- Chapter One - An Incorporated Village

- Chapter Two - Prelude to School

- Chapter Three - A Church Is Built

- Chapter Four - I Meet Sister Lucida

- Chapter Five - The Raleighs

- Chapter Six - Sister Emma

- Chapter Seven - Patriotism and Sister Florentia

- Chapter Eight - Fifth Grade Turning Points

- Chapter Nine - Seven, Eight and You're Out

- Chapter Ten - Epilogue

Fifth Grade: Boy Busineses used now-forbidden open jaw traps.

A skunk is trapped, subdued. All black pelt worth a dollar. Boy sent home; aroma trouble.

Sense of smell vanishes for him but not for others

Copyright 2013 Franklyn E. Dailey Jr.

Et ne nos inducas in tentationem.

Sed libera nos a malo. Amen

And lead us not into tempation.

But deliver us from evil. Amen.

Our school was becoming very crowded. World War I baby boomers like myself filled every available seat. Fire drills came more frequently. The sisters were obviously concerned. No one used terms like "pupil/teacher ratio." The sisters took all students who applied. But the physical plant came under pressure. Exceeding sixty desks in a room meant narrowed aisles. I cannot recall any specific date in the fall of 1930 when I was in the fifth grade and Sister Florentia, the Principal, was now my teacher, that a search was announced to find candidates for skipping a grade. No one ever approached me directly but the effort to find candidates was not kept secret. I was already popping out answers in sixth grade oral recitations. I developed a reputation for being somewhat irrepressible. In the beginning, in frustration over a lack of answers she thought she had imparted to the sixth grade students, Sister did turn to the fifth grade side and see if there was a "volunteer." I loved to volunteer. Sometime during the year I was quietly re-assigned to a desk over with the sixth grade. I have a vague recollection that this was preceded by a "parent/teacher" conference.

From then on, at the School of the Nativity of the BVM, my classmates were recycled each year.

That fifth/sixth grade year was not all roses. With Frederick "Buddy" Knight, who lived over on Fair Street that paralleled and was next to South Avenue, I had developed a trap line. Yes, those open jaw traps banned today. We prospected for muskrats (sometimes in our jargon, mushrats) and skunks. Despite the depression, there was a market for the pelts and Buddy's Dad knew where to sell them. Buddy had a .22 rifle in case we needed it to put an animal out of his or her misery. Sometimes we caught rabbits without intending to do so as their pelts had no value. Fortunately, Mrs. Knight could make great rabbit stew. Mostly, a rabbit would be gone when we got there early in the morning. They would chew their leg off at the joint above the trap jaw and leave it in the trap. One of our best places for a trap was under an old barn left abandoned when the new houses were built on South Avenue frontage in the late 19th century. One morning I discovered a pure black skunk in a trap we left in a foundation space leading under a barn floor.

Buddy was sick that morning and I was alone. No gun. Just me and a long piece of fallen tree that I wrestled loose from the undergrowth. It was about 5:30 a.m. on an early spring day. Frankie and his wooden club joined the fray against the skunk. That skunk fought like a tiger and dispensed clouds of perfume at every blow. I always knew the scent of a skunk but I had never seen it in fog form. I won, but the battle took an hour and it was getting close to school time. I retrieved my adversary and trudged home. Putting him in my hut in back of our barn, I got a quick breakfast and went to school.

We had just begun class when Sister Florentia called to me to come back into the cloak room . "Frank", she said, "I want you to go home and tell your mother to bury your clothes, give you a bath and get you back here as quickly as possible. "Why?" I asked Sister. "Frank, you are loaded with skunk fumes. The class will not be able to sit in the room with you and I know I can't."

So, as Sister directed, I went home, helped Mother bury my clothes, took a bath, dressed and returned to school. I guarantee to anyone, that if you have been on the battle line with a skunk, you will no longer be able to smell the stuff yourself. Buddy's Dad did sell the pelt. A perfectly black pelt, no white stripe at all, brought the trapper $1.00 in those depression days. That was a lot of money. It never dawned on me then that the buried clothes might have added up to more than one dollar. Money in the pocket was a countable item in the boy world. Buddy and I each had a 50-cent piece to show for our trap line efforts.

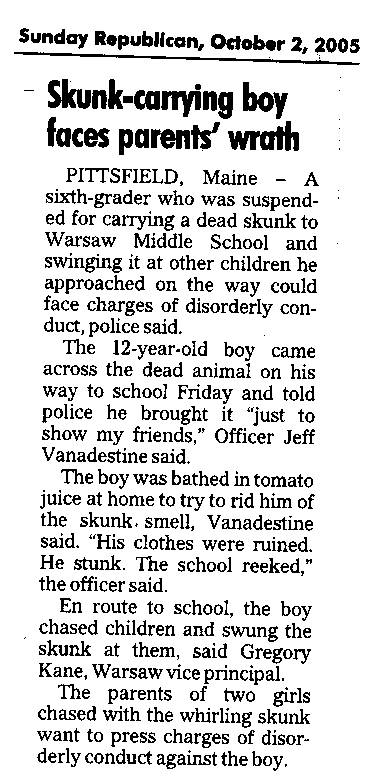

Here is a Pittsfield ,Maine, update in 2005 to the 1931 skunk story I related in the Sister's book. Sister did not call the police, as was done for the boy in the next news clip. Sister did not even tell the Pastor. If you read the Sister's book you will find out what Sister Florentia did when I came to school after my battle with a skunk.: No parents of my schoolmates pressed charges. Times have changed.

