just 12. Harry grew up personable and amusing, and as a young British naval officer in the 1920s and 30s, even if he did not exactly have 'a girl in every port' still seems to have managed to enjoy himself enormously as the Royal Navy 'showed the flag' around Europe and the Mediterranean. Joan was always on the fringe of his group of friends and nobody was terribly surprised that when Harry finally decided to settle down that it would be with her.

They were married in Fulham by the Bishop of London on June 2nd 1937. Harry's naval career had progressed well and he was at the time Flag-Lieutenant to Admiral Kennedy-Purvis, C-in-C of the British 1st Cruiser Squadron, based in the Mediterranean. After various other postings and the outbreak of war in 1939 he was aboard the cruiser HMS Manchester during the abortive landings in Norway in 1940 and met Vice-Admiral Sir Geoffrey Latham.

This officer was then posted to command the British Far East Fleet in Singapore, and invited Harry onto his personal staff. They sailed on civilian ships via Canada, Yokohama and Hong Kong, arriving in Singapore in early September 1940. Joan joined him in April 1941, having sailed from London via Cape Town. Harry, who specialised in 'signals' seems to have been extremely busy, and to pass the time during the day Joan got a civilian job with the Royal Navy as a cypher clerk.

In late 1941 the British Government decided to send a force of ships to Singapore as a 'deterrent' to the Japanese, and the brand new 44,000 ton battleship HMS Prince of Wales, the old WWI battle cruiser Repulse, and the new carrier Indomitable were despatched, along with some destroyers. Indomitable ran aground off Jamaica and was left behind for repairs but the other ships arrived in Singapore on December 2nd 1941, a Tuesday, under the command of the diminutive Admiral Sir Tom Phillips.

end page -2-

Harry, by now a Lieutenant Commander, was immediately transferred to the staff of this officer, and required to take a berth aboard Prince of Wales. He was busy all that week, but on Sunday, with the ship in dry dock having her bottom scraped after the long voyage from England, he was allowed home in the evening.

Knowing that war with the Japanese was now imminent, he took Joan out to dinner and dancing, probably to the famous Raffles Hotel. That night was to be their last together and, as Joan told me with some embarrassment when I was about fourteen, the result of it was me!

At midnight on that Sunday, 7th December in Singapore, eight time zones to the east, and the other side of the International Date Line, it was eight o'clock on Sunday morning in Hawaii and the attack on Pearl Harbour was just beginning, while meanwhile the Japanese had landed in force at Singora (in Siam but not far north of the border with Malaya) and at Khota Baru at the northern tip of Malaya.

The British Fleet at the Singapore naval base in the Johore Strait had no choice but to go out and attempt to forestall these landings even though they had no carrier to supply air cover and at 6.30 that evening the fleet rendezvoused outside the boom protecting the strait and sailed east and then north for Singora.

The story of the sinking of Prince of Wales and Repulse by Japanese 'Nell' & 'Betty' torpedo bombers on Wednesday December 10th 1941 is well known, and what happened to my father is covered in some detail in my story about his life, but suffice to say he was on the bridge of Prince of Wales with the Admiral and Captain of the ship until virtually the last moment and, although allowed to leave before these officers, did not survive as the ship rolled and sank.

The destroyers HMS Express, HMS Electra and HMAS Vampire picked up the survivors and sailed back to Singapore, arriving about 11 pm. Joan had intended to stay the night in Singapore town with friends, rather than be alone in the married officers' quarters at the base.

end page -3-

She wrote in a letter to her parents-in-law dated 20th June 1942 - after she had finally got back to England - 'I had the most horrible premonition from the moment I took Henry2 down to the ship on the Monday afternoon and all of Tuesday I felt terribly uneasy...I had gone into Singapore to stay the night...then I was rung up at 10.30...and went straight back to the base to wait for the destroyers to come in but had a terrible feeling Henry would not be among them.' She stayed for most of the night as the long trails of well and wounded walked or were stretchered off the ships. When there was no sign of Harry she knew straight away, she told me, that he was gone.

I believe that her brother Bobby was with her at the time but the comfort he could offer was perhaps limited, as he was not yet 21, thirteen years younger than Joan, and his ship, the Fiji class light cruiser HMS Mauritius, sailed the next evening for Colombo, according to one report on only one of her four engines3 and with her six inch guns inoperative, and apparently with Prince of Wales & Repulse survivors and some civilians on board.

Joan says in the same letter that Mauritius was sent out to the area of the battle off Kuantan to search for survivors but this seems unlikely in view of the ship's condition and is not supported by other accounts, which suggest that this task was in fact performed by the destroyer HMS Stronghold.

On the Sunday 14th, just four days after the loss of the ship, she wrote a short but brave letter to her parents-in-law in Scotland assuring them that their son had died quickly without 'being wounded or hurt' and that he had died 'for what he believed in.' She continued 'I don't have to tell you what a wonderful person he was, he had everything good in him and I am simply broken hearted at losing him. He did have a very happy life and our married life, brief though it was, was always happy'.

However Joan was not without support, as she had made tremendous friends with two girls who worked with her as civilian employees of the Navy. One of these was a girl called Joan Tanner whose husband Claude had been working as a civilian in Singapore but who had joined the RASC4 and the other seemingly a Joan (or possibly Jane) Howard (nee Cobb). At this stage, communications between Singapore and the UK were still in existence, although slow, and as the letter below makes clear she had sent telegrams to both her parents and parents-in-law.

Her father Tommy5 wrote to Granny6 on 22nd December 1941 in the formal way that people used in those days, as follows:-

2 Aka Harry 3 She had somehow managed to get salt water into her boilers 4 Royal Army Service Corps; Claude spent the war in Changi jail, but survived.

5 My grandfather Brig-Gen N W Webber CMG DSO 6 My grandmother Mary Reid nee Beaumont

end page -4-

'My dear Mrs Reid,

We sent Joan a night letter cable on Saturday (20th) which read as follows: "Cables received. Shandwyck (sic) replies all deeply grieving for you Reid stop Mummy paid fifty pounds account Esher Thinking of you always darling Webber"'. This rather curious joint telegram had been sent in this format to save expense. Even so Tommy suggested that he and Gaffy7 split the 12 shilling8 cost, and made the point that 'had I sent separate cables at ordinary rates, 1shilling and 3pence a word, it would cost both of us considerably more & in view of the long delay which now occurs the Post Office advised that nothing would be gained by sending at ordinary rates.'

Tommy was surprised to discover that it was now possible to send telegrams over the phone and have the cost charged to one's phone account, rather than having to go in to a Post Office. He continued by saying 'how very very sorry we are for you both - it was a terrible shock for all of us as so very unexpected'9 but his principal concern was obviously for Joan 'We can't bear the thought of her being shut up in Singapore and having to stand a siege in that climate - I'm sure Geoffrey Layton will do all he can to get her away while communications are still open.'

It is interesting to note that he envisaged a siege of Singapore, which implicitly could be withstood and eventually relieved, rather than the collapse that was shortly to occur. This seems to have been quite a common view at the time.

Notwithstanding Tommy's efforts, this and subsequent cables seem to have never reached Joan but he did receive one from her on January 19th, which had been sent on the 3rd: 'Please don't worry, am living 15 miles from Singapore & doing necessary war work. Will cable often - Bobby alright'. The significance of mentioning that she was living out of Singapore was to suggest that she was safe from the heavy bombing the town was now receiving. The reference to her brother Bobby was to let her parents know that his ship had recently been in Singapore which, with wartime secrecy, they would not otherwise have known.

7 My other grandfather Neville Reid (of Shandwick), hereinafter NR3 8 Equivalent to over $60 Australian in 2009 9 The family probably had no idea that Harry had gone to sea in the Prince of Wales, as his appointment in Singapore was a shore posting.

end page -5-

On receipt of this, Tommy, clearly seriously worried about his daughter, wrote off to Gaffy in Scotland 'Dear Reid,...We have cabled her twice begging her to leave before things get too bad but after yesterdays news of the Air Raids there my wife (Maudie) wrote to Sir Dudley Pound10 who is a personal friend & asked him to send a signal to the Admiral (Spooner) at Singapore, who is another personal friend, to have Joan evacuated at once - Pound's secretary telephoned this afternoon to say the message had been sent, so we are hoping now that she will get away alright... Yours N.W.Webber.'

As soon as the death of Admiral Sir Tom Phillips became known Admiral Layton was recalled from the liner on which he was about to sail from Singapore to replace Phillips as C-in-C Eastern Fleet. Layton moved his headquarters to Batavia11 on the 5th January and then on about January 16th to Colombo, leaving Rear-Admiral Spooner12 the Senior Naval Officer (SNO) in Singapore. (Ed.Note: The legend of Sir Geoffrey Layton's photo, next here, is at the bottom, in white.)

The first contemporary letter that I have from Joan is dated 11th January 1942, to her parents-in-law, and is written from 1 Changi Hill, Changi, c/o Major Boyle RE13 . With her husband missing presumed killed she had evidently been obliged to move out of the married officers' quarters at the naval base (which seems a bit harsh but probably reflects the pressure on accommodation caused by the convoys of reinforcements then arriving in Singapore) :-

'Dearest Mother and Dad,

I have had no communication from you or my family since November so suppose no telegrams are getting through at present. I have one wonderful thing to tell you, I am going to have a child so we will have something of Henry again and a lovely remembrance. I hope that this news will help to comfort you both a little...I have thought very carefully about what to do now and have decided to have the baby out here and these are the reasons.