One feature of a pupil's life in the Nativity of the BVM school was the monthly visit of Father Krieg to every classroom to pass out the report cards for both classes. It was in Sister Florentia's fifth grade class that my memory of the event is most clearly etched. Father took Sister's place in her desk chair and she handed him the report cards, actually slim brown covered booklets with pages for each month of the school year. Each page was divided into subjects. The inside front cover page contained your name and some other essentials. All entries were made in beautiful Palmer Method writing by Sister herself.

Sister Florentia worked just as hard with those who might not excel as those who would do well. For this example, turn the statement around and it is just as true. To those who struggled, Sister contributed extra time at the Convent. Sister wanted the whole class to cross the finish line. In order to do this, she would work for weeks to get a slow learner from an F to a D. That was a triumph not only for the pupil but for Sister as well. And of course, it helped empty the classroom for the huge fourth grade coming up.

Father Krieg went by the book. His book. He never looked into the effort behind the result. The students with good marks received an "I expect this from every pupil." comment and the student with that D pulled up from an F would receive a lecture on how he or she was a disgrace to the student body. The student would take this rather hard. Rebukes, especially from the Pastor, had no redeeming value. Sister Florentia would just sigh and look to the heavens. I could tell that it tore her heart out.

Notwithstanding her erudition, it was in Sister Florentia's classroom I received the only erroneous information imparted by the Sisters in all my grade school days. In the sixth grade we took a course called, "Civics." It was a half-year course and I found it very interesting. During a now forgotten President's administration back around the turn of the 19th to the 20th century, possibly that of Grover Cleveland, Sister taught us, the "spoils system" had been abolished. Sister, I'm sorry, but someone sold you a bill of goods.

The Biblical admonition, "Sons, do not cleave to your Mothers'" came up for adoption by me about this time. It was not planned this way. In the absence for lengthy periods of a father and husband, I had been a partner with my mother in keeping a very large Victorian house functioning. For some time after he became insolvent, Dad was still the nominal owner of a coal business. Up to the point of total loss of the business, our basement would be filled each fall with about twenty tons of hard coal.

Blue Coal, a marketing name promoted by the coal arm of the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western (DL&W) Railway, was Pennsylvania hard coal with a blue dye sprayed onto it. It was a very long burning coal and was considered a good investment for heating if you could afford the cash investment to carry the inventory in your basement. It had fewer "emissions" than soft coal though it was considerably more expensive per ton. Dad's company carried Blue Coal, in several grades, as well as soft coal and coke. Another early advantage of Blue Coal is that it was advertised on radio by a creepy program featuring, "The Shadow."

It was my job to shovel coal into the mouth of our large, deep, double grate furnace. This furnace furnished the heat energy for a "hot water" heat system. It took all the strength I could muster to get that coal back onto the second grate. It was necessary before freshening the fire in the furnace, to use a long portable lever to rock the front and back grates to dislodge the clinkers and then a long handled steel rake to even the bed of fire. We banked at night to save fuel, letting house temperature go down while we sought heat under blankets. There was an opening to the furnace in a basement side room to remove clinkers that could not be dislodged from the front furnace door but it was necessary to let the fire go almost out to use this access. The final check on the furnace system was to check the sight gauge for level of water. Water was mandatory and it required manual intervention to open the valve. If the level was low, it was necessary to open a valve and raise the water to the required level, marked by a kind of rusty ring in the vertical glass sight gauge. Woe to me if I forgot to turn the water valve off. The radiators began spewing water that dealt the plaster in the ceilings an irreversible setback. All this background is intended to inform the reader that I was my Mother's partner for several years in keeping the house going during my Dad's periods of inebriation. I am proud of that partnership though Dad's binges made a somewhat fear -plagued person out of me.

One spring evening, a friend Edwin Davis, and I, decided to visit his Dad who worked as a night mechanic at Judge's Ford on Lake Avenue in Rochester. We set off on our bikes for the ride. The weather was good, clear skies with no moon, and we knew the way. Our bikes had no lights but that was no impediment to night biking in those days. South Main Street in Brockport connected with the "Million Dollar" Highway, Route 31, up at the "standpipe", a large vertical steel cylinder that held emergency water for the village. It was a marker of home for some and an eyesore to others. Here, Edwin and I turned east (left) and proceeded to Rochester via Spencerport, coming into the city on Lyell Avenue. At Lyell's intersection with Lake Avenue we turned south for a few blocks to Judge's Ford agency. We visited with Edwin's Dad for a few minutes, and courtesy of Mr. Davis had one of those peanut butter and cracker snacks found in early vending machines, and left to go home. It was now about ten in the evening. Since we were not quite as fresh as when we left Brockport , the trip home took a little longer. It was about a 19-mile trip each way and we got back to the standpipe a little after midnight. There had been only about two cars pass us on the way back. Fortunately, the standpipe stood on one of the Lake Ontario escarpments on the south side of Brockport so, for the return to the village, elevation was in our favor. Our bikes rolled down that Main Street hill pretty fast. I turned off at South Avenue and George went on to his home further into town. Thank God, no flats.

For the first time in my young memory, I was met at the door by a furious Mother. It was only about one or two a.m. In the beginning I simply could not figure out what she was so upset about. She really let the prodigal son have it. I listened respectfully for about fifteen minutes and without confessing error and with a steely feeling inside, I went to bed unrepentant. In retrospect, I had helped Mom by replacing the head of the house in uncountable ways. I felt I had contributed. I did not have enough depth of understanding to realize that Mother could actually be worried about me. I was, I guess, moving on, and my mother's own characteristic lack of emotion was one of the traits I inherited from her. I am not proud of the fact that I have had to learn the virtue of understanding from my wife but am glad she has been there to help. I hope I have moved on in this respect, too. This has been an uphill challenge for me.

My Times With the Sisters and Other Events, 134 pages, ISBN 0966625110; can be ordered through your local bookstore. Cover Price is $9.50.