First of all as regards safety. I am as comparatively safe here as I should be on the long sea voyage home or even in England where you may yet have to face an invasion. Secondly I am staying with a most charming young couple, he is a sapper, and we live about fifteen miles out of Singapore14 & have adequate air raid shelters etc. but they have said I can have the baby with them and the great advantages are that one can get very good nurses (baby amah) here who adore

10 1st Sea Lord i.e. Naval (as opposed to politiccal) head of the Royal Navy 11 Modern Jakarta, about 500 nautical miles south of Singapore 12 Poor Spooner finally escaped from Singapore in a Fairmile patrol boat with 44 others. Forced ashore on an uninhabited island, he and more than half the othersdied from disease and starvation. 13 Royal Engineers 14 Near where the International Airport is now located.

end page -6-

the children and take the greatest care also the clothing question is so much easier both for me and the child and such things as prams cots etc all to be had at very little cost.... There are very good maternity doctors and a very good hospital 15 and not very expensive....'

She was worried about money, as she and Harry had not had a joint bank account, so she could not access the £173 left in his account (which he had been putting aside for tax) and, although she was entitled to £300 as a result of his death and a £19/month pension from the Navy, neither of these had come through so far, although the naval paymaster had agreed to let her draw £20/month on account.

These concerns notwithstanding, at this stage she seemed very determined to stick it out in Singapore '...it is up to the white people to stay put and get on with their jobs, so far the morale of the Asiatics is pretty good, but the more white people who leave the more we lose face. I for one certainly don't feel inclined to run away at the first threatening of danger...I am as you know very strong and healthy and not at all afraid but you may be quite sure I will take the greatest care of myself now.

Henry & I were so very happy together that I can hardly bear to think of life without him but the child will I know comfort us, this is a dreadful time in the world but perhaps by the time he is grown up we shall have achieved a more peaceful & decent existence...'

She was desperate for the baby to be a boy and had chosen the names Adam Henry Nevile! I have no idea of the significance of Adam but the idea didn't survive the journey home. She still had her civilian job with the Navy but as the Japanese army advanced down the Malayan peninsula conditions and morale worsened. She told me years later that at about this time some of her friends advised her to have an abortion but she never for a moment contemplated it.

In response to Sir Dudley Pound's cable, passed on by Spooner, she had cabled back to her parents via the Admiralty 'Don't panic - Am determined to stay and carry on with war work.' This was phoned through by Pound's secretary on January 29th, presumably having been sent off a day or so before.

In Singapore, though, all had changed and that same day the decision was taken to abandon the naval base and to destroy as much of its equipment and stores as possible; the floating dock was sunk and the caissons and pumps of the graving dock blown up. All naval personnel except a skeleton staff were to be evacuated.

15 Only a month later the scene of terrible atrocities.

end page -7-

Joan told me that because she and her colleagues were civilians and 'up in the hills', no-one from the Navy remembered to tell them to leave until, according to a letter from Harry's older brother Nevile written to his parents just after she had got back to England, 'An officer came into the office and told them that they must leave at once'. I recall her saying something to the effect that 'we rushed down to the harbour and caught the last boat out.'

I think that by this time the Navy had commandeered the Singapore Country Club which is more or less in the centre of the island near the Pierce Reservoir and that her group were working there, so this is what she meant by 'up in the hills'. Because bombing and artillery fire across the Straits of Johore had made the naval base untenable, all shipping, civilian and naval, was now using Keppel Harbour, on the southern tip of Singapore Island's 'diamond'.(See map)

According to Nevile's letter 'she had no time to go back and pack, though the girl who was living with her brought two trunks full of Joan's things. These were put on an American troopship but at the last moment the girls were taken off & the luggage went on'.

It is impossible to be sure which ship she actually caught. However in a letter written by Tommy to NR3 on 7th February he says that he had received a cable from Joan sent from Batavia on Sunday night, i.e. the 1st February, which

end page -8-

said 'Arrived safely, got job' so whichever it was it had to be one that arrived before that. There seem to be three possibilities. Four large troopships carrying British reinforcements had come into harbour early on the morning of the 29th January. These were the Canadian Pacific liners Empress of Japan (30,000 tons and shortly to be renamed Empress of Scotland for obvious reasons) and Duchess of Bedford, and two converted American liners, the USS West Point (34,000 tons, formerly the SS America and seen here in her wartime camouflage) and the USS Wakefield, ex SS Manhattan. (Shown here, at anchor, is the West Point)

After offloading their troops and equipment all four ships were then co-opted into evacuating civilians and other non-combatants. Duchess of Bedford was damaged by bombs while in harbour, and although she did eventually get safely away she did not reach Batavia until 2nd February which rules her out. Wakefield, tied up behind West Point at the west wharf of Keppel Harbour was also bombed at 11.10 on the morning of the 30th January, killing five crew, and as Joan never mentioned that incident to me, I assume she was on one of the other two ships. I have a very faint memory that she once said it was an American ship so I am guessing that it must have been the West Point/America with her luggage perhaps ending up on the Wakefield/Manhattan, or vice versa. Either way all her possessions sailed away, perhaps to Colombo, never to be seen again.

Joan presumably made her way to the wharf by taxi 16. A good description of the scene that awaited her is given in 'Ralph's Story - Life in the British Royal Navy' by Ralph Robson who had been a signaller on Prince of Wales. 'The further we got into Singapore the worse the damage became... The widespread damage to houses shops and trees became more severe as we approached the docks.

At last we came to the quay which was jammed with every kind of vehicle and a seething mass of people. The congestion stretched in both directions from the dock gates' (Robson saw the liners lined up at the godowns and, showing much initiative, climbed aboard the West Point with two companions and persuaded the sentry at the top of the gangplank, and later the ship's captain Kelley, that they had been ordered on board because the ship needed someone who could read British Signals, which was in fact a complete fiction!)

Once aboard he was able to observe 'Although the ship was lying alongside for some time, very little was happening. This vessel could accommodate all the people on the dock but the wheels of bureaucracy were grinding very slowly.

16 There is no mention of Harry & Joan owning a car in Singapore. Those that did,and who escaped in this convoy, just abandoned them on the dock, according to John Dion (see next page).

end page -9-

Desperately anxious would-be passengers were filing past the entry point at a snail's pace. Each passport was being carefully scrutinised by English customs officers. Sometimes it took five or ten minutes to deal with one family. All the native people were refused entry to the ship. These were amahs, native people who had looked after white people's children. There were native Malays, Chinese and Indians amongst them. For long periods only one entry point was open. It seemed to be a complete shambles.

Another eye-witness, Ron Dodman, RE, also described the scene 'All that morning the docks and their approach roads had been heavily attacked by formations of Japanese bombers. Half of the big godowns in the docks were raging fires. The smell of burning rubber mingled with that of burning tar and rope....The quays, which were seething with women and children and their menfolk who had come to see them off, were so hot that one could feel the heat through the soles of shoes. Every inch behind the line of godowns and the ships was jammed with women and children waiting patiently for their turn to pass through the one small gate, where sat an official, one lonely man with a small card table and a pencil, who took down every passengers name, writing it beautifully but with painful slowness in a ledger.'

It seems that this tortuous bureaucratic process was suffered by those present in almost complete silence, broken only by the crying of amahs and children as they were forced to separate. Contemporary accounts do not countenance the idea that Europeans might also have been in tears but no doubt this was the case.

American sources seem to suggest that only the West Point and Wakefield eventually sailed in convoy, leaving just before 6pm on the 30th, but these two ships and Empress of Japan all arrived in Batavia on the same day, and I have established that they were in fact all in the same convoy, which was escorted by the light cruiser HMS Durban. Because of their deep draft the ships sailed due west to avoid the gaggle of islands immediately south of Singapore, and then turned south to run through the narrow Bangka Strait. The convoy moved fast, one account says 18kts, and was in the Roads off Tanjong Priok (the port for Batavia) around 3am on February 1st.

A number of American accounts say the ships arrived early on January 31st, having left Singapore on the 30th, but this is impossible having regard to the distance, and convoyweb.org.uk is clear that the following day is correct. I have also been in contact with Mr Franklyn Dailey, author of 'Joining the War at Sea' and he has referred back to his original source, a logbook kept by his friend Mr John Dion, (still alive at the time of writing) who was a quartermaster on West Point at the time and this confirms 1st February.

end page -10-

I remember asking Joan, in the light of the Japanese command of the air and sea, whether she had seen any enemy ships and she said that they had seen 'smoke on the horizon' at one point but otherwise nothing. In fact the weather was 'overcast and squally' which kept the Japanese bombers away and at this time, a fortnight before Singapore actually fell, it seems that there were not in fact any Japanese naval forces in this particular area. Some accounts mention the presence of submarines but it is not clear that these represented a direct threat and in any case the speed of the convoy would have made attack by submarine less likely.

All of the large converted liners were due to sail on to the relative safety of Colombo and beyond so one is bound to ask why Joan and her friends disembarked at Batavia? Lady Layton (who was the wife of the C-in-C, Eastern Fleet) wrote after she got home 'Joan...was so brave & so determined to stay on & do all she could to help the War - we hoped she might have come home with me, but she did not wish it.'

I don't for a moment doubt her commitment to her work but there was another pressing reason; she didn't have enough money for the fare. It had been a long standing arrangement that the War Office would pay the fares of the wives of Army officers wishing to follow their husbands to overseas postings, (called an 'indulgence') but the Admiralty expected the wives of Naval officers to fend for themselves. Joan's letter of January 11th says that the fare to South Africa was £100 (where she had thought of going) while it would be £24017 to get back to England. It seems probable that, as she was employed by the Navy, albeit as a civilian, the Navy was prepared to cover her evacuation as far as Batavia but no further. Clearly as soon as she got ashore, and notwithstanding the fact that it was a Sunday, she and presumably the other Joans presented themselves at the naval office and were promptly re-employed.

However, although not having the fare home, she was certainly not destitute or without contacts. Tommy's letter continues: 'A great friend of hers, a Dutchman now working in the Dutch Govt 18 office in London, has given us the names of two personal friends of his in Batavia & we have cabled the names to Joan so that she can get in touch with them.

17 The equivalent of over $20,000 Australian in 2009 on the basis of 1 pound Br = $A2 18 Java & Sumatra had been Dutch colonies for over three centuries with an expatriate Dutch population of over 500,000 in 1942.

end page -11-

She cabled her address as Hotel des Indes, which our Dutch friend says is the best hotel in Batavia, so she should be comfortable for the time being. Now we want to hear that she is on her way to S.Africa or Australia but I'm afraid she will try to stick it out in Batavia as long as there's work to do but it is pretty certain to be bombed before long -'

I think she was staying at this quite grand hotel (seen previous page at about this time) mainly because she couldn't find anywhere else due to the great influx of refugees from Singapore. Tommy was right about the bombing though. On 3rd February the airstrip at Surabaya, at the opposite end of Java where the Dutch naval base was located, was bombed and on 9th February Batavia itself was attacked. Intermittent bombing ensued, becoming fairly intense from about the 25th onward.

Frustratingly I can find no hard evidence of how long Joan stayed in Batavia or how she escaped (but see below). In a letter written on 4th April, when she was at sea on her way to New York, she refers to 'the really tough time - escapes, air raids, bombs etc that we had been through...' and later 'we had quite a perilous escape from there (Java) but I will tell you all when I see you.'

All British forces in Java including naval were in the joint ABDA (American British Dutch Australian) command under the overall direction of General Wavell. Until 12th February the American Admiral Hart had command of the joint naval forces and after that command passed to the Dutch Admiral Helfrich. The British/Australian division of naval forces was under the direct control of Commodore John Collins RAN19 (later Vice-Adm Sir John) who had been the (Ed. Note: see routing south from Singapore to Batavia, Java, via Bangka Straits)

19 As Captain of HMAS Sydney, Collins was a hero in Australia for his actions at the Battle of Cape Spada in 1940. He later became Australian Chief of Naval Staff and it is after him that Australia's Collins Class submarines are named.

end page -12-

Australian Naval Representative under Layton in Singapore and can be presumed to have known Joan personally and it was under the auspices of this officer that she and her companions were working. ABDA naval forces were much diminished on February 4th at the Battle of Makassar Strait and subsequent accidents and losses including at the Battle of Badung Strait (February 19th) greatly reduced ABDA's naval effectiveness. Finally at the Battle of the Java Sea (February 28th) and its aftermath ABDA naval forces were virtually wiped out by the Japanese Navy, losing 10 ships and over 2000 men. In any case, after General Percival surrendered in Singapore on 15th February, and due to the continuously deteriorating situation, ABDA was formally dissolved on the 25th February and General Wavell flew off to Colombo. The invasion of Java started in force on 1st March.

As mentioned above I can't tell whether Joan stayed through all of these disasters, although clearly her cypher skills would have been much in demand, but working backwards from the time she eventually left Sydney would seem to imply a departure from Java towards or at the end of this period. Many civilians and other personnel were evacuated by rail to the port of Tjilatjap, (see map20 previous page) about half way along the south coast of Java, and because she mentions escaping from 'Java' rather than from 'Batavia' I infer that this may be the route she took.

Commodore Collins is reported to have 'organised evacuations of civilian and military personnel to Australia and India' and he and his staff are known to have evacuated from Tjilatjap to Fremantle on March 2nd on the corvette HMAS Burnie. While it is possible that Joan was with them I think it is more likely that she left a day or two earlier on a civilian vessel, all of which had been ordered to leave port on March 1st.

Before writing this I had always thought that her route to Australia must have been Darwin-Sydney then by train to Melbourne, but this is clearly wrong. Darwin had been heavily bombed on 19th February and thereafter pretty much abandoned as a port. The nearest safe major Australian port from Tjilatjap was Fremantle, virtually due south, and all the ships that I have been able to identify as escaping from Java en route to Australia went that way. Most evacuees did not stay there but sailed on round the coast to Melbourne or Sydney.

However Joan's brother-in-law Nevile's letter (see page 8) says that she disembarked in Fremantle and then caught the train across to Melbourne. In 1942 the trains went three times a week and one was on the train for three nights, assuming no delays, which were common during the war. It was in some ways a tedious journey, because there were three changes of gauge, the first at Kalgoorlie, and again at Port Pirie, and as the Commonwealth Railway C class

20 Derived from Google Maps

end page -13-

locomotives needed water every 200 miles and coal every 600 miles, there were a lot of stops across the endless Nullarbor Plain. However if the girls had managed to afford the first class fare, the then considerable sum of £15/3/3, or - perhaps more likely - as refugees managed to get a free travel warrant, the carriages were air-conditioned, and there was a piano in the lounge. As the trains were often full of servicemen one may imagine that some of the sing-a-longs were on the risqué side!

In 1942 the Australian Navy, which was effectively under British control, was commanded from the Victoria Barracks in Melbourne and as Joan was still in the Navy's employ this was her obvious destination. I estimate that it would have taken about 6 or 7 days sailing to reach Fremantle from Tjilatjap and assuming a day or two in nearby Perth a further 4 to get to Melbourne, this would give her a possible arrival date in Melbourne of mid-March.

Her letter of 4th April when she was already at sea on her way across the Pacific says 'As you will know by now I am at last on my way home thanks mainly to Admiral Royle. When I eventually reached Melbourne I had decided to stay there & go on with the job and have the baby there but I soon realised that there were too many difficulties financial and otherwise. For one thing Melbourne is packed to overflowing already with evacuees, troops etc and is likely to become more so. It is very expensive & impossible to find anywhere to live or get a nurse or any kind of help at all as all the women prefer to make munitions for which they get an enormous wage, £6 per week! I then heard of a chance of getting back quickly so went to Admiral Royle who was more than kind and made it his personal concern that I and my two companions should be sent home via America at the Admiralty expense.'

Admiral Sir Guy Royle RN (seen below with the Australian General Blamey) was on secondment to the RAN as First Naval Member, Australian Commonwealth Naval Board, and Chief of Staff, which is the Australian equivalent of the British First Sea Lord. Judging by the way Joan refers to him it sounds as though he was another of Tommy's 'personal friends' which was perhaps why he approved the outlay of Admiralty funds to repatriate the trio!

Joan was very concerned about clothing as 'I have lost everything and it is no good arriving in England where the clothes rationing is so severe without something to put on as my coupons when I do get back will have to be used for the baby'. She had already collected a few baby things from 'from very kind people here, and also some wool & hope to get more in America as I imagine wool is very difficult to get hold of in England.'

end page -14-

Seemingly at fairly short notice the three girls were offered a berth on a ship sailing from Sydney so took the night train up from Melbourne. There were no sleepers available so they had to sit up all night and this was when Victoria still had the 5' 3" gauge track while NSW had the standard gauge of 4' 8½" so one had to change trains at Albury in the middle of the night21. What made matters worse for Joan was that she had carefully carried Harry's naval sword with her all the way from Singapore and while she was asleep someone stole it from the luggage rack above her head22. This soured her whole view of Australia; she wrote later '...I really dislike the Australians.' Of course Australia was a very different sort of society in 1942 and I daresay there was a lot of antagonism towards 'pommies' with posh accents because the debacle of Singapore, which had resulted in the death and particularly imprisonment of so many Australians, was seen as entirely the British authorities' fault. (And still is.)

On 28th March, after finding time to visit an English friend, Mrs Muirhead-Gould, wife of the (British) Commodore of the Sydney naval base, whose son, an eighteen year old midshipman, had been lost in the sinking of the Prince of Wales, Joan embarked on the converted P & O liner HMT Orcades (23,000 tons and seen here before the war).

Joan says that '....we are very comfortable luckily with plenty of room,' and Nevile's letter says they travelled first class. The ship, one of the first liners to be (partly) air-conditioned, was on her way to Halifax, Nova Scotia, to pick up a contingent of Canadian troops and take them across the Atlantic and may have been fairly empty on her long voyage across the Pacific. After calling in to New Zealand and to avoid submarines the ship went a long way south - Nevile says (jokingly) 'almost via the South Pole.'

The letter that Joan started on April 4th ends 'This is continued a fortnight later, still on the way but the end is in sight thank heavens - it has been a tiresome time and we have regrettably been ill with a kind of rheumatic flue, very painful, but all recovered now & longing to get off'. The handwriting in this section is a bit more scribbled and in a later letter she admits 'that by the end of that long sea trip we were all rather depressed.' Orcades23 passed through the Panama canal

21 The standard gauge line from Melbourne was not opened until 1962. 22 Neville's letter says it was on the run across from Perth but I clearly remember being told it was between Melbourne & Sydney. 23 Torpedoed and sunk by U-172 10 October 1942.

end page -15-

between 20th & 22nd April and then turned north for the long run up the coast of North America, arriving in Halifax about 2nd May.

The three girls immediately entrained for New York but, as I remember Joan telling me, somehow the US authorities had got wind that one of them was pregnant, which might have meant that they would be denied access. However although Joan was apparently not too obviously 'showing' by then, the immigration officer had somehow got it into his head that the culprit was Joan Tanner whose svelte figure and long separation from her husband convinced him that she was 'clean'!

As soon as they got to New York their lives started to pick up. The company that had employed Claude Tanner before the war maintained an apartment in the 'Graybar Building' 420 Lexington Avenue24 and they were allowed to use it 'which was very nice as we were quite independent....The month that I spent in New York did a lot of good...America was very exhilarating and I was really overwhelmed with the kindness & hospitality that I received. As I had lost all my clothes I arrived in New York with only about one garment that I could still get into, so we were sent to the English Speaking Union where we met a wonderful woman called Mrs Stewart and she gave me such lovely things for the baby and also clothes for myself and took us out to dinner & theatre & couldn't have been nicer, then some other friend sent me to a famous gynocologist (sic) who offered to look after me completely free of charge...'

After experiencing so many military and naval losses in the past few months she wrote '....it was very heartening in America to see all the immense amount of war material & troops that they are pouring out. I saw tanks & aeroplanes being loaded on to ships and was very cheered by this and by America's admiration for Britain and their eagerness to get going themselves'.

Because of her pregnancy the shipping companies were reluctant to take her across the Atlantic but she was determined to get home and not have her baby in America as 'the child would have been an American, which might have made things a bit complicated later. As the British consul said it might disqualify him (the baby) for a scholarship for Eton which made me laugh rather as by that time old Joe Stalin will probably be hobnobbing with the King in Buckingham Palace & Eton will be full of little comrades Puskin & Ivanovitchs!'

She wrote that she had obtained a letter from her gynaecologist and was

eventually allowed to take passage. What she told me is that at a New York

cocktail party she happened to run into the captain of the Dutch ship (the

Tegelberg, pictured), in which she had sailed from Capetown to Singapore

eighteen months before,

24 Built in 1927 it is still there and has recently been renovated.

end page -16-

and he arranged to get her on board. She sailed from New York in early June and arrived in Liverpool on the 16th. The Navy was still looking after her: 'When we arrived a Naval Sea Transport officer came on board and did everything for me - cushions & booking seats on the train etc which made things very easy'.

Finally back in her parents' house, Tudor House, Church Avenue, Farnborough, she wrote to her parents-in-law 'Dearest Mother & Dad. At long last I am really home, it seems quite extraordinary not to have to pack up & catch another boat or train!...I was so glad to hear your voices on the telephone'.

Waiting for her was a letter from the Admiralty saying that after waiting for the statutory six months Harry's death was formally confirmed, as well as a letter of condolence from Their Majesties at Buckingham Palace.25 Although she had never been in any doubt about it the Admiralty letter enabled her lawyer Mr Block to settle Harry's estate, little though there was, and for Joan to claim her entitlement under his life insurance policy. A further blessing was that her naval pension had finally started to come through.

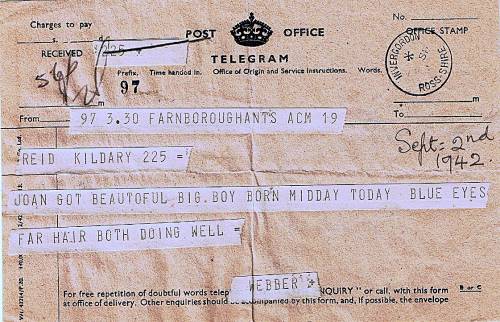

The next month was spent getting ready for the baby, interviewing nannies, scrounging cots & prams, and generally 'nesting'. She had intended to have the baby at home, partly because there was no room in the local hospital and partly because that's what most people did at that time. In the end I was born in Farnborough hospital and this telegram was delivered to my grandparents in Scotland later that day:

This, perhaps, is a good a place as any to end this story - the end of one life at the beginning, the start of another at the end.

Henry Reid, Bowral, NSW, Australia. 10th March 2009 adfit@bigpond.com

25 Originally held by me but lost when I moved house in about 1986

end page -17-

A short biographical note:

Joan Maud Caroline Emily Webber was born in East Kirkee, Poona, India on 23rd July 1910. (Now known as Khadki and Pune, respectively).

Her father was Captain Norman William (Tommy) Webber, Royal Engineers (b 22nd Feb 1881) and her mother Maud Frances Augusta Hume Critchley-Salmonson (b 2nd Feb 1882). Her parents were married on 26th April 1905 in the Cathedral at Gibraltar, where Tommy was serving with the 32nd Company RE. After returning to the UK he was posted to India in Sept 06, first to Ambala and later to Poona, and Maud sailed with him.

The family returned to the UK in 1911 and Tommy did two years at the Staff College, Camberley. During the war he served as a staff officer under French and Haig on the Western Front, gaining 9 Mentions in Despatches, the DSO in the Birthday Honours of 1916 and the CMG in 1918. He reached the rank of Brigadier-General and was BGGS to Lieutenant-General Sir Arthur Currie of the Canadian Corps in the period known as Canada's 'Hundred Days'. He was apparently known to the troops as 'Squib' Webber. Later he became 'Governing Director' of the Army & Navy Stores in London (see also my piece on his life).

I don't know where Joan went to school but she was presented at Court to King George V & Queen Mary on 14th May 1930. The invitation specified 'Court dress with feathers and trains.'

She married Lieut. Henry (Harry) Nevile Reid RN on 2nd June 1937. Their life together is covered in my story about Harry.

After the war she married Lord John (Jack) Raymond Bethell on 6th August 1948. They lived until 1960 at Cowden Hall, Horam, East Sussex where Jack had a small 'hobby' farm and later at Brookdene House, Graffham, West Sussex. They also had a flat at 48 Eaton Square, and later at 40 Hill St, Mayfair.

Jack was ill for a number of years and died on 30th September 1965. Joan, worn down by the strain of caring for him, and suffering from emphysema and an undiagnosed faulty heart valve, died on 22nd April 1966 in St Richards Hospital, Chichester. (End of Henry Reid's post note)

On June 7, 2011, we begin the story of a Singapore family fleeing Singapore on the USS West Point, which departed with USS Wakefield and the Empress of Japan, escorted by HMS Durban, about 6 p.m. local Singapore time on January 30, 1942, making it to Batavia on Feb. 1, 1942. (Note: This family stayed aboard West Point to Bombay. From an e-mail received 6/6/2011 dtd 4:48:51 a.m.)

"Hi

My name is Wee Choong Seng from Singapore. I was onboard the USS West Point when she left Singapore in Feb 1942. My father, Wee Yong Thye, and my mother Lim Swan Eng and I were onboard when West Point sailed and eventually arrived in Colombo. I was 1 year 6 months old then. DOB 1st Sept 1940.

My parents have since passed on. My father was working in the Naval Base in Singapore when the Japanese bombed the naval base. I think he was in charge of charging submarine batteries. I have an iron emblem of the submarine Loch Glendu with me, but I cannot find a record of this submarine.

After Colombo, we were transported to the Bombay Naval Base and we were in India for 4/5 years, and finally came back to Singapore in 1946 after the end of the war.

I have tried to access the passenger list onboard West Point when she left Singapore in 1942, but unable to find it. Again, I also tried to find the addresses where we lodged in Colombo and Bombay but could not find any clues on the internet. All I can remember is that we stayed at a house next to a canal and a jam factory and that I attended a school in Bombay.

I hope you can give advice as to how I can access the passenger list way back in 1942 onboard the West Point, and also records of my father's addresses in Colombo and Bombay when he as working as a naval base personnel there. I have tried to write to the archives department in India 2/3 years ago, but have not received any response.

Best wishes, Wee Choong Seng. Singapore " (Note: On June 7, 2011, a second e-mail from Wee Chong Seng0

"Hi

Most certainly you have my permission to publish my letter coz there may be other members of the Singapore Naval Base personnel who might remember this saga in 1942. I know that during the journey of West Point, two other British ships were attacked and sunk by the Japanese planes - one lies in the Eastern Anchorage of the Singapore harbour and the other one is near the Sultan Shoal lighthouse.

As for the emblems, actually there were two of them, the other one is with my brother who was born in Ceylon. I shall contact my brother and have photos taken and sent by email to you asap. Meanwhile, on the way home from India I remember we were attacked by kamikaze planes and our ship suffered bomb damages, but still sailed on and reached Singapore. My father was reinstated to work in the Singapore Naval Base, and was still doing recharging of sub batteries. He was given a Long Service medal for his services and retired in the early sixties.

I remembered I enquired at the British embassy in Singapore, for records of the naval base personnel in Singapore but was told that all records were handed over to Singapore in 1970. The only available source that I can make checks would be the Singapore National Archives, which I still have not done so. However, I am much more interested in our experiences in Ceylon and India, but this would entail searching records there.

Thanks for your reply. Best regards Wee Choong Seng"

Note: For those who interrupted the first war cruise of the USS West Point, this link USS West Point AP-23 (SS America) sails WW II seas; Halifax, Bombay, Singapore, Batavia, Ceylon, Basra will take you back to part II of that story as the ships are leaving Capetown SA, right after Pearl Harbor. You will have to scroll down to West Point's departure from Singapore on January 30, 1942.

end page -18